Introduction

Organised firefighting on the Isle of Wight began with the launch of Ryde Fire Brigade in 1829. By the end of the Victorian period the island sported another five brigades at Newport, Cowes, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor. Additional non-local authority controlled firefighting units were available at specific locations. On occasion ad-hoc blends of an authority brigade and an external force combined at incidents.

The fire at Parkhurst Reformatory of 3rd August 1850 provides the earliest evidence of combined working at an IW fire. Newport’s 12-year old brigade responded with their crude manual engines and were joined by that of the military garrison, the prison staff and those of the Grubber brigade from the House of Industry. The report that appeared in the Illustrated London News refers to the courageous efforts of all but suggests no central point of command for the incident and hints at a free-for-all approach to the firefight.

An engraving of the Parkhurst fire as it appeared in the Illustrated London News. Note the presence of firemen with jets of water on the roofs of blocks adjacent to that on fire, and at bottom left the 400 youths that had evacuated the burning dormitory corralled in a field by armed soldiers of the Garrison.

Similar combinations were occasionally reported during the latter half of the century. Foundation of the Isle of Wight Fire Brigades Federation in 1894 formed the cornerstone of understanding and cross-boundary assistance for the following five decades. The Federation’s original aim was to raise the spectacle of organised firefighting through a series of annual drill competitions. In an age long before publication of nationally approved drill books, the agreements made between the island’s Chief Officers of brigades formed the basis of an understanding that was to benefit firemen, and those in peril, for many years to come.

As the interest in competition firefighting increased, firemen and their officers were compelled to engage in increasingly effective drill training. Skills and techniques were perfected to meet the standards required to complete drills without incurring penalty points and in the quickest time possible. Although the period 1894 to 1938 stands as a period of major firefighting evolution with island brigades engaging innovation at varying rates, the committee of the Federation, formed of officers and men of member brigades, ensured that all island firefighting shared common methods that were directly transferable to the fireground. This proved of inestimable value at large incidents requiring the assistance of one or more brigade from separate areas.

However, these skills and techniques were limited to the duties of a fireman – there was no theory or method for testing the command skills of officers at multi-brigade incidents.

On 22 March 1904 a major fire engulfed the first and second floors of Appley Towers near Ryde. The Towers’ in-house brigade formed by the resident Captain Hutt made a start on the task, but Ryde Fire Brigade were the first local authority brigade in attendance. Captain Sapsworth, officer in charge of RFB, aware of what was available elsewhere forged through the alliance of the Federation, called forth assistance from Sandown, Shanklin and Newport, which was readily despatched by horsepower. Following such a protracted incident from which lives were saved and a substantial conflagration engaged, one might assume that some form of debrief to include lessons learned would be headed by the Federation, but the minutes of the next meeting dated 7 May evidences no reference to the incident. One of those attending the incident was Chief Officer Nicholas Mursell of Newport Fire Brigade.

Mursell was one of the Newport volunteers recruited in New Year 1893 following the debacle of the paid firemen’s pay dispute in which they effectively sacked themselves by calling the Council’s bluff. Unconcerned the Council allowed the existing brigade to end their service as threatened and had already recruited twenty-one unpaid volunteers ready for training before the critical date.

Adhering to the pattern used successfully by Sandown Fire Brigade, the Council allowed the men of the reconstituted Newport brigade to vote for their own leader. Subsequently Percy Shepard was appointed as Captain, but he resigned in under two years. Mursell was appointed to replace him in New Year 1895.

Mursell’s reign was to be long and admired. He was a firm believer and advocate of the IWFBF. Despite his energy and enthusiasm, attempts to extract funding from his authority for the improvement of the brigade were continually thwarted. While the other principal Isle of Wight brigades steadily evolved through the adoption of new equipment such as respirators and steam fire engines, Newport’s men were left in the past. Even when Ventnor purchased the island’s first motorised engine in the early 1920’s, Newport were still using a horse drawn manually pumped appliance purchased in 1873 – they were the sole IW brigade to entirely skip the steam era.

Accordingly, by 1920 Captain Mursell faced challenges both politically and operationally that his Isle of Wight contemporaries had left behind before the First World War. In effect, he had learned to do a lot with a little and evidenced a substantial instinct for firefighting and commanding men.

Chief Officer Mursell and the men of Newport Fire Brigade, circa 1921.

Wadham's and the new age of fire command

A severe fire that began in the rear of Newport’s Wadham’s store in the evening of 4th October 1927 marked a momentous shift in the command of firefighting operations on the Isle of Wight, a shift marked by the astounding quick thinking of one Chief Officer which evidences remarkable similarities to modern methods of command.

In today’s fire service, commanding incidents involves a highly structured doctrine that is taught to all members of the service, firefighters and commanders alike. Across the 30 years of my own service the task of structuring the fireground, allocating tasks and responsibilities, accounting for safety, the resolution of objectives, supply of resources, and chain of command has developed significantly into what is known as the Incident Command System (ICS). ICS is a substantially revised and improved method. Like many significant evolutions the original concept of organised command was compelled by the extremes of war.

It is recognised and recorded in both official documents and popular histories that the efforts of the independent brigades and Auxiliary Fire Service during the early stages of the wartime bombing of Britain were courageous and admirable. It’s less commonly known that the methods of organising and commanding these disparate firefighting units was insufficient. This led, inevitably and appropriately, to the launch of the National Fire Service (NFS) in August 1941.

Creating the nation’s first and only nationalised fire service in a matter of a few months would have been an unthinkable undertaking in peacetime – in war it was a critical necessity. Among the many streams of work that NFS staff officers had to develop was the ability to communicate with and ensure that all firefighters and commanders from the Isle of Wight to the Orkney Islands were working to the same set of procedures. Of that necessity Operations and Training Notes were born (OT Notes were still the method of publishing procedural matters when I joined IWFRS in the mid-90’s).

Cap badge of the National Fire Service, 1941-1948.

The first OT Notes, based on the earliest experiences of wartime firefighting, were continually amended and updated throughout (and beyond) the conflict in response to lessons learned. An example with a local relevance was OT Note 9/1942, issued in July of that year, that comprised a reflection followed by recommendations of every aspect of commanding large incidents based on a handful of specific NFS operations including the Isle of Wight division during the Cowes blitz of two months earlier.

National Fire Service College at Saltdean.

Prior to the formation of the NFS, the Grand Ocean Hotel at Saltdean was requisitioned for Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS) purposes in 1939, just a year after the substantial complex had been opened for commercial business. Two months after launch of the NFS the facility was formally reopened by Home Secretary Herbert Morrison as the NFS College, although the NFS flag had been hoisted above the building and students had begun attending courses in the previous month. It was at Saltdean that NFS staff, under the leadership of Chief of Fire Staff Aylmer Firebrace, developed and delivered officer courses concerned with the command of incidents (among many other subjects).

But all this was unthinkable when members of Newport Victoria Sports Club spotted an orange glow through the rear windows of Unity Hall 14 years earlier.

Wadham's and fire

Deputy Captain Percy Wadham in later life.

Unlike comparable Isle of Wight business premises of the era, the Wadham's store in Newport's St James' Square was not prone to regular outbreaks of fire.

One record exists from September 1892 in which the carpentry shop at the rear of the premises was involved in fire at half-past-six in the evening. Fortunately persons remained on the property and were able to hail the brigade without delay. The response by Newport's on-call paid firemen was quick and effective. Political evolutions of the following few months evidence it was one of the last fires that the paid brigade were to attend (the story of why is revealed here).

Another effect of the fire, and of the politics of the borough fire brigade, was that Percy Wadham, son of Charles the proprietor of the store, volunteered to join the reconstituted brigade in February 1893. Later Percy was promoted to the rank of Deputy under Captain Mursell and remained in service until 1909.

No other reference exists to suggest any connection to Wadham's and the fire brigade.

Two days before the Wadham's fire, 2nd October 1927

The Saturday night shift of the Vectis Bus Company’s depot at Somerton were going about their duties as the clocked passed into Sunday morning. An increasing demand for public transport had compelled a rapid expansion of the company’s operations. At Somerton alone three adjacent garages housed 22 buses, and it was these machines that shift workers were employed to overhaul, repair where necessary, clean and refuel ready for the following day’s schedules.

A routinely observed task was the cleaning of the fuel tanks, and it was on one of these machines that this task was being carried out when a sheet of flame travelling rapidly on unseen petrol fumes swept across No.1 garage, the structure closest to the Newport road in which nine buses were accommodated. The workmen promptly responded to the fire call, and with patent extinguishers and buckets of water did their utmost, often at considerable personal danger on account of the large quantity of petrol about, to extinguish the flames. Their heroic efforts were of no avail, however, for the fire spread with extraordinary rapidity and fierceness, and in a very few minutes the garage was like a blazing furnace.

The flames reached such a height that the Medina was illuminated for miles around and the heat greatly handicapped the firefighting efforts. The bus workers backed off and turned their attention to moving the salvageable buses from harm’s way. Heat soon rendered this impossible from No. 1 garage and the men withdrew again, one collapsing into unconsciousness. The office where the telephone was located was torn apart in the conflagration. One of the men was despatched by car to fetch the brigade as a strong westerly breeze fanned the flames and loud reports were heard as fuel tanks and oil cans exploded in the heat.

Cowes Fire Brigade with their veteran Chief Officer Ernest Willsteed soon attended and expended all energies on saving the second and third garages. The task overwhelmed the town’s service and Willsteed sent for Newport who arrived rapidly in their two-year old Ford Stanley engine. By now firemen were driving and pushing buses from the remaining sheds. One was so hot that windows scorched and shattered as the struggling firemen pressed their aching shoulders against its rear.

Lack of water hampered efforts to suppress the conflagration. The hydrant on the main road was shipped but found insufficient. Two hundred yards away at Somerton Farm a substantial pond was identified. Hauling the Cowes steamer, comparably antiquated alongside Newport’s motor, was considered impossible over fields that resembled a bog. Newport’s Chief Officer Mursell ordered that his driver attempt the crossing in the motor. With narrow solid tyres it should have been impossible and a recipe for disaster, but somehow the determined driver kept his wheels moving, drew up adjacent to the pond and the plentiful water supply was achieved. By now the fire had done its worst but still the water was needed to cool and protect the substantial fuel tanks around the site that until then had maintained their integrity despite devastation all around. By five o’clock in the morning the fire was under control and as the first light crept over the horizon the scene in all its horrifying destruction was laid bare before the firemen and staff who wondered how they’d achieved what they had without serious injury during their two hour ordeal.

Isle of Wight County Press images of the devastation at Vectis Bus Company's Somerton depot. Credit - Alan Stroud.

In addition to the loss of 13 buses and the garages, other contents, including machinery, engines, tools, appliances, and stores of considerable value were destroyed. It was extremely fortunate that no one sustained any injury - reported the Isle of Wight County Press.

As dramatic as the incident was, its interest was lost in the smoke of a fire that occurred in Newport two days later.

The Wadham's fire, 4th October 1927

The St James’ Square premises of Messrs. Wadham and Sons comprised a substantial frontage of the market square’s retail facades and extended rearwards to a furniture workshop in a former tannery that backed close to the rear of Unity Hall. The substantial timber construction filled almost the entire void at the centre of the block of premises between the brick buildings, hidden from consumers by the structures that enveloped it on all sides. At the time the combined block of premises would probably have represented the most valuable and lucrative plot of retail estate in the town if not on the Island.

At 20:45 in the evening of Tuesday 4th October, members of the Newport Victoria Sports Club were holding a committee meeting in the back room of Unity Hall. Their discussions were silenced when members were distracted by an orange glow through the window blinds rapidly followed by sounds of crackling and snapping. One of their number, Mr P.E. Whiston, ran for the Police who activated the siren. By good fortune the members of the fire brigade had just returned from a civic procession for the service of hallowing the new Diocese at St Thomas’s Church.

Writing in his 1975 publication ‘The History of Newport Parish Church’, Wilfrid Way, who was among the congregation, remarked; The congregation filled the

Church, the Bishop was in his seat in the Sanctuary, the Mayor and Corporation and the Magistrates were in their seats in the Chancel together with the Town Clerk and other officials and behind them such members of the local Police Division as could be spared from duty. With them was the whole of the local Fire Brigade which, in those days, was an entirely voluntary part-time Borough organisation. Unknown to all but a few of the large congregation, a messenger came to the West Door and spoke to the Verger who, in his turn, whispered to one of the Churchwardens. The one who received the message, went quietly along the side aisle, noticed by only a few who were sufficiently inattentive, and whispered to the Captain of the Fire Brigade. It was very few of the congregation who did not see what happened next for the whole of the Fire Brigade filed out of the Church.

The ‘captain’ was Chief Officer Nicholas Henry Thomas Mursell, long standing landlord of The Castle, a fireman of some 34 years’ experience who was due to retire from the brigade (but not the public house) at the end of the year. Mursell directed his deputy, the notoriously tall Sydney Percy Scott, and others of his men to run the short distance to the station behind the arches of the Guildhall and bring the engine and equipment, while he and others approached the address indicated by the Churchwarden, Unity Hall.

In the darkened sky of the windless autumnal evening Mursell spied a pillar of smoke underpinned in orange stretching high over the roofs to his front. Newport’s Ford Stanley fire engine rounded into the square, its engine thumping, the driver weaving between members of the Sports Club gathered about the Hall they’d evacuated, waving, pointing and jabbering excitedly of smoke, of flames in the window, of crackling, and how they ran for their lives. Onlookers gathered, choking the firemen’s workspace, adding to the clamour while inside the Church the solemnity of the service continued.

Unable to extract useful information from the gabbling crowd, Mursell and his loyal and sturdy fireman William Phillips, accessed the building. In the absence of smoke, they pressed onward to the rear of the Hall. Suddenly, through the rear windows, a strong pulsating ball of orange revealed itself, Mursell and Phillips scooted back to St Thomas’ Square, knowing that the fire was not in the Hall, but in the space behind it.

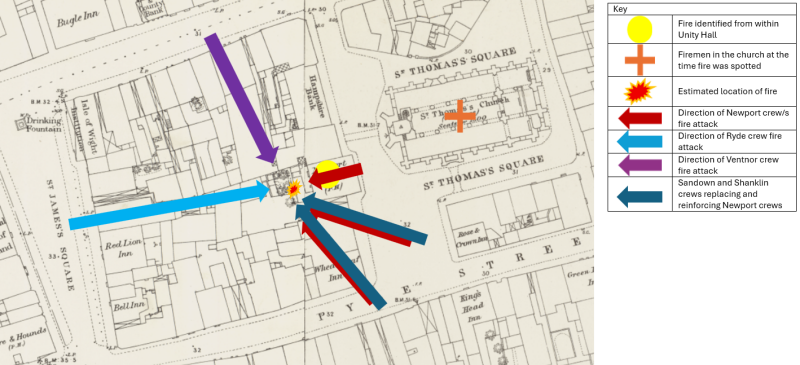

Mursell directed his fifteen men into a plan to surround and attack the flames. Two men were sent aloft to the roof of Mr George’s premises and directed a jet of water down into the space between the back of the Hall and the structure to its rear to prevent the fire from advancing. Two more jets were hauled through the St Thomas’s Square rear entrance of a workshop and a fourth was dragged by firemen in a desperate bid to access the yard to the rear of the Wheatsheaf Hotel while fleeing patrons clambered over the hose, tripping, cussing and getting in the way. The brigade’s Engineer, Fireman G. Lockyer, a motor mechanic of Mount Terrace on Snooks Hill who joined the brigade the previous February, set up the Ford Stanley and secured a hydrant supply.

The County Press expressed the opinion; For a time, it seemed hopeless to expect them to prevent the flames spreading to several adjoining premises, and realising the gravity of the situation the police telephoned for the assistance of the brigades from Ryde, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor. The Police made the call, but the request came from Chief Officer Mursell who quickly recognised the peril of the entire block of buildings.

The prestigious block of premises wrapped in the thoroughfares of St James' Square, St Thomas' Square, the High Street and Pyle Street.

By 21:30 the fire was said to have reached its zenith. Flames were pouring into the night sky an estimated fifty feet above the roofs of the surrounding buildings. Showers of embers were cast ominously to other properties on the cool breeze. Unity Hall posed the most threatened of the surrounding structures. A passageway of just a few feet in width separated it from the stricken workshop. Flames licked at and eventually shattered the rear windows of the Hall as Newport’s firemen risked life and lungs in the tight space to prevent the flames crossing the void. By now a horde of volunteers, including a local scout troop, worked furiously, in and out of the front of the Hall salvaging furniture, documents, records, and books of the Earl of Yarborough Lodge of Oddfellows which took up a peculiar appearance rearranged on the paving.

With the building clear of salvagers Mursell sent in more men, direct into Unity Hall from the front to use a diffuser branch to spray to push back the flames that licked hungrily through the now windowless frames as the roasting firemen in the rear passageway were struggling to suppress a torrent of combustion from communicating between the two structures. Other firemen forced an entry to Mr Arthur Wood’s premises and ran hose up the stairwell, through a window and on to the flat roof of an iron store to direct more water on what they could see of the pulsating beast below. To Mursell’s consternation and despite the gallant work of his men, no-one had clearly identified and been able to attack the seat of the fire. Its precise location remained unknown.

Mursell had the east and south sides covered by firefighting jets and the blaze appeared pinned but was not abating. His concern focussed on the seat of the fire; he considered it almost certainly somewhere amid the numerous timber framed workshops that extended from the rear of the robust retail frontages. The view available to the firemen on the roof resembled a dense shanty town of irregular inexpensive structures in juxtaposition to the gaily decorated well-presented shop fronts on all sides.

Ryde Fire Brigade were the first of the requested support to arrive, their gutsy Leyland FE Braidwood sounding their arrival with pomp and purpose. Chief Officer Henry Jolliffe conferred with Mursell who instructed him to proceed with his men and take up a position to the front of Wadham’s in St James’ Square. Mursell had a hunch and wished the Ryde firemen to force an entry into Wadham’s and proceed to the rear of the premises.

After entering via the storefront, the Ryde men discovered multiple points of access between the showrooms and blazing workshop. Separating the store from the workshop were heavy iron doors. Ryde’s firemen grappled through the smoke and selected one. With a heavy water spray in readiness, they forced the door and were staggered by the burst of heat and flame. Regaining their poise, they concentrated the water direct into the heart of the fire, staying low while inverted rivers of flame rolled across the underside of the ceiling above them.

Chief Officer Spencer and the Ventnor brigade arrived, also with a Leyland appliance, and Mursell positioned them in the High Street. Their objective was to make an entry through the International Stores, advance upstairs and provide a further jet working downwards into the mass. Chief Officer Mursell strolled anxiously about the block, reviewing his tactics. Three jets were now working from rooftops, a diffuser protecting Unity Hall internally, another jet in the International Stores, one in the Wheatsheaf yard, and Ryde’s hose was advancing inside Wadham’s itself. Three engines thundered at capacity to supply those at the front from the mains water network.

The three tenacious Newport firemen who had sustained continued heat punishment in the passage at the rear of the Hall experienced the worst when a large oil tank, located behind the Unity Hall passageway exploded, sending sheets of flame upwards and into the passage. All three were blown aside by the pressure of the discharge which fortunately blasted them out of the path of the flame front. They regained their feet, reset their thrashing branch, and continued the fight. Newport’s water supply was tested and wasn’t found wanting. Mursell was reassured as he conferred with each of his Island counterparts and returned to his original position at the entrance to St Thomas’s Church while the town’s centre reverberated to the beat of the pumps.

Shortly after Ventnor’s arrival Sandown and Shanklin’s appliances rolled into the square. By now the matter was gradually swinging in the favour of the firemen and those of the Bay afforded Mursell the capacity for fresh replacements for those exhausted, sweat ridden and blackened faces that staggered and spluttered from various posts.

An immense crowd had been drawn to the area like moths to the light and the Borough police had their hands full keeping them in check as they witnessed firemen stumbling out of the buildings. The police allowed and even encouraged a selection of robust young men to by-pass them and enter the Wadham’s show-rooms. Working behind the protection of the Ryde firemen’s water jets they resolutely hauled the stock of furniture out to the market square and stacked it neatly in the centre.

It took time, but with the fire surrounded on all sides the flames began to recede. To the onlookers the flames were lost behind the buildings as the unseen firemen pushed in from four sides, branches washing back and forth, extinguishing and cooling until in the manner of a victorious military pincer-movement they met in the middle, filthy and shattered, but safe and triumphant.

That the fire was unable to gain a hold of even one of the surrounding buildings is a testament to a job done with exceptional courage and skill. Even in today’s modern fire service with improved equipment and personal protection the author considers the reports of this fire to represent one of the Island’s optimum firefighting moments. The County Press correspondent who was there from its incipient stages remarked; The splendid manner in which the Newport firemen tackled an apparently hopeless task during the early stages of the outbreak brought forth expressions of admiration and appreciation of everyone. In view of the fierceness of the conflagration and the difficulties of reaching it they could hardly have had a more severe test, but they came through it with great credit.

The Aftermath

The aftermath of the Wadham's fire, photographed by the IW County Press from the tower of St Thomas', the morning after the fire.

Credit Alan Stroud.

Newport’s Borough Council next met on 12 October. The Mayor stated, I am sure it is the wish of the Council that I should express the towns thanks to the other Island authorities who allowed their brigades to respond to the call for help at the fire at Messrs. Wadham and Sons workshop.... they rendered valuable assistance and gave a feeling of security. As to the Newport Brigade, no praise was too high for them. As you know, I am a man of few words, so when I say this, I really mean it.

Alderman Wadham himself added; The Newport Brigade once more proved a very fine body of men and I am thankful that no-one was injured.

It’s ironic to note that by calling for the assistance of four other brigades, Newport had formalised no contract for work with Ryde, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor, in respect of the specification insisted upon by the Borough’s councillors and for which they had recently scrutinised and criticised the brigade. Perhaps it is coincidence, perhaps not, but the special committee comprising the Mayor and his hand-picked cohorts, who identified their own terms of reference when scrutinising the fire brigade and ripping up the rule book, suddenly disappeared from the agenda of future Corporation meetings.

Two weeks following the fire Newport’s firemen enjoyed a social gathering and dance at the Metropolitan Hall. Among the winning dancers were Fireman W. Phillips and Miss Hillyer who received their prize from the Mayoress Mrs W. Blake, who with the Mayor Mr W. Blake, and the donors of the prizes were thanked heartily by Deputy-Capt. S.P. Scott. The event also raised much needed brigade funds. The ferocity of the recent fire had destroyed various items of equipment including six lengths of hose and several firemen’s uniforms, emphasising the extremes they faced on that occasion. In December the membership of the Unity Hall, in gratitude to the members of the brigade, staged a whist drive to assist the firemen’s fund. Fireman W. Phillips featured again and emphasised the thanks of his colleagues to the Mayoress and the prize donors for their support.

Alas for Chief Officer Nicholas Henry Thomas Mursell, a fireman since 1893 and brigade commander since 1895, the pressure exerted by the council had already forced him to make the decision to resign aged 65. Over a 34 year commitment to the town, he had attended the worst and most trying of fires that struck the district, but that night in St Thomas’s Square he excelled. For the jovial and affable landlord of the Castle Inn it was quite simply his finest hour.

In Reflection

Command of the Wadham’s incident was notably the first of what today is a common course of events. Yet here for the first time in Isle of Wight firefighting multiple motorised fire engines responded from different destinations many miles apart and converged to weld as one fighting force in the battle against a rapidly developing enemy. The report written by the County Press correspondent unwittingly highlights many outstanding fire command features and, in the aftermath, much was made of lessons learned in the art of mutual assistance of motor pumps. For the first time in the Island’s firefighting history, it became apparent that assistance wasn’t just available, it was available rapidly! Had this incident occurred just a few years earlier, the response times from the East Wight coast brigades would have been drastically longer due to the need to obtain horses, harness them to a steam fire engine, and haul it for forty minutes to an hour in the direction of Newport. Timings suggested in the reports indicate that Mursell was swamped with multiple additional men and machines within twelve to twenty minutes of the asking.

No manual had been produced to dictate the formalities of rapid multiple brigade attendances; there was no Isle of Wight precedent set for such a fast moving and changing environment to which Chief Officer Mursell could refer. He simply had to make it up as he went along and at a pace that matched the rapid arrival of the assisting forces at his disposal. Interestingly, without any of the paraphernalia used to identify command individuals on today’s fireground, and without radio communications, the men of Ryde, Ventnor, Sandown and Shanklin didn’t need to trust to anything other than the organisation and leadership which Mursell provided. It was Mursell’s patch and therefore it was his command. He told them what his men were doing and what he wanted them to do, and they did it. The fact that his decisions were correct, and the men well led are down to the commander’s character and intuition, something that no manner of theoretical study can hope to emulate.

In the context of the Island’s firefighting evolution, the fire at Wadham’s was epic and highlighted the technological advance from horsepower to combustion engine and the command presence of one of the island's greatest Chief Officers, Nicholas Henry Thomas Mursell.