Since the creation of the Isle of Wight County Fire Brigade in April 1948, Newport Fire Station has been the centrepiece of the Island’s service. The South Street station in use today appears dated and bulging at the seams with far larger appliances and more equipment than it was designed to house, but it is a marked improvement on what went before.

The Fire Brigades Act of 1938 was the first piece of UK legislation that unambiguously compelled local authorities to establish and maintain a firefighting service by statute. Prior to that, Newport Fire Brigade, as one of the many independent services across the Island, found itself consistently behind its contemporaries across the Island, not by chance, but by the decision making of those in power at the Guildhall.

Newport Fire Brigade was formed in 1838, nine years after the Island’s first formal brigade was launched in Ryde. In this respect Newport were one of the front runners of Island firefighting, but that status wasn’t to last.

In his 1933 treatise The Law of the Fire Brigade, barrister Rowland Wynne Frazier attempted to unravel the complexity of the pre-1938 Acts or regulations that may apply to some local authorities. However provincial authorities such as those present on the Isle of Wight had no need to read any further than the first paragraph of the opening chapter – no local authority is legally compellable to maintain a fire brigade. That sentence and its ethos was sufficient for most local authorities to consider that anything they did commit to fire protection was, as Frazier phrased it, the voluntary system. If they chose to do nothing at all there was no recourse in law to affect it. Accordingly, the Island’s borough, town and parish brigades existed, were equipped, and paid (or not) at the whim of their local councillors. Studying the period 1830 to 1938 it becomes unavoidably apparent that Newport’s councillors were, in general, less inclined than their East Wight counterparts to prioritise time, funds and resources for firefighting. The result was a consistently less capable brigade.

Where the inaugural Newport Fire Brigade were accommodated is not known. It is known that 21-years after the Great Fire of London, Newport was in possession of a rudimentary wheeled manually operated fire engine. How the engine was funded and by who remains a mystery, but it was not uncommon after 1666 for a parish to obtain such an appliance, sometimes with financial assistance of a fire insurance office that had notable properties of value within the town.

The first engine was accommodated in the west end of the north aisle of St Thomas’s, according to the Ledger Book of Newport, 1567 - 1799. It was placed in the charge of the overseers of the poor, it being the case that the poor did the firefighting in an unorganised ad-hoc fashion when the need arose. That need arose in devastating proportion on 13 November 1785 when Newport suffered its own Great Fire. Seventeen buildings were razed to the ground, a further half-dozen badly damaged, and two lives were lost.

Prior to and after 1785, fire insurance offices, most notably the Sun and the Globe, made cash donations to the town to motivate their ongoing commitment to an elementary system of firefighting. There were no insurance brigades, there being too little business generated for the insurance offices to contemplate the substantial investment that led to insurance brigades in larger conurbations on the mainland.

Periodic donations were made into the early 19th century, each of them for a specified purpose, none of which relate to accommodation of the engine. Sadly, the records that contain the answers to those questions were among the numerous documents thrown into a skip for destruction when the Borough Council ceded to Medina Borough in 1974.

It is a fact that Newport’s fire station was, for an indeterminate period, within the ground floor of the Guildhall behind the arches on the west facing elevation. The earliest confirmed reference was located as an offhand remark in an Isle of Wight County Press article of 1893.

Throughout the Victorian era Newport’s Fire Brigade hadn’t been too badly off in comparison to its IW contemporaries. A fire report from 1852 suggests that the brigade, then in its 14th year, responded to a fire at a Pyle Street upholsterer with three engines. However, it should be considered that in the mid-19th century the term fire engine was as often used to describe a handheld fire squirt as a wheeled appliance. It is known for sure that a fine example of a Shand Mason manual fire engine was procured in 1874, the story can be read in full HERE.

As good as the engine was for its time, Newport’s firemen probably didn’t reckon on it still being in use as the Borough’s primary firefighting appliance until after the First World War. Unlike all the other established brigades in Cowes, East Cowes, Ryde, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor, Newport’s councillors refuted all attempts to obtain the cash needed to join the steam era. Newport’s firemen continued to manually pump firefighting water until finally catching up with the other brigades when they converted to the internal combustion engine in the mid-1920’s.

Long before that Newport’s brigade had gone through two major and acrimonious overhauls.

When the firemen staged a pay dispute in New Year 1893, they completely underestimated the position of the councillors by threatening to resign en-masse on 23 February unless their demands were met. The councillors, with three abstentions, voted to accept the notice of resignation and in a space of three weeks recruited a new voluntary (unpaid) brigade that were given ten days training in the hands of retired London fireman John Shaw.

On the evening of 23 February, the new volunteers of Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade, were formally appointed by the Mayor Sir Francis Pittis, J.P. before proceeding down the Guildhall stairs to begin their service. At the same time the embittered outgoing men of the paid brigade were arriving to handover their uniform and accoutrements. All gathered amid a tense atmosphere behind the arches. As fate would have it, at that very moment a fire occurred at a Pyle Street wool shop. Both brigades claimed the shout as their own, grabbing and snatching what kit they could obtain before fleeing to the west end of Pyle Street like a gaggle of quarrelling geese with both the incoming and outgoing captains in tow. The quarrel didn’t end there. Determined to enforce their domination in one last blaze of glory, the old hands barged into the smoke and re-emerged announcing the Stop. As they began to make up the gear, the Volunteers disagreed that the job was properly investigated, and a scuffle broke out over the equipment. It took the wisdom of captains Charles Osborne (outgoing) and Percy Shepard (incoming) to prevent the fracas escalating further.

Badge and button of the Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade, featuring the borough coat of arms. These continued in use after the reformation of the Volunteers into a paid service until the Fire Brigade was absorbed into the National Fire Service in August 1941.

N.H.T. Mursell

Within a year Percy Shepard stepped down. Nicholas Henry Thomas Mursell, the popular landlord of The Castle Inn (for a total 54 years) was handed the captaincy. Under Captain Mursell’s guidance the Volunteers twice won the coveted Battenburg Cup at Isle of Wight Fire Brigades Federation drill competitions (1897 and 1903). The latter victory was marred by the Church Parade held at Holy Trinity in Ryde, where parade master James Dore, the captain of Sandown Fire Brigade, called out black helmets to the rear, when forming up the massed brigades in Dover Street for the procession. The barbed reference was to Newport’s black leather helmets – all other Island brigades sported the brilliant brass version.

This being another example of Newport’s firemen being the poor-cousins of IW firefighting, Dore’s remarks lit the fuse, coupled to that of another unnamed officer who referred to Newport brigade as the black rooks. After twelve months of continuously badgering the Council, supported by letters published in the County Press, the firemen got their way and were supplied with the fetching Merryweather brass helmets.

In 1907, in possession of a new wheeled escape ladder, the brigade required more space. Arrangements were made to extend the capacity of the fire station by removal of a partition wall that remained from the years when the Guildhall’s ground floor was a marketplace.

The image above was taken of the IWFBF members that attended the annual drill competition held at Church Litten, 16 September 1897. The members of the Newport Fire Brigade that hosted the event can be clearly picked out due to their highly polished leather helmets appearing darker and reflecting the light differently to those wearing brass. Behind the man circled furthest to the left, the chap in the cap is Charles Langdon, the creator of the IWFBF, who had already resigned from Ryde Fire Brigade by then but remained secretary of the Federation.

Returning to the matter of Newport lacking a steam fire engine, this is all the more shocking given the events of 12 April 1908. The Jordan and Stanley store occupied an extensive footprint between Upper St James’s Street and what is today the bus station. On that Sunday morning the entire building was destroyed by fire. Newport’s firemen, equipped with the 1874 manual engine and a hose-reel cart (which was damaged when the frontage of the premises collapsed upon it) could do little about it with their puny devices.

A plea for assistance was despatched to Shanklin who possessed the latest in steam fire engine technology – the Merryweather Gem. With horses harnessed and the crew all up, Captain Oscar Rayner and the Shanklin firemen and machine arrived at Nodehill with boiler pressure-up and ready to protect the adjacent buildings within a time of 35 minutes, according to the County Press.

In the aftermath much was made of the impressive result of the Merryweather’s performance, this being the first occasion on the Island when steam power was used at a real fire. Newport’s Borough Council sent formal letters of appreciation to Shanklin, and the press was full of admiring reviews by those who witnessed the action. But still Newport’s councillors couldn’t be budged to invest in the technology.

Instead, they trawled for reasons to question the efficiency of their firemen, and when they had located sufficient justification, announced in early September that the Volunteer Fire Brigade was to be disbanded and replaced by a paid organisation.

The message contrived by the Council and published in the County Press, is worded in such a manner to suggest that the 15 year history of the Volunteers was little more than a temporary stop-gap – The town will forever be indebted to the Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade for stepping into the breach at a time of emergency and evidencing truest patriotism in the interest of the old borough and its inhabitants. The fact that members of the present Brigade are eligible for reappointment is sufficient assurance that this change means no reflection whatever on the men who for the last 15 years… have given their services for protection of life and property from fire.

The latter factor would have allayed any fears that the debacle of 1893 would be repeated. It also promised the Volunteers that their future efforts would be rewarded with tangible gain rather than patriotic rhetoric. However, nothing comes free.

The overriding reason for the Borough Council’s decision to reconstitute the brigade on lines of paid employment had nothing to do with generosity and everything to do with control. Council was convinced that 15 years of volunteering had empowered firemen to pay scant regard to discipline. The brigade was, in the view of councillors, rapidly descending into a maverick collection of barely controllable brass helmeted buccaneers. It was believed that if paid for their work, the Council could effectively demand, and maintain order.

Later the same year, as the plans to restart the brigade were finalised, the Volunteers went for their annual outing. Arriving at the Buddle Inn, the firemen, joined by several councillors and the Mayor, Mr A. Gill-Martin, QC, who expressed his hope that the men enjoyed their day out, reiterated that – whatever changes might take place I hope that all the voluntary firemen will rejoin the paid brigade. Captain Mursell raised a toast to the Mayor but didn’t miss the chance to pitch an appeal for a steam fire engine in his summary of the life of the Volunteer brigade.

Unnamed Newport fireman during one of the turn of the century IWFBF drill competitions.

Four weeks later in early October the Corporation published a 24-point set of rules that would apply to the new brigade (an original copy is held by Carisbrooke Castle Museum). The rules reveal that the brigade was to consist of Chief Officer, Second Officer (the use of ‘captain’ being removed) and 14 firemen numbered 1 to 14 in order of seniority. Movement between numbers 3 to 14 would remain by seniority, but vacancies for Second Officer or firemen number 1 and 2 positions would remain subject to a democratic vote. Chief Officer would no longer be chosen by the men and was to be appointed by resolution of the Corporation. Everyone would be compelled to resign on reaching the age of 50 with exceptions applied to officers in special circumstances. All members were expected to attend a monthly drill session for which all, except the Chief Officer, would receive 2 shillings per drill.

Any member wishing to resign was to give 14-days’ notice in writing. In the event of indiscipline, the Chief Officer was permitted to suspend any man but must then forward details to the General Purposes Committee for further investigation. Rule 9 stated that suspension would immediately apply to – Any member using improper language, or who may be found the worse for liquor, or guilty of practical joking, insubordination, or disorderly conduct at drills, fires, or assemblies on duty in the uniform of the Brigade. Any member intending to leave the district for a period exceeding 48-hours was to provide notice to the Chief Officer. Among the Second Officer’s responsibilities was that of Station Officer, in order to keep the station, engines, escape, and all equipment clean and prepared for immediate use, for which he would receive an additional £1 1s per annum. Pay rates for attending fires were specified, as were the charges to be levied on those calling the brigade, with a substantial additional cost for those outside the borough.

Two weeks later the IW County Press carried an advertisement for firemen vacancies. By then it had been confirmed that the changeover from Volunteer to paid brigade would be effective at midday on 24 November. On 6 November the General Purposes Committee revealed the names of the 14-firemen to be appointed.

Among them the following were from the pool of existing Volunteers.

- George Henry Appel, house decorator of 19 West Street.*

- Frederick Charles Appel, cycle mechanic of 10 West Street.*

- William James Fallick, baker of 18a New Street.

- John Francis Denham, of 2 Beech Road.

- Harry William Parnell, undertaker of 29 Hearn Street.

- William Phillips of 9 Clifford Street.

- Percy William Snellgrove, stoker of the Electric Light Co., of 28 Victoria Road.

- Edwin Hurry, iron founder of 11 Crocker Street.

*The Appel family name was originally Apple – it appears that this became unpopular around the turn of the century when Census entries favour Appel, sometimes with one ‘L’ sometimes with two.

The new firemen were as follows.

- Percy Scott of 46 Victoria Road.

- Roland Taylor of 9 Fairlee.

- F. Gentle, outfitters assistant of 27 High Street.

- John Matthews, carriers carter of 1 Chapel Street.

- Wilfred A. Morgan, carpenter of 18 Drill Hall Road.

- Sidney Percy Scott, builders foreman of Dainhurst, Mount Pleasant Road.

A week later the County Press carried a letter from Fireman G. Scott, formerly of the Volunteers who wrote – I should like to call your attention and that of the general public to the great injustice inflicted on myself and some of the members of the Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade in being refused admission to the newly constituted Fire Brigade. It becomes apparent that the desire stated by Councillors to entertain all the Volunteer’s as paid firemen were hollow words. Every man desiring to maintain membership was required to apply in the same fashion as those outside the organisation, with the impression given by repeated Council statements that the matter was an academic necessity and nothing more. Not only did Fireman Scott allude to undue influence being responsible for several of the Volunteers being discarded, but he also claimed that several of the proposed appointees do not comply with the new rules and regulations, without specifying in what manner. The matter was exacerbated by the publication of Councillor Salter’s words in the previous week’s edition of the CP – The Volunteer Brigade seems to be out of hand and manages their own affairs, we never hear from them until they want money spent on their appliances. This invoked Fireman Scott to ask – Is this the compliment we are to receive after so many years’ service…?

Although Scott implied that others of his ilk were affected, his public complaint was in isolation. Nothing came of it and the date of Tuesday 24 November approached rapidly.

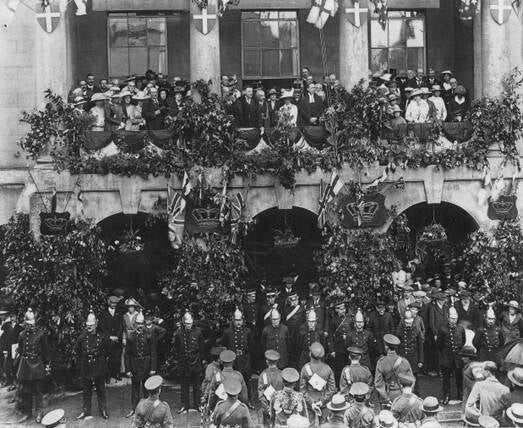

Newport's first 'proven' fire station, beyond the arches of the Guildhall (circa 1905).

Those who established the Volunteer Brigade in 1893, no doubt clearly recalled the debacle of the handover of equipment enflamed by a sudden fire call. As fate would have it, the very same thing happened at the Guildhall fire station at midday on 24 November 1908 – this time the call was to a shed, pigsty, and fowl-house fire in the garden of the Barley Mow. Fifteen years earlier Nicholas Henry Thomas Mursell was one of the scuffling volunteers attempting to wrestle equipment and initiative from the outgoing paid firemen. On the occasion of November 1908, Mursell’s officer role was to bridge the changeover, enabling him to diplomatically hand one last salute to the Volunteers, who rode with him to attack the fire in Shide, whilst ordering the new members of the paid brigade to wait discreetly on station for his return. They were to get their baptism by fire later the same day when a wooden structure used as a carpenter’s shop at the back of Chapel Street was enveloped in flames.

During the First World War, Newport suffered the same brigade manpower shortage experienced by all fire services across the country. When the first of the keen young men voluntarily signed up, in expectation of the war being a brief affair and home in time for Christmas, the matter wasn’t acute. By the end of 1915, and a second Christmas in the trenches of France and Belgium, the opposite was apparent, and the butchers bill was taking an unprecedented number of lives. In order to continually feed bodies to the frontline, the voluntary method was insufficient. This led to the Military Service Act of March 1916. All able bodied single men from the ages of 18 to 41 were liable for conscription, an amendment to the Act encompassed all married men and a later Act pushed the upper age limit to 51. Fire brigades were stripped of their greatest asset – their fit young firemen. Newport like their counterparts were affected by a manpower reduction of between 60% - 75%.

As early as February 1915 the Corporation had brought in measures to create a Fire Brigade Reserve, which when launched was titled the Newport Voluntary Honorary Fire Brigade. However, the main motivation behind the VHFB was not a perceived lack of firemen, it was to bolster the regular brigade in preparation for the expected aerial assaults from rudimentary bomber aircraft and the dreadful airships. Among the first to volunteer for the honorary reserve was former Deputy Captain Percy Wadham. Percy was only 35 when he resigned in 1909 to focus on his business and personal interests, but he was keen to re-engage in time of war.

Maintaining sufficient numbers of reliable men for turnout proved challenging. When the brigade was turned out to a major fire at New Barn Farm on the Swainston estate in April 1915, Captain Mursell had just six firemen at his disposal. Among them was William Fallick, who in the following month attended a ceremony to receive a 10-year long service medal from the National Fire Brigades Union – however his firefighting ended there as he was leaving three days later to join the 5th Hampshire’s at Southampton. The County Press reported that Fireman John (Jack) Francis Denham had recently left the brigade due to ill health, he too attended to receive an overdue 10-year medal.

Whatever the nature of his medical reason for leaving the brigade, the 41-year-old remained as CQMS of B Company, Isle of Wight Rifles, in which he’d served since 1908. He deployed with them aboard the Aquitania on 31 July 1915, was wounded in action and transferred to the Hampshire Labour Corps in 1916. The County Press report of the ceremony detailed that in addition to those about to depart for war service, six others had already joined the Army – Second Officer Alfred James Whittington (killed in action 12 August 1915), plus firemen William Phillips, Edwin Hurry, Jukes, Green, and Harry Perkins (who suffered multiple life-changing wounds and had a leg amputated before returning home). Missing from the County Press report was former fireman and Leading-Stoker Arthur G. Bull, who wrote in appreciation of tobacco sent to him by the brigade from H.M.S. Cochrane. Another displaced Newport fireman was Sergeant Harry Hall, who wrote home from - my little dug-out between the bushes - somewhere on the Gallipoli peninsula.

When news of Second Officer Whittington’s death reached Newport, Percival Edgar Shields was appointed as his permanent replacement. Within weeks, Shields felt compelled to do his bit in the military and departed. Fireman No.1 Frederick Appel was appointed Acting Second Officer, Sidney Percy Scott became Fireman No.1 and Philip Clack, a slater of 61 Jubilee Cottages, New Street, was welcomed as a rarity – a new member aged only 33.

For someone of that age to suddenly join a fire brigade in the middle of the war it may have been that Philip Clack was a conscientious objector. In some brigades the arrival of conchie’s was thoroughly unwelcome, but pragmatism generally prevailed – they needed firemen. The root of the issue lay with central Government. For decades Westminster had resisted all suggestions that firefighting should be set on national guidelines in a similar format to the armed forces. Failure of Government to address the concern in any form led to the creation of 1,600 disparate services across the country without any central guidance. This was coupled to a complete ignorance of the firefighting needs of the country in time of war. Twenty years later in preparation for the Second World War the fire services were afforded protected occupation status in a schedule to the Act of military service – in the First World War no such protection existed. The only countrywide organisation acting on behalf of the need for home fire protection was the National Fire Brigades Union. In Spring 1916, in the wake of the Military Act, the NFBU began canvassing fire brigades to maintain an adequate firefighting force during wartime. When an NFBU letter arrived at the Guildhall, the Mayor was recorded in the County Press to have remarked – We had better let a few houses burn down than stop eligible men from serving. His sentiment invoked no objections.

Newport firemen amid the debris of a fire at The Star Hotel.

A steady source of fit young men was directed to the fire services by the Military Tribunals. These panels, present in each borough and town, generally comprised retired senior military officers, clergymen, esteemed society ladies, seasoned local politicians or lawyers. Generally working in groups of three, the Tribunals sat in self-righteous judgment of applications for deferral of military service. Often these were from men with high dependency families, sole proprietors of small business, those in vital skilled occupations and conscientious objectors. Deferrals, where agreed by the Tribunal, were usually temporary in nature and subject to six-monthly reviews. They were always associated with an implication for the men to undertake some work of national importance in addition to their primary occupation. This often saw them directed into the ranks of the local fire brigade. Newport received its fair share. Some were keen to do so, others were not so enthusiastic. The six-monthly reviews were to prove a thorn in the side of Chief Officer Mursell. Often, on little more than a whim, the Tribunal would decide that the man was to be ordered to undertake military service regardless of his situation – just at the point when a few drills and a bit of experience was beginning to mould him into a useful member of the brigade.

Established Newport firemen who didn’t wish to serve in the military also had to apply to the Tribunals for exemption. 38-year old Newport fireman Harry William Parnell, married with six children, working as undertaker to the prison and military authorities, was granted exemption on 30 May 1916 – on the basis that he remained a fireman.

Emphasising the inconsistent approach - nine days later Parnell’s firefighting colleague Percy Snellgrove, of similar age and position, was denied exemption and ordered for military service. Frederick Wapshott, a carpenter of St James’s Street was directed into Newport Fire Brigade by the Tribunal in the same month that news broke of the death of Frank Rann of Pyle Street, who was briefly a fireman being before called up and killed in action with the 14th Royal Warwickshire’s aged just 19.

Chief Officer Mursell’s desperate bid to maintain an effective firefighting force throughout the First World War was continually hampered by central Government apathy, and the capricious resolutions of the Military Tribunal.

In the post-war Borough, the Brigade reformed with those of its members able and willing to return from military service to that of firefighting. Many did not, some were not physically or mentally capable, and some were left buried in the corner of a foreign field.

Newport Fire Brigade, circa 1919. Four of the men appear to be wearing ribbons, three or possibly four on the bar, suggesting military service during the war.

In the years before the war, the Isle of Wight Fire Brigades Federation had declined into almost total abeyance. By the early 1920’s Chief Officer Mursell recognised that the rebirth of the Federation, along with its values, camaraderie, and competitions, could prove vital to a resurgence of Isle of Wight firefighting. He called and chaired a meeting of the Federation at the Guildhall fire station on 13 March 1920. Alongside Mursell were his counterparts from Cowes, East Cowes, Ryde, Sandown, and Ventnor. The minutes suggest a lukewarm approach to the future of the Federation, but it was a beginning and one that Mursell, as standing chairman, laboured at for several years before succeeding. In 1924 the first IWFBF drill competition since before the war was staged at Sandown, under the chairmanship of Nicholas Mursell.

Despite his success with the Federation, Mursell’s own Fire Brigade remained badly let down by the Corporation’s lack of vision and investment. When the Island’s first motor fire engine, a gutsy Leyland Braidwood purchased by Ventnor, attended its first fire at Trinity Terrace on 10 April 1923, Newport remained dependent on an incomparable manual engine featuring technology unchanged since the 17th century.

The matter was highlighted on 18 October 1924 when it took the Brigade fifty-minutes to obtain the horses and haul the engine to a fire in Gatcombe. In reflecting a fine job done by the firemen, despite the handicapping effect of their equipment, the County Press remarked – is it not time that the County Council and the Newport Corporation combined in installing at the Island metropolis adequate means of combating fire?

Eventually the pressure on the local authority tipped the balance. Sadly, the exact date at which Newport leapt from manual to motor engine has been lost in the documents disposed of in 1974. The earliest definitive reference is from a County Press report of a Brigade Sub-Committee meeting held on 13 July 1927, where the following recommendation was made – That a reduction in the number of the fire brigade should be made, as owing to the provision of a motor fire-engine the sub-committee are of the opinion that a saving might in this way be affected in the annual cost of the upkeep without loss of efficiency. Press reports evidence that the sub-committee proposal was adopted and acted upon, but how many firemen’s positions were cut remains unknown.

The sub-committee also recommended that the rule regarding enforced retirement at the age of 50 was to be enforced. At the time Nicholas Mursell was already in his mid-60’s. Perhaps it was for this reason that the Chief announced his imminent retirement to take effect in New Year 1928 – after 35 years of service. But plenty was to happen before that.

By 1927 brigades in Ryde, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor had been fielding powerful motor fire-engines for a few years, such as the Leyland Braidwood FE, and Dennis Turbine's. Newport’s Corporation observed the options, received recommendations from Chief Officer Mursell, ignored him and went for the cheapest available – a comparatively feeble 30-cwt Ford Stanley fire engine.

Newport's low-powered Ford Stanley fire engine.

In the very least it finally brought Newport up to date. However, it came at the frustration of Chief Officer Mursell and to the humiliation of his men when gathering with their mickey-taking counterparts from other brigades at Federation events – something of a throwback to the days of the Black Rooks. Newport’s councillors always left their brigade one or two steps behind the rest. However, the Ford Stanley earned its place on the night of 4/5 October 1927 at a major incident where Chief Officer Mursell excelled in unprecedented circumstances and left a legacy for IW firefighting.

What began as a small fire in the workshop to the rear of Wadham’s store in St James’s Square, was enabled by the store being closed and the structure being out of public view, to evolve into a major blaze that threatened the entire block of valuable businesses and property encompassed by St James’s, the High Street, Pyle Street and St Thomas’s Square.

On the previous occasion when the town experienced a major blaze, at the Jordan and Stanley’s store in 1908 (referred to above), assistance was forthcoming from Shanklin with what at the time was the latest technology in steam fire engines. However, these devices still required horsepower to be brought to the scene of a fire. Shanklin’s turnout time of 35-minutes was considered excellent – but on the night of 4/5 October 1927, when Chief Officer Mursell realised the scope of the potential before him, his calls of assistance heralded a response by a mass of motor fire-engines in a fraction of the time.

The fire was first identified at 20:45 by members of the Victoria Sports Club who were meeting at Unity Hall. To the rear of the hall was a small yard, from across this open space the orange glow and crackling of burning timber alerted the sportsmen to the developing catastrophe.

Fortunately, the Borough firemen, who had just participated in a civic procession and service at St Thomas’s, were still uniformed and in the vicinity. Their short dash to obtain the engine and return to the spot allowed for a rapid turnout. Chief Officer Mursell took the view as reported by the sports club and immediately realised both the scope of the potential loss to the town, and the difficulty in accessing the fire to fight it. With the Ford Stanley pump running to its absolute maximum output, he was able to position firemen with jets of water directed down from the roofs adjacent to St Thomas’s Square, and a further two hoses that worked through Unity Hall, and the adjacent Wheatsheaf Hotel and yard beyond. Here the firemen at the front met an overwhelming thermal barrier.

With combustibles surrounding the source of the fire already yielding volumes of smoke through heat decomposition, Mursell knew that he didn’t have long to prevent the entire block from becoming involved – with little delay he tasked the Police with sending messages of assistance to Ryde, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor. Of that moment, the County Press wrote - For a time it seemed hopeless to expect them to prevent the flames spreading to several adjoining premises.

Mursell had been the officer in charge 19-years earlier when he called Shanklin to Nodehill and waited for 35-minutes. This delay, whilst unhelpful in terms of containing the fire, allowed plenty of time for him to organise the fireground and have a clear plan for Captain Oscar Rayner’s men when they finally arrived. In 1927 Mursell, probing into the areas where he’d sent his men to check on progress, had remarkably little time to consider a plan before he was besieged by the powerful engines, crews, and Chief Officers of all four brigades to which he’d despatched the plea for help.

The Wadham’s incident was notably the first of what today is a common course of events. Yet here for the first time on the Island, multiple motorised fire engines responded from different destinations many miles apart and converged to weld as one fighting force in the battle against a rapidly developing enemy. The report written by the County Press correspondent unwittingly highlights many outstanding features of fire command and in the aftermath, much was made of lessons learned in the art of mutual assistance of motor pumps. For the first time in the Island’s firefighting history, it became apparent that assistance wasn’t just available - it was available rapidly! Had this incident occurred just a few years before, the response times from the East Wight coast brigades would have involved obtaining horses, harnessing them to the machine followed by hauling the steam pump for forty minutes to an hour in the direction of Newport. Timings in the Wadham’s report indicate that Mursell was swamped with multiple additional men and machines as soon as twelve minutes.

No manual had been produced to dictate the formalities of rapid multiple brigade attendances, there was no precedent set for such a fast moving and changing environment to which Chief Officer Mursell could refer. He simply had to make it up as he went along and at a pace that matched the rapid arrival of the assisting forces at his disposal and the developing scale of the blaze. Without any of the paraphernalia used to identify command individuals seen on today’s fireground, and without radio communication, the men of Newport, Ryde, Ventnor, Sandown and Shanklin didn’t need to trust to anything other than instinct, common sense, and the man in charge. It was Mursell’s patch and therefore it was his command. He told them what his men were doing and what he wanted them to do, and they did it. The fact that his decisions were correct, and the men well led, are down to the commander’s character, the supportive compliance of his counterparts, and intuition. This was a fire, and a threat, beyond anything Mursell had experienced, or had the opportunity to prepare for - no exercises were held, or theoretical treatises existed from which he could do so.

In the context of the Island’s firefighting evolution, the story of the Wadham’s fire was an epic, and Nicholas Henry Thomas Mursell was its author.

Three months later, as announced, he retired from the brigade after 35 years’ service, 33 as brigade commander. Nicholas continued as landlord of The Castle Inn until ill-health forced him to retire in 1942. Chief Officer Mursell’s service, spanning the entirety of the volunteer years and his key role moulding the professional crews, encompassed a remarkable era in Newport’s firefighting history.

In the second week of January 1928, Mursell handed the reigns to his long standing understudy Percival Edgar Saunders Shields. The 42-year-old of 17 Quay Street worked full-time as financial clerk to the Corporation and had served with the brigade since before the war, prior to which he had been one of the brigade’s callboys. His only break in service being the time he spent as Adjutant (Captain) of the 4th Hampshire’s in France during the conflict. Given his weight of responsibility to the Borough through his primary occupation, concerns were raised by Mayor and Councillors, that they were placing too much upon his shoulders. Percival agreed to a one-year trial with Sydney Percy Scott as his deputy.

Clearly the task was to the liking of Chief Officer Shields and the satisfaction of the Corporation. His tenure extended well beyond the trial period, during which he led Newport’s firemen to their most successful period in drill competition and through some challenging incidents. In 1932 he evolved the role by adopting the task of fire prevention. In a first for Newport, Percival carried out inspections of all premises licensed for stage plays and cinematographic exhibitions. At the Chief’s suggestion, the Medina Hall cinema installed a Pyrene Co., pressurised Carbon Dioxide flooding system. Designed to deploy the oxygen displacing gas automatically in the event of fire occurring in the celluloid reel, it was also capable of shutting down the projector power supply.

His position as Corporation accountant placed him in a privileged position. Having intimate knowledge of the public purse, Percival knew better than anyone whether it was the right time to canvass council to fund new equipment. The Brigade benefitted substantially from the additions of the Antifyre Pistole, the revolutionary placement of hydrant markers across the Borough (years before it became statutory), and chemical extinguishers strapped to the side of the Ford Stanley, plus over 1000’ of new Mondix fire hose.

1928 August 6 - the wedding of Fireman Edwin Hurry, whose first wife passed away in 1924.

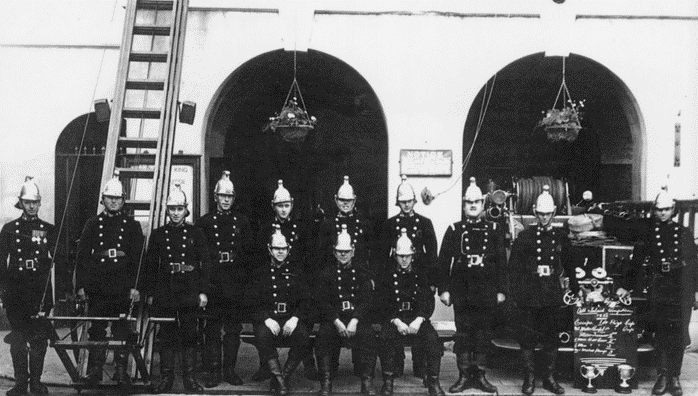

Newport Fire Brigade. I have seen this photograph in various publications and websites dated 1932, but carrying a caption remarking on the absence of Chief Officer S.P. Scott - however Scott wasn't the CO until July 1934 so my estimation would be then or thereabouts. The men who do appear are known as follows - B. Kelleway, Percy Guy, Edwin Hurry (sometimes recorded as 'Urry'), Hector Percy Scott, L. Holbrook, R. Rutter, R. Ball, Second Officer William Phillips, J. Taylor, S.Scott. The seated three at the front - H. Green, Arthur Pointer, H. Stevens.

Antifyre Pistole, and charges.

Utilising his financial acumen, the Chief encouraged his men to contribute to a Christmas club over the course of each year. In the week before the 25th, he would organise a party for the men and their families where they would receive their club payouts, including the modest but valuable interest accrued. Shields’ influence in the council chamber and compassion for all living things enabled the brigade to respond to reports of animals in peril. At the end of 1932 the RSPCA wrote to Chief Officer Shields in thanks for the brigade’s rescue of three cats, a hen, and a pigeon over the previous twelve months.

However, the expanding needs of the Borough, and the subsequent effect on Percival Shields day job, compelled a revision in the summer of 1934. Alderman Blake, speaking on behalf of the Council, stated that he – regretted that he had been obliged to give up the post. Of interest is the reflection of the man himself on the announcement of his resignation – I have been interested in the work since boyhood, having started as a callboy and having filled nearly every office in the brigade. I have had experience of firefighting in England, Scotland, Belgium, and France, before I took over charge of the Newport Fire Brigade and some of the biggest fires I’ve tackled have been here. Owing to the increased amount of work I regret that I am unable to continue these duties.

Percival Shields’ six-years as brigade commander had been comparably brief, but not without remarkable progress and achievement. Without further ado, Council accepted Percival’s recommendation that his deputy, Sydney Percy Scott, be appointed as Chief Officer. William Phillips, one of the original volunteers and a First World War veteran, was selected by Scott as deputy (Second Officer).

It is recorded that within two-months of Sidney Percy Scott’s tenure, the brigade acquired its second motor fire-engine, but the groundwork had been done by Percival Shields in his final months as Chief Officer. Unsurprisingly the outgoing Chief had ensured that the mistakes made by cheaply purchasing the Ford Stanley was not repeated. In the first week of March 1935 the brigade took possession of a 55hp Dennis engine (pictured below, a poor quality extract from the IW County Press) capable of delivering 450 gallons of water per minute from two outlets, in addition to a first-aid hose reel – an altogether preferential and more capable machine in comparison to the Ford Stanley.

A matter that sets Chief Officer Scott aside from his predecessors, notwithstanding his immense height, was his exposure to the opening chapter of Air Raid Precautions. Incredibly, he was not invited to attend when the Guildhall hosted Major Stuart Blackmore, O.B.E., Chief Medical Officer to the Home Office, who addressed the assembly on the threat of invasion, aerial bombardment, and gas attacks on the civil population, in December 1936.

Scott’s attention was meanwhile distracted by minor squabbles among his men, most notably the qualified drivers, of which the brigade possessed only three. The discontented trio undersigned a letter to the Chief Officer complaining about rules imposed on them concerning their total availability on Sunday’s. Subsequently a hastily formed sub-committee investigated their complaint and conducted interviews with all three. The committee’s findings resulted in the immediate dismissal of C.H. Heal and Frank E. Way, and the recruitment of qualified drivers Leonard G. Holbrook, a motor mechanic of Wilver Road and lorry driver H. Stevens of Trafalgar Road. In the aftermath the pair published a letter in the County Press complaining of their exploitation and comparing it to non-driving members of the Brigade who, on Sundays, could go where they chose.

Having been supported by Council concerning the Sunday arrangement for drivers, Scott was in the firing line in July 1938 regarding his autocratic appointment of firemen of his choosing. Reporting to Council the General Purposes Committee insisted that applications should be advertised and come before the appropriate sub-committee. Mr Whitehead asserted that I do not agree with the Chief Officer choosing his men. The meeting then proceeded to a broader analysis of the Brigade, a dissection of what they considered an inadequate organisation for drills, and that – the brigade should be reconstructed throughout! Scott was also under pressure for the rapid rise of his son, Hector Percy, who although a young man was promptly appointed First Engineer and steadily gained an increasing influence over brigade operations. Whilst the matter undoubtedly hints of nepotism, as history was to prove, the recognition of Hector Percy Scott as a man of redoubtable character and leadership principles was to propel him into the most difficult assignment encountered by any Isle of Wight fire officer in the history of the county’s fire services, including up to the present time – and one from which he emerged with unparalleled credit.

A cartoon from the IWCP following the IWFBF drill competition of 31 July 1937 – a satirical reflection of Chief Officer Scott’s notorious height.

By 1939, the Corporation, like all local authorities, were still getting to grips with the requirements of the Fire Brigades Act 1938, and the Air Raid Precautions Act 1937 – which later in 1939 was superseded by the Civil Defence Act. For that purpose, a Fire Brigade and ARP Sub-committee was formed.

In January 1939 the sub-committee made two significant recommendations – the appointment of a full-time Chief Fire Officer, and the establishment of a new purpose-built fire station. Immediately the proposals were presented in Council the chamber erupted with those who, in words spoken by Alderman Whitcher, clearly had no concept of events in the Spanish Civil War or appreciation of central Government fear for the United Kingdom in the imminent aerial battle against Nazism – We only have a few fires, mostly small ones!

Fortunately, the majority did see the need, in particular the legislative requirement to furnish the Home Office with a clear and considered plan for the future establishment scheme for both the regular fire brigade, and the ‘emergency fire brigade’. i.e., the Auxiliary Fire Service. The Town Clerk and Surveyor were tasked with considering sites for the development of a fire station, while an Establishment Committee was formed to consider the appointment of a full-time Chief Officer, among other tasks.

By March the initial batch of Newport AFS were under instruction led by Chief Officer Scott. Several of his men had also become involved in the study of airborne incendiary bombs and had shared their knowledge at formal sessions with members of the ARP. As Spring 1939 progressed, the rate of increase in regular brigade, AFS and ARP preparations for war took up more and more of Chief Officer Scott’s time and energy, an extreme extension of his original terms of office, for which, like his contemporaries across the Island, he received no additional support or pay.

The solution, as agreed with the General Purposes Committee in January, was concluded in April when it was announced that 33-year-old Dartford AFS instructor Stanley Fairbrass was to be appointed the Borough’s new Chief Officer. Where this left Sydney Percy Scott is initially unclear. On 22 April he attended an IWFBF committee meeting as Chief Officer of Newport, but four days later Mr Fairbrass arrived to take over the position, at which stage the Corporation publicly thanked Scott for his 30 years of service. Stanley Fairbrass and Ryde’s Max Heller became the first two full-time paid firemen in IW firefighting history. Although Heller had been at Ryde since 1937 it is difficult to verify which was the first to obtain full-time status.

Stanley Fairbrass, top - as a young fireman in Chiswick, bottom - when a Divisional Officer of the National Fire Service.

Within three weeks of the declaration of war, the Island’s combined district authorities agreed unanimously on a plan that promoted the principle of co-dependency over two years prior to the formation of the nationalised fire service. Stanley Fairbrass was to remain Chief Officer of Newport Fire Brigade but was to serve concurrently as commander of all IW fire brigades and AFS contingents. In effect this elevated Fairbrass to a level of principal officer, but no additional rank title was afforded – only the authority that was bestowed on him to fulfil the tasks. In effect, from his cramped office, Fairbrass was to develop a system for plotting the disposition and redistribution of firefighting resources as and when required to any part of the Island. His rank remained Chief Officer, but he accepted the role on the understanding that his contemporaries in West Wight, Cowes, East Cowes, Ryde, Bembridge, Sandown, Shanklin, and Ventnor, would yield to his instructions without hesitation. This elevated position effectively separated him from the usual duties of a brigade Chief Officer. At Fairbrass’s recommendation Arthur Pointer was appointed Station Officer of Newport, a position that warranted the responsibility and authority of Chief Officer, if not the title. Shortly after Pointer left for SARO to act as Station Officer of the works brigade. Again it was Fairbrass's recommendation that resulted in Senior Fireman Hector Percy Scott's appointment to Station Officer. In effect this meant, for good reason, if Fairbrass wished to turn out his own brigade he first had to pass the order to the Station Officer. This ensured consistency in the process of turnout for all brigades and AFS. Additionally, to lighten the load on regular firemen and officers, Newport’s growing number of AFS volunteers were to be trained by Hector’s father, retired former Chief Officer Sydney Percy Scott.

At some stage shortly before war the Fire Brigade was ordered to vacate the ground floor of the Guildhall. A Government document, written in 1940 at the time of application to build the South Street station, states that the Newport Borough Council deputation reported that for a brief period the fire brigade was accommodated in a small shed, without detailing the location. The desperate requirement for an improved situation coincided with a need to identify temporary accommodation for AFS appliances and equipment. Bringing the two disparate firefighting factions together consolidated the matter and the combined forces were accommodated at the South Street Corn Exchange, with the vehicles positioned outside. But this was to prove a nuisance as the twice-weekly corn market required their removal.

In the meantime, the Clerk and Surveyor had identified a derelict slum of four cottages off South Street known as Abraham’s Court as a suitable site for a new fire station, comprising an area of 1,925 square yards. In the wake of the news being made public, Mr A. Balchin of College Road (who I suspect may have been the same Arthur Balchin, an NFS fireman), submitted a letter to the County Press, expressing an interesting view that the selected site was – on the outskirts of the town – and this would cause delayed response times. How Newport has changed since then for South Street to be considered the outskirts! Ministry of Housing and Local Government file HLG/51/676 provides details of the plan. In the initial submission, sent by Town Clerk Robert Preston to the Ministry in July 1940, his letter contradicts Mr Balchin’s opinion stating that the site is an extremely central one. Purchase of the land, including costs, was £1050.00.

On a personal note, in the course of researching my family history I discovered that my great grandfather Henry Hall, who may have been a Newport fireman as one by the same name served in the brigade during the appropriate era, was residing at No.4 Abraham's Court when the 1901 Census was recorded.

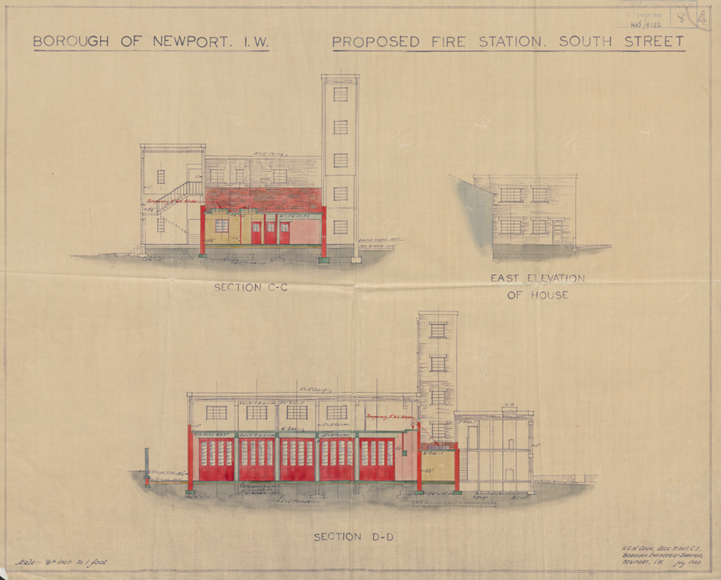

On 23 August 1940, Robert Preston and Chief Officer Fairbrass were interviewed by the Home Office Fire Brigades Division. At the meeting the two representatives were able to furnish the Home Office with technical drawings of the proposal. Further drawings were added in the following months, as dated on the originals shown below.

Areas of the technical drawings highlighted in red are those permitted for build during wartime. The remainder was to remain in abeyance until after the war.

Preston and Fairbrass emphasised to the Home Office delegates that their proposal was for a peace-time fire station. The ministry was appreciative of the distinction but favoured that due to the war situation and pressure on supplies of building materials, the plans should be reduced to the portion comprising the five appliance bays, battery room, boiler house, office and watchroom only (the parts highlighted in red in the plan drawings). The Ministry looked favourably on the dimensions of the proposed bays, noting that the depth would permit a Home Office supplied trailer pump in each bay in addition to a motor fire engine.

The Home Office agreed the plan in principle, the only caveat being liaison with their own technical advisers concerning economies of materials used. Those considerations were mailed to the Town Clerk on 2 September 1940 and were factored into the reduced building plan. In the main this comprised substituting the steel frame for one of steel-reinforced concrete, in addition to abandoning the plan to plaster and paint the walls of the appliance bays.

The Borough estimated the building cost, not including purchase of the freehold land, to be £3,335 based on the lowest tender submitted by building contractor Mr G.E. Banks of Sandown. For the clarity of the builder, Home Office and Borough, Borough Surveyor Mr Cook submitted the finalised plans and a written specification at a later date (original copy undated).

The wheels of bureaucracy turn slowly. It was almost two years and after the advent of the National Fire Service that Newport’s Central Fire Station, finally opened on 18 February 1942. Prior to that the regular brigade and AFS managed their wartime affairs awkwardly from the Corn Exchange.

Meanwhile having relocated his county fire HQ and resources to a small office at the Corn Exchange, Stanley Fairbrass may have been relieved that the Phoney War gave him breathing space to test and improve his strategy before it was depended on. His Isle of Wight arrangement became a small cog in a nationwide reinforcement scheme imposed by the Home Office – although it was over and above the ministry’s requirement.

A major fire, of accidental cause and no connection to the war, at Morey’s on 17 January 1940 afforded the perfect opportunity to test his scheme in real time, thankfully without the additional stress of further attack from the air. In the aftermath a letter received in Council from Whitehall, confirmed that not only did Fairbrass and his operators process the multi-brigade turnout faultlessly, but it was also the first live call-out in the country to be communicated through the new national Control Room at Horseferry House, London.

Although the blaze was enormously destructive to the building, stock, and stores, it was contained to the site of origin and large enough to provide a perfect opportunity for the combined regular brigades and AFS to put into practice the skills of integration and command that were to prove so important over the coming years.

One of the many Beresford Stork trailer-pumps, seen here in the possession of Firemen Wickett and Bourne of Binstead AFS.

This included the first occasion on the Island at which Home Office supplied Beresford Stork trailer-pumps were brought into action. The skills required in operating these devices were a vital factor in wartime water supply, water relay, and firefighting. By New Year 1940, trailer-pumps were being transported by requisitioned or generously loaned personal vehicles. In February, responding to notification from the Home Office that this potentially unreliable scheme should be reduced wherever possible, Newport’s councillors agreed to purchase a range of second-hand cars to be adapted and dedicated for the purpose. The part of the marketplace allocated for use by the brigade and AFS became increasingly cluttered with wheeled machines.

Ten days later the County Press reported details of another first for Newport firemen. A Red Cross supplied Ambulance that had been positioned at the marketplace temporary fire station in early November, had already been deployed by the brigade, with a crew of two firemen, to 41 callouts.

By then even those in council who had cringed at the expense of the proposed South Street fire station, discussed the desperate need to expedite the plan. Over the course of winter 1939-40, seven pumps froze solid due to being exposed to the elements at the market – one of which cracked a cylinder head and block. Given Newport councillors legacy of dismissive irritation with fire brigade matters prior to 1938, a statement issued by them in July 1940 evidenced a complete revision – the Fire Service has priority over practically everything else. With Chief Officer Fairbrass effectively commanding the Island’s fire services from his modest accommodation at the Corn Exchange, and the marketplace rapidly filling with the majority of the Island’s allocation of men and machines, the effect of the war was to gradually remove firefighting primacy from the formerly dominant East Wight brigades to the centre of the county.

Chief Officer Fairbrass (front and centre) and the regular brigade firemen of Newport, photographed at the marketplace, winter 1939.

The advent of the National Fire Service, launched on 18 August 1941, sealed the orientation of Isle of Wight firefighting for the remainder of the war by reinforcing Newport as the hub at the centre of the wheel of Isle of Wight fire services, featuring several spokes comprised of established fire stations (some with sub-divisional control rooms) and the myriad of auxiliary stations, sub-stations, fire posts and training centres across the Island all under the banner of NFS Fire Force 14 Division D of Region 6 – Southern.

By then Stanley Fairbrass’s incredible achievements with the pre-NFS IW scheme had been noticed at the senior level. Within weeks of the NFS launch he was favoured and appointed as Divisional Officer in command of Bournemouth. Newport’s firemen and councillors felt his loss deeply. His replacement, Thomas J. Upward, had been commander of the Cowes Combined Fire Services (Cowes, East Cowes and AFS) since 1939. In this role he appeared successful and the NFS had little doubt in appointing him as the Island’s Column Officer in charge of 14D. Sadly being elevated in rank and responsibility seemed to unravel the good upon which he’d built his reputation. By mid-December 1941, just two months into his appointment, he had caused such a ruckus among the Island’s firefighting fraternity, in addition to upsetting the sensitivities of several councillors, that the NFS removed him from the Island, posted him to an office based administrative role in Portsmouth and demoted his rank to Station Officer.

The vacuum created in the Island’s NFS required speedy, but purposeful plugging. Wisely, Fire Force headquarters sought an Island man with locally recognised integrity, proven ability and, distinctive of NFS leaning was of a generation younger than that typical of pre-war established Chief Officers (most of who were in their 60’s). Under NFS protocols Hector Percy Scott, who had been Station Officer at Newport under Fairbrass, was made Company Officer of Newport and district, and in that role had already impressed NFS Fire Force command. Aged just 30, he was made Acting Column Officer – effectively in command of every fireman, firewomen, and appliance across the Island. Whether the Acting element suggested he was on trial pending a substantive appointment, or that the intention was to replace him with an alternative man when one became available, we will never know, but fate was to intervene and force a decision in the months that followed.

Six-months later, and not a moment too soon, the South Street fire station, designed and built under the direction of the Borough Council, was handed over by the Mayor Captain J.S. Brown, to the National Fire Service on 18 February 1942 amid a grand ceremony.

A parade of 150 firemen and firewomen assembled at Victoria Recreation Ground and were joined by the band of the Bournemouth NFS, arranged by Stanley Fairbrass who made a brief return to the Island to see the culmination of the fire station project he had begun in 1939.

With Column Officer Scott at the head, the band and ranks of the NFS marched in procession from the Recreation Ground, via the High Street and Pyle Street to Church Litten, repeatedly playing the jolly tune of the recently written NFS March, where all were called for ‘eyes right’ as the Mayor took the salute from the dais as the column continued down South Street to the new station where they paraded before Fire Force Commander A.E. Johnson, M.B.E., Deputy Fire Force Commander J.L. Johnson, Divisional Officer T. Hatchett (all of Fire Force 14) and special guest Divisional Officer Stanley Fairbrass (of Fire Force 16).

With all smartly at the ‘shun in South Street facing the station frontage, the Mayor ceremonially operated the electrical machinery that threw open all five of the bi-fold bay doors. In poured a steady stream of dignitaries, councillors and visitors who were advised that the engine house was capable of accommodating five main appliances and six trailer-pumps. The adjacent control room and facilities, representing the most modern and efficient centre of firefighting on the Island, were admired by all.

Initially, following the pattern set by Regional NFS Headquarters at Marlborough House, Reading, Newport was designated as NFS station 14D4W. Shortly afterwards it became apparent that it was more sensible for IW fire stations to follow the pattern of District numbering applied by the ARP, within which the Newport district was number 1 – and it is from here that the station’s irreplaceable designator has its origin. In full the South Street station was known as 14D1Z – defined as – Fire Force 14, Division D, Station 1, featuring a sub-divisional control room (defined by the presence of ‘z’).

No photographs of the opening of the South Street station have been discovered. However another ceremonial event a few months later was captured as shown above, which currently represents the earliest known image of the station after its opening.

But this was not where Acting Column Officer Scott was to be based. Station 1 was a fire station, not a headquarters. For this purpose, The Grange, a country house on Staplers Road, considered far enough outside of the town to be at little risk of aerial attack, was requisitioned and repurposed. With a large ground floor room fitted out as Mobilising Control, a stout above-ground air raid shelter built in the grounds, and HQ garaging and vehicle workshops established to the rear, Scott and his staff moved into a palatial existence compared to the borrowed office space at the Corn Exchange.

It was the investment in these facilities, the well-appointed five-bay station, and the detachment of headquarters staff to alternative accommodation fit for purpose, that enabled the Island’s fire commanders, led by Acting Column Officer Scott to guide a cast of nearly 1,000 fire service personnel and approximately 50 fire engines, including self-propelled pumps and trailer-pumps, when the Island faced its most severe test on the night of 4/5 May 1942.

The ghost of Sunningdale Road Fire Station, a drop-kerb that extends across the frontage of two post-war bungalows (screenshot from Google Earth).

But history was to prove that Newport’s firefighting capacity was to almost double before the end of the war, albeit briefly.

On Sunday 23 January 1944, a second five-bay fire station was less ceremonially opened by Deputy Regional Commissioner H. Asbury attended by the Mayor, in Sunningdale Road. So far research has not revealed definitive evidence of the reason for a second five-bay station in Newport.

However, it was most probably an integral and necessary component of a brief period of NFS reorganisation known as the Colour Scheme, based partly on a reduction of the threat from Luftwaffe heavy bombing, in addition to the need for greater fire protection in areas of the south that would soon be swamped with men and materiel for the invasion of Normandy.

An extract of a wide-area aerial photograph (1948) - the only known image of the Sunningdale Road Fire Station.

England and Wales was divided into three NFS designations based on colour. Fire Force’s within the Green zones were to be reinforced but only to bring them up to their nominal strength. Fire Force’s in the Brown zones were to relinquish approximately 50% of their staff and release them to predesignated areas in the Blue zones. Unsurprisingly the Blue zones, which stretched from Cornwall in the west, across the South Coast as far north as Gloucestershire and Oxfordshire, to Kent and continued north along the East Coast to Norfolk, were the staging areas for what would ultimately become known as Operation Overlord – or D Day. These zones were to be substantially augmented by incoming fire personnel from the Central and West Midlands, West Riding, the Northwest, and Wales. It is known that during this period the Isle of Wight welcomed many firemen and firewomen from the Yorkshire area, specifically many from Bradford. Such a large number would require accommodation for their appliances and equipment, in that context the sudden and hurried building of a second five-bay station, for which most of the work was done by Newport firemen themselves, seems less surprising. The designator for this station is unproven. Following NFS doctrine it would most likely have been 14D1Y, but I emphasise that this is an estimation.

In the wake of the successful invasion, it was time for the Colour Scheme personnel to return home. On 23 October 1944 a large celebratory and farewell function was held, beginning with a formal dinner and toasts in the bays at 14D1Z (South Street), continuing with a drink or two and a singsong at an off-station venue, as a mark of appreciation for the massed firefighting personnel from the north prior to their departure.

Sunningdale Road Fire Station was vacated by the fire service less than a year after it opened. No photographs have been located and all that remains of it today is a broad expanse of drop-kerb at the frontage of two bungalows built on the plot in the post-war era.

As the necessity for wartime levels of civil defence on the home front reduced with every passing day of the Allied advance across mainland Europe, the NFS were under pressure from the War Office to slash their manpower and release more men for redirecting into the fighting forces, both in Europe and the Far East. The NFS launched a range of policies to expedite men from the service. By late 1944/early 1945, 14D had been slashed with all but one of the sub-stations being closed. Eleven stations were preserved at Newport, Cowes, East Cowes, Ryde, Bembridge, Sandown, Shanklin, Ventnor, Niton, Freshwater and Yarmouth.

Re-designation of station callsigns was required. With Newport firmly established as the Island’s firefighting centrepiece, it was to retain its number ‘1’ status. In full its late war designator became 14D1. By then the District numbering system applied by the ARP and Civil Defence scheme was rapidly becoming obsolete because the service was reduced at a far greater rate than the fire service, it being assumed that in the post-war world there would be no place for the scheme. Civil Defence was formally stood down in its entirety six days before VE Day. With no reason to follow the ARP District system, the NFS applied a simple numerical system clockwise around the Island, beginning with Cowes as 14D2 around to Yarmouth as 14D10 (an exception was the sole remaining sub-station at Niton, which became 14D8A, as an adjunct of Ventnor station, 14D8).

With the final act of warfare culminating in the surrender of Japan in August 1945, the NFS as a wartime institution was concerned only with domestic firefighting. Although substantial reductions in manpower had partially prepared for that day, there remained a plethora of appliances, equipment, materials, and non-operational buildings over and above the capacity required for the management of what was effectively a provincial fire service.

In 1941 when the NFS was launched, Home Secretary Herbert Morrison pledged that at the cessation of hostilities the control of fire brigades would be returned to local authority control. Those who had enjoyed their years in the borough and town brigades took this too literally, expecting a return to the way things were. When the Fire Services Act 1947 was launched, it was with great anger and cries of ‘but Morrison said!’ that some of the pre-war veterans realised this was not to happen. Herbert Morrison didn’t tell an outright lie, but he allowed the misunderstanding to smooth the way for the NFS.

It was clear to anyone with a rudimentary appreciation of the advantages of reinforcement and redistribution, that the lessons learned during the NFS years, coupled to the innovative experiment overseen by Stanley Fairbrass in the 1939-1941 period, ruled out any desire to return to a status of disparity between town brigades. Perhaps the only surprise is that the National Fire Service was disbanded at all and split into a network of county and metropolitan brigades.

Under the terms of the Act, lsle of Wight County Council were obliged to consider and submit a plan under the Establishment Scheme. With Home Office approval granted, the scheme was to take effect with the launch of the Isle of Wight County Fire Brigade on 1 April 1948.

Events leading to that date were anything but smoothly conducted. In a peculiar local quirk, the Isle of Wight was the only county in the country whose brigade didn’t actually launch until 2 April, but that’s a story for a separate feature.

In 1949 the rear of the South Street site, the so far unused area of the demolished Abraham's Court, was finally repurposed with the construction of an ambulance garage. In 1952 substantial improvements were made to the watchroom.

Following the doctrine of the NFS, in the post-war brigade Newport, which for decades had fielded one of the most poorly funded brigades on the island, was very much the hub of the service. Although some wholetime posts continued elsewhere for a brief spell after NFS disbandment, the long term plan was to staff only Newport with career firemen. By the early 1950's this was the case.

It would be unfair to suggest that the county brigade didn't invest in out-stations, the erection of new stations at Yarmouth, East Cowes and Shanklin evidence otherwise, but major investment was required to bring Station 1 to its full potential. Funding was secured in the mid-1950's and building began on what amounted to the inclusion of the parts of the original 1939 drawings that were denied by the Home Office due to the restriction of building materials. Finally on 30 January 1960, Mark Woodnutt M.P. formally opened the new additions including a first floor above the engine bays, administration offices and facilities and two pole-drops, one at either end of the building (only one of which remains in use today), and an extension on the west elevation allowing spacious accommodation for the duty watch. Further expansions, which deviated from Cook’s drawings, included workshops, garaging, a drill tower and a purpose-built dedicated space for the County Brigade Fire Control Centre, the needs of which had materially outgrown the modest room provided for wartime sub-divisional operations. It appears that Cook’s 1939 plan, showing housing for the Chief Officer and his family, attached to the east elevation, including a garden, never materialised and in the post-war era gave way to the ground floor stores, above, below, and around which was constructed the smokehouse and tunnels training facility that remain in use today. Additional access to the site off Pyle Street was also established at this time.

Sunningdale Road Fire Station, empty since late 1944, was briefly reoccupied by the service in 1948. A statement in the finalised Establishment Scheme submitted to and agreed by the Home Office included use of Sunningdale as a temporary ambulance station under the control of the fire service. The temporary nature of Sunningdale’s use was emphasised in the associated formal submission which closed with – An ambulance station should be built in Newport at the same time and in conjunction with a new hospital or health centre, whichever comes first.

South Street’s Newport Fire Station was under no such threat of vacation and replacement.

Station 1, is the only station to maintain continuous wholetime cover from April 1948 to the present day. The nature of that cover, the personnel per watch, the appliances and equipment, and notably the expanding role of the service has changed incomparably during that time. The primary structure of the 1942 and 1960 constructions has not changed a great deal at all, although secondary internal configuration has been subject to several alterations in recent years.

Newport Fire Station from the air, 1975.

When the Isle of Wight Fire and Rescue Service was combined with its neighbour to form Hampshire and Isle of Wight FRS in April 2021, Newport's role as the hub of a service was reduced dramatically, although it still retains its number '1' designator, fully re-designated as H71.Nevertheless considerable investment has been directed from the new HQ at Eastleigh to generally improve the standard of accommodation at South Street, including the costly and protracted need to remove the asbestos components installed in 1960.

Today, June 2024, the site accommodates two first line pumping appliances, in addition to several special appliances. Wholetime firefighter accommodation and day rooms remain in the west wing of the station, as designed in 1960, but with some radical alterations in recent months including relocation of the kitchen facility. The Isle of Wight hub of the Fire Protection department is located in office space on the first floor above the appliance bays, sharing space with staff of the Community Safety department. Other buildings include the smokehouse, still in regular training use, and the workshop that now serves island based appliances under the direction of its parent department at Eastleigh. A gymnasium and store rooms are present in the ground floor of the structure to the rear above which resides the island's Group Commander, the two On-call Support Officers that each look after out-stations to the East and West respectively, and the former Fire Control Room, now virtually unrecognisable as a state-of-the-art meeting room.

In the combined service Newport's status has been somewhat downgraded in the bigger picture, but it still represents the largest island station in terms of vehicles, number of personnel and 24-hour immediate availability.

If you have enjoyed this page, please consider making a small donation to the Firefighters Charity.