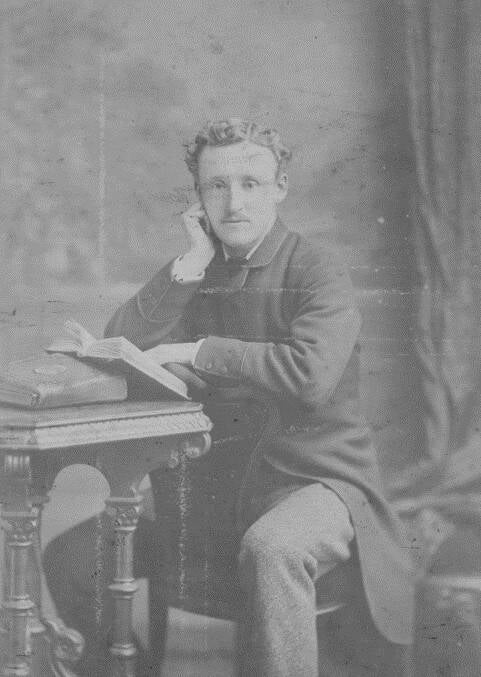

Captain Charles Langdon, born 11 May 1859, was to become captain of Ryde Fire Brigade, founder of the Isle of Wight Fire Brigades Federation, its first Honorary Secretary in 1894 and was serving as its final President when he passed away on 25 January 1944, the year before the Federation finally folded following the end of the Second World War.

Charles was the son of John and Mary. His father was a well-known building contractor who served as superintendent of Ryde Fire Brigade from 1864 until poor health compelled his withdrawal from the service five years later.

Charles was the fifth of eleven children and naturally evolved to become an asset in the family business which provided employment for 58 persons at the time of the 1871 Census. His father’s premature death aged 51 in 1879, when Charles was approaching 20-years-old, compelled the young man to step up and take greater responsibility for the day to day running of the business.

Five years later, 26 June 1884, he married Annie Jane Newman. They were to have four children, Ethel (1886), Florence (1887), Arthur (1889), and Percy (1890).

By the time of their two son’s births, Charles had been voted into the role of Captain of Ryde Fire Brigade, by seven votes to two ahead of Mr H. Jenkins - to fill the boots of the inimitable Captain Henry Buckett. Charles’s appointment was confirmed by the Public Works Committee on 26 January 1889. Other than childhood memories of his fathers’ service with the brigade, Charles had no direct experience of fighting fires. But for a young man he had plenty of experience of organising and directing working men in outdoor, potentially hazardous environments, in addition to being a skilled administrator.

Charles’s first task was to undertake a detailed inventory of the brigade’s equipment and appliances.

After submitting what was needed to bring the brigade back to full efficiency, the Public Works Committee, who under Alderman Dashwood had seized ultimate power away from Captain Buckett in 1886, came under pressure for their lack of attention. A temporary sub-committee was formed to investigate Charles Langdon’s findings.

The sub-committee forged ahead and obtained quotes for resources and work necessary to appease Captain Langdon’s demands. They delivered their findings to the Council. £39 2s 6d was needed to purchase certain unspecified materials from Shand Mason and Co., and a further £13 7s 6d, was required to employ Mr Love to repaint the engine, hose reel cart, and escape ladder, and to repair the engine’s braking mechanism.

Under pressure from Council concerning the extent of the findings and associated costs, Alderman Dashwood disingenuously argued that the brake was never used except outside the borough, and aimed a pointed remark at the new captain, stating – We never had any complaint before we had this ‘new broom’, who seems inclined to sweep pretty clean, at all events at the beginning. Dashwood continued by suggesting that Mr Love’s quote for the painting was throwing money on sentiment.

Charles's axe, belt with axe pouch, and safety line, generously bestowed to my trust by David Langdon, his great grandson, for use at IWFBF displays and presentations.

Alderman Barton not unreasonably remarked that without a brake the engine would be dangerous, and Mr Riddett asked if there had been any occasion of it running-away with the firemen. The Borough Surveyor recalled a time during the superintendence of Charles Langdon’s father when it occurred in Queens Road, coming to a rapid stop in a hedge and throwing the men off. Dashwood conjectured that the occurrence was due to a liberal supply of refreshments, and that the brake played no part. Clearly the Alderman felt he was under pressure and was scorned that his Public Works Committee, who had insisted on taking control of the brigade, were being placed under the spotlight by the young man they had recently appointed to the post of captain.

Mr Riddett was more objective – the new captain is taking a great pride in the work, and we ought not to spoil the engine for a little paint. Mr Sweetman also supported Captain Langdon’s demands – the appliances for protection against fire should be in a perfect state, and every fireman should have an axe and belt. Four are no use to 15 men, they might be suffocated before they could burst a door open. If men risk their lives, they ought to be provided with the necessary appliances.

Mr Pollard was less enamoured by Langdon’s needs, alluding to them being of a frivolous nature – We should not invest in pride, it is a most unprofitable thing. Mr T.F. Ellery spoke in support of Captain Langdon and fired his guns at the Public Works Committee – In January 1886 the Council ordered the Committee to thoroughly reorganise the brigade, but nothing has been done. If any accident occurred through the absence of axes, the Council would be morally responsible.

The minutes evidence the matter descending into a clash of personalities more than an objective appraisal of what the fire brigade needed. The press report closed with the words of Alderman Colenutt who stated – I shall have no more to do with the captain!

Charles Langdon not unreasonably launched into his new duties with a detailed inspection of the equipment for which he was made accountable. The outcome was, as he was to find repeatedly throughout his tenure, subject to the vagaries of those in power rather than an objective appraisal of the practical needs of an emergency service. This inevitably led to making enemies - he was far from the only Isle of Wight brigade commander to suffer the same experience.

Charles was blessed with many weeks of getting to know and drill his firemen before commanding them at his first fire on 21 April at the Royal Pier Hotel.

The coffee shop fire was so brief and smartly dealt with using a hand extinguisher and water from the hotel’s own roof mounted tank that many of the patrons were unaware it had happened.

Two days later the brigade was called to a more threatening outbreak close to the Royal Pier Hotel at the Union Street hosiery operated by Mr A. Bevis. Passengers alighting the 04:00 mail boat, approached the town from the Pier and observed excessive smoke chuffing from the chimney. A 13-year-old boy named Norris was despatched as knocker-up to rouse the firemen and police.

Given the location of the fire, close to a ready water main and fire plug, and with the water turned on at the cock, the brigade attended with only the hose reel cart, leaving the engine at the station.

The IW Observer reported that the brigade – turned out quicker than they have done for a score of years. The remark is positive for Charles but could be considered insulting his predecessor. The truth is that the once indefatigable Henry Buckett’s health had been ailing for some time before his ultimate, but difficult, decision that he could no longer perform as head of the Brigade. In the months before making that brave and heartbreaking decision, his former fearless grip of his firemen loosened and to the men’s shame they allowed apathy to set in. The Observer’s suggestion that it had been the case for a score of years seems sensationalist and not matched by their own reports of brigade activity during the same period.

Detail of the decorative element of Charles's late-Victorian fireman's axe. Initially I wondered if this was a bespoke item, until discovering a copy of a contemporary Merryweather catalogue evidencing the same design. Nevertheless, this is not a mass produced item and would have been a coveted item.

In Union Street, with the hose tapped direct into the fire plug, and water pouring from the branch forced by a head of water located miles away at Ashey reservoir, Captain Langdon charged Fireman F. Morant to break down the door, and head inside supported by his colleagues hauling the heavy hose behind him. The press reported – on his hands and knees he gallantly took in the nozzle and water was poured on the seat of the fire. As Morant’s efforts caused clouds of steam to add to the mayhem, Charles instructed his men to break down the shutters and introduce a second water stream from hose positioned in the street, enabling an air track that avoided poaching Fireman Morant. His tactics, for a man who had never been a fireman, were noted for their swiftness and success. The fire was got under within the room of origin.

When Ryde’s fifth annual Horse and Carriage show was held a month later, for the first time Sandown Fire Brigade attended with their engine under the command of Captain James Dore. Dore was known for many things, one of them being a keen networker. It is almost unthinkable that his brigade’s visit to Ryde wouldn’t have allowed him the opportunity to meet and discuss matters with his new contemporary in the town.

If they had, Captain Dore may have mentioned his intention to take a team of Sandown firemen to compete at the National Fire Brigades Union, Southern District drill competition at Southampton in July. It can be no coincidence that when an advertisement appeared in the IW County Press of 3 May 1890, marketing the sixth horse and carriage show to be held five days later, it included ‘Fire Brigade Competition on the Esplanade’. However, the competition was cancelled, largely due to the disinterest of Ryde’s firemen, although they had been happy to be seen parading in the procession. Charles had work to do to eradicate the apathy into which some of his firemen had slipped.

But an awkward distraction weighed on the captain’s shoulders.

On 4 August 1889, barely eight months into his captaincy, Ryde firemen, and others, had set about a rick fire at Stainers (a location close to Ryde House) under Charles’s instructions. At the Town Hall on 3 July 1890, an arbitration case relating to the incident, was heard between Mr Stainer and the Norwich Fire Insurance Company.

Today hay is baled and placed in barns. If a fire occurs the modern fire and rescue service will generally adopt ‘Mode Defensive’ and allow the fire to burn itself out, providing hose and water only to protect other property or assets by preventing fire spread. In the context of the period in question prior to the mechanisation of baling or rolling, ricks of hay were huge constructions. To all intents they were complete and densely packed temporary structures in their own right, featuring trusses, floor structure and a thatched roof. Constructing them was the work of skilled men. Losing them to fire would present a substantial if not ruinous financial cost to the owner, and a lack of vital supplies to the district. Protecting ricks was a serious undertaking of rural life.

Example of a rickyard located at Gosforth, near Newcastle. The large rectangular rick is provided with a vent built into the apex to prevent overheating leading to combustion.

The protracted report of 3 July hearing goes into great detail concerning the cross-questioning of witnesses without specifying the nature of the arbitration. Between the lines it seems apparent that the Norwich office were keen to wriggle out of fully compensating Mr Stainer, the Fire Brigade, and others, for the loss of the hay and the work undertaken to salvage what they could. In particular they were dissatisfied that they were liable for the loss of two adjacent ricks, initially unaffected by the fire, which became involved due to alleged mishandling of smouldering material cut away from the origin.

Throughout the course of the hearing, which took many days and several adjournments before its conclusion in mid-October, Charles was pulled to pieces by either side. He was questioned concerning his decision making, statements he made concerning decisions made and instructions given by others, including Mr Brooks the Borough Inspector of Nuisances and Mr Ratcliffe the local agent for the Norwich office, both of whom refuted Charles’s evidence in order to avoid any culpability. The scope and depth of the hearing, and the vast numbers of persons subpoenaed to give evidence, emphasises the critical value in late-Victorian society placed upon so basic a commodity.

All parties had to wait until early January 1891 for the concluding award of the umpire, Mr E.B. Squarey of Salisbury. His award was made in four parts. In the first Squarey agreed that the fire in the rick of origin was a matter of natural or spontaneous combustion. In the second, he determined that two other ricks – were damaged through protecting them against the said fire to the said large rick… and that the Society (Norwich) is liable and shall pay that sum to the said Daniel Stainer…

Reading the third part would have been tough for Charles to stomach – I do award, order, and determine that, from the evidence which has been brought before me by the said parties, the said Fire Brigade, in proceeding to extinguish and extinguishing the said fire and dealing with the salvage occasioned thereby as aforesaid, caused considerable unnecessary loss and damage to the unconsumed hay in the said large rick, and thereby greatly reduced the value of the salvage which might have been obtained by the said Daniel Stainer. However, Charles could take relief from the continuation of Squarey’s award – and that the said Fire Brigade were persons acting under the orders of the Society through its agents, and that the Society is liable to pay the said Daniel Stainer for such loss of salvage.

The award appeared in the IW County Press, not verbatim but as abridged by the editor for maximum sensationalism. Mr Stainer, in support of Charles and the Brigade (in addition to pointing out the failures of the arbitration system) felt compelled to write a letter to the IW Observer, published on 17 January – Allow me to apologise for troubling you again, but I think it only fair to the Ryde Fire Brigade, as the umpire’s award appears to throw all the blame for damage on them. That is not so. The greater part of the damage was done after the brigade had left. The umpire finds the company did take charge.

For Charles it concluded a testing first two years as Captain of Ryde Fire Brigade. For being nothing more than conscientious and exacting he had become an adversary of Alderman Dashwood and the Public Works Committee, his own firemen remained apathetic at his attempts to reinvigorate the brigade, and not only his decisions but even his integrity had been called into question during cross-examination in the arbitration hearing. Thankfully Mr Squarey’s perceptive nous favoured Charles’s testimony over that of Mr Ratcliffe, the local agent for the Norwich office – another potential enemy made.

On the same day that Stainer’s letter appeared in the press, Charles and the brigade were to inadvertently step into further controversy. A shop, store, and offices in Garfield Road were identified ablaze shortly before midnight. In time-honoured fashion, Supt. George Hinks of the Borough Police was on the scene before the brigade and acted with consequences. Hinks, for reasons known only to himself, attempted to access the burning property. On being beaten back by the heat and smoke he decided to clear the atmosphere by smashing the plate glass window. In rushed the air, and according to the correspondent of the IW Observer who witnessed the event – instantly there was an explosion.

Charles and the Brigade arrived on the scene and shipped a standpipe to the mains by 23:48, but no water emerged. Corporation officials stated this was due to freezing in the pipes. However, at 00:20 Charles took it on himself to go to the cock and try it - immediately water flowed into the system. By then the fire had taken a firm grip and it was with some determination and risk that the firemen waded into the mass and prevented the fire spreading further – Too much praise cannot be given to the Captain of the Fire Brigade and his men, who worked thoroughly well – summarised the Observer.

It was revealed in the following months council meeting that in an attempt to reduce water wastage, Corporation workmen were instructed to carry out repairs on the water mains by day and shut it off at night – but no one had considered advising Captain Langdon. Much shrugging of shoulders and finger pointing followed the excessive fire damage to the Garfield Road premises, which fortunately were fully insured and not subject to an arbitration case.

If there is one area in which a man can show leadership to his men, it’s in the case of their welfare and that of their families. In 1891 Ryde’s firemen were effectively volunteers although paid for their hours of work. No work at fires meant no pay.

The Corporation made no provision for their insurance in the event of injury or death, and not being members of the National Fire Brigades Union (yet), the brigade had no access to the Widows and Orphans Fund. When 33-year-old Fireman Frederick Thomas Passmore Jones suddenly died on 21 February 1891, Charles was quick to identify the plight of his widow Sarah Jane, and children Annie (12) and Frederick (9) by opening with his own money and arranging a subscription to support them.

Three months later the annual horse and carriage show was held. Again, the brigade failed to live up to Charles’s hopes for staging a drill competition. The local matter was exacerbated by the attendance of Shanklin Fire Brigade, formed only five years earlier, with their smart engine and well-equipped firemen, according to the IW Observer.

No doubt Charles began to consider his men’s reluctance and the reasons for it. The lack of any kind of insurance for the men had come to the forefront in the aftermath of Fireman Jones’s death, albeit there was no connection between his duties and his demise. In addition, they were put in the shade by Shanklin’s turnout in their own town’s horse and carriage procession. Charles decided it was time to go into battle for his brigade.

He submitted a letter to the Public Works Committee, by then chaired by Mr Riddett, although Alderman Dashwood remained a member. In reading the letter Mr Riddett recommended to the committee members that it be agreed. Charles wrote an appeal rather than a demand – I now beg to ask you if you will equip the members of the brigade that they may be able to discharge their duties with as little risk as a fireman can expect. You are doubtless aware that the brigade consists of fifteen firemen and myself. They all have very good helmets and a loose serge jacket, and six have belt and axe. The serge jackets are not waterproof, and at fires since I have been appointed it has been necessary to send two or three home immediately the fire was got under. The men show a great interest in the brigade… some have started a boot club and obtained top boots, for as you know it is impossible to keep a dry foot at a fire in ordinary boots. I have not officially applied to you before, knowing the large expenditure for appliances which I have recommended, the amounts for which I am pleased to say you have always granted me, and I trust you will now equip the men as follows.

15 waterproof tunics

15 pairs trousers

15 pairs top boots

15 brass numbers

9 axes and belts with lifelines

6 lifelines for present belts

The estimated cost of which is from £55 to £60.

I also beg to ask you to consider the desirability of insuring the members of the brigade against accident and death, whilst performing a duty so dangerous to life and limb, and to point out to you that a large number of brigades are insured, some of which belong to considerably smaller boroughs than ours. I enclose you a prospectus showing that the brigade can be insured at the small premium of about £3 10s.

I am Gentlemen, your obedient servant, Charles Langdon.

The letter reached sympathetic ears, with supportive remarks from all sides of the chamber bar one, Alderman Dashwood. What motivated Dashwood, a long-time supporter of the brigade during the majority of Henry Buckett’s tenure, to suddenly flip to the negative is difficult to define. I am always sorry to have to object to any recommendation that came from a committee of which I am a member. Why should we tie our hands in the matter, when there is no greater emergency in the matter now than there has been for the past 20 years? I do not say that a man could extinguish a fire more expeditiously and effectually with a pair of top boots and an umbrella than with ordinary attire, but we have not got the money. I condemn the system by which improvements are carried out which were not included in the estimates.

Mr Ellery spoke next, taking the Alderman to task for introducing umbrellas into the equation – Reorganisation of the brigade and appliances has never been gone into in a proper manner. We have never properly fitted them out for cases of emergency as it is our duty to do. Umbrellas were not included in the list, and the fire brigade men would not shrink from getting wet if there was any probability of saving property from ruination. I can hardly realise a brigade without axes, belts, and lifelines, if I had not seen it in my native town. By complying with the request we would encourage the men, who devote a great deal of time for little remuneration to look as smart as their neighbours who we have lately seen at the show.

Alderman Marvin was succinct – The brigade risk their health and lives when called out and the Council should give them every encouragement and support… boots, lifelines and belts were really necessary articles.

Mr Flux, who owned the Garfield Road property attended by the brigade in January, being one of those committee members who failed to consider advising Captain Langdon of the water being shut off, expressed appreciation for their work, adding - It is the duty of the Corporation to place such equipment in their hands that they can perform their duties with the least possible risk to their health.

Before the recommendation went to the vote, the Chairman had the final say – We are rather behind the times in Ryde in this respect. I think it very desirable to provide the brigade with suitable clothing. The men cannot afford to have a suit of clothes spoiled, however poor it might be, at every fire they attend. I know there are ratepayers outside who are warm-hearted enough to say they will collect money for providing the equipment if the Corporation does not do so, but I think it the duty of the Corporation to provide it.

At the vote, adoption of Charles’s requests was agreed by 15 votes to 1 – the one being Ald. Dashwood.

Later in the year the Brigstocke Almshouses opened in Player Street. Principal architect and builder was Charles Langdon. It was highlighted in the press report that, combining his building acumen with his expanding knowledge of structural fires, the construction was afforded stone staircases as a fire safety measure.

A typically accoutred Victorian fireman, as depicted in a contemporary advertisement.

In 1870 Charles’s predecessor Henry Buckett earned the respect of the town for his decisive action at the George Street Congregational Church fire that many feared would spread throughout the entire block. That fire was referred to in the IW Observer when reporting a fire that occurred in the High Street in the early hours of Saturday 13 February 1892.

On Saturday morning, the most serious fire which has occurred in Ryde, since the George Street chapel was burned down, occurred in High Street, and resulted in the destruction of the Liberal Club.

Although the fire broke through into a neighbouring workshop, Charles sent his firemen in to the thick of the smoke in a three-point attack from the side, the back and a staircase leading off the High Street. A protracted period of firefighting in dire conditions ensued, requiring the rotation of those in the smoke with those on external branches to allow a degree of recovery following bouts of unavoidable smoke inhalation.

Despite their efforts substantial damage was caused, compelling the Observer to include in its report – In the opinion of some who were early at the fire the disaster has demonstrated the necessity for a change in the Fire Brigade arrangements. They think the hose, fire escape, &c., ought now to be kept at the Police Station instead of the Town Hall. At the Police Station there is always someone on the alert… It is also suggested that an extra bonus might be given to those firemen living in the immediate neighbourhood of Brunswick Street, so that they might be called out immediately. We also hear that the new hose did not answer very well. Some of the lengths did not join properly, and when it was desired to lengthen one portion, it could not be done.

Given their efforts the Brigade may have been miffed by the tone of the report that offered no appreciation. However, Mr J. Watkins, whose business suffered damage in the fire, but whose residential quarters was saved, bypassed local press, and submitted a letter to the Portsmouth Evening News which may have encouraged the firemen – I shall be glad to avail myself of your space to acknowledge the skill and promptitude with which the Ryde Fire Brigade under their captain, acted on Saturday last. The fact that so serious a conflagration was confined to one part of my premises, and that I was enabled to open my shop in a few hours, as soon as the assurance company’s consent was wired, speaks for itself. I thank the Brigade, through you, most heartily for their services.

Charles’s aspiration to hold a fire brigade drill competition over the previous two years had involved the contribution of finances from local fire insurance offices. Charles provided receipts and as accorded by the Council, forwarded the funds to the Corporation for accounting purposes. When it emerged in April 1892 that a deficit was present in the account, Charles didn’t refrain from asking the difficult question it posed.

‘I collected from my own office’, stated Charles, ‘they (the insurance offices) will want to know what has been done with the money.’

The Secretary rebuffed with avoidance tactics, ‘There was no fire brigade competition because your men objected to compete.’

‘It does not matter about my men’ Charles retorted.

‘It was two years ago,’ continued the Secretary.

‘That does not matter either. If the money was collected for a special object it ought to have been kept for that object. I ask you what you have done with it?’

The Mayor intervened, ‘The money was accounted for two years ago.’

‘Then you have got it in hand?’ Charles’s statement was more question requiring confirmation.

‘No’ replied the Mayor, ‘it was swallowed up in the Horse and Carriage show’.

Charles was furious, ‘What am I to write and tell my people – that the money is still in hand, or that the money has been spent for another object?’

‘We have never been able to spend the money because we could not get up a competition,’ said the Secretary, adding, ‘it has gone into the general fund’.

At the point that Captain Langdon was possibly ready to explode, Mr Fowler mitigated, ‘We should make it clear that we are prepared to carry out the fire brigade competition as soon as he can get men willing to compete. I quite understand Mr Langdon’s position.’

In the following month at the recommendation of the Public Works Committee, Council ratified an agreement to insure the members of the brigade against accidents at a cost of £3 6s per annum with full benefits.

Carisbrooke, circa 1900, the Eight Bells at the far right, the final destination for many an annual excursion of Ryde's firemen and police.

During the reign of Charles’s predecessor, relations between the Borough Constabulary and the Fire Brigade had sunk to their lowest point, the catalyst having been the notorious controversy of Dr Hasting’s Cat in 1882. Since his appointment as captain, Charles had worked hard to repair the damage and establish a healthy and positive working relationship with the force. His efforts came to fruition in mid-July 1892 when for the first time in over a decade the firemen and policemen shared an outing. Evidence of the esteem in which they were held by local residents is that the trip, held twice four days apart to ensure a contingent of both services remained in the town, was entirely funded by public subscription. The successful excursions to Freshwater were the first of many and established the custom that no matter where they had been, including mainland visits, the tour concluded with an exuberant drinking and sing-song session at the Eight Bells in Carisbrooke before the last leg to Lind Street.

When the IW Observer erroneously reported that Alderman Dashwood had attended the trips, he responded to the newspaper offices angrily, compelling their retraction in the next edition, to which they added – As a matter of fact, we understand Mr James Dashwood disapproves of members of the Council taking part in an excursion which was provided for our borough officials by public subscription. As the members of the Council, we understand, very liberally contributed from their own pockets to the enjoyment of their employees, this has been regarded as hyper sensitiveness on the worthy alderman’s part.

On 23 December Ryde’s firemen and captain received an urgent and unusual request – to attend a fire in Shanklin. On arrival they found the brigades of Ventnor and Sandown already alongside that of Shanklin, attending a blaze originating in a High Street ironmongery operated by one Mr Daws.

The fire was so great, the challenge of fighting it so hazardous, and the potential loss to a substantial proportion of the town so feared, that the date became an anchor in time and for many years afterwards Shanklin residents referred to memorable events as occurring before Daws or after Daws. The outstanding heroes of the hour were Captain Dore and the Sandown men, who amid the heat and smoke, entered the first floor and carried out a safe containing 90lbs of gunpowder disregarding their own safety to ensure a potentially devastating explosion didn’t occur. When Ryde’s councillors next met on 10 January, the Town Clerk read a letter received from his Shanklin counterpart remarking on the zeal and energy of Captain Langdon and his firemen.

Charles remained committed to organising a brigade drill competition. It was true that his firemen had lacked interest in previous years, but that wasn’t the case in 1893. Charles submitted an open letter to the Observer stating that his reason for again cancelling the event, was because the public had so many calls upon them recently that he felt it inadvisable to make yet another demand on their kindness. He closed with – We hope to revive the proposal next year and to be able at once to benefit a very important branch of the public service and to swell the funds of a valuable Island Institution.

Determined to achieve his goal, he invited the captains of brigades across the Island to attend a meeting at the Town Hall on 31 March 1894. This meeting was a critically important milestone in the history of IW firefighting. Not only did the captains collectively agree on a competition date and plan, but they also founded the Isle of Wight Fire Brigades Association (renamed Federation two years later).

Six weeks later Ryde Fire Brigade were second only to the marching band of the Rifle Volunteers in the procession that marked the annual Horse and Carriage Show, resplendent in full uniforms – gleaming brass helmets, serge blue tunics bearing brass numbers on the left breast, matching trousers, belts from which were suspended tightly knotted lifelines and sharpened axes, and keenly glossed top boots. Smartly and in time to rousing military compositions they swung their arms, stepped out and swaggered along the Esplanade.

Charles Langdon’s plan for the promotion and betterment of Ryde Fire Brigade was, against all the odds and a host of critics, finally coming together.

The first competition of the IWFBA (F) was held at Simeon Street Recreation Ground on Thursday 6 September, the same day as Ryde Carnival. Organised by Charles, assisted by Mr Groves, Chairman of the Public Works Department, the event kicked off with a parade in Lind Street, formed of the brigades of Ryde, Newport, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor. With the Band of the Rifle Volunteers at the head, the procession snaked its way through the town’s principal streets before arriving at the venue having collected a fair crowd along the way.

The competition featured six categories, four of them conventional drills, then a hose race, all of which were judged by an Engineer Penfold of the Metropolitan Fire Brigade.

An Ambulance Drill open only to those men that held a St Johns certificate was judged by Dr J.D. Davis of Ryde. The competitive element ended with a rowdy tug-of-war competition won by a combined team from Newport and Cowes and the event closed after a massed display of fire extinguishing.

Colourised image of the group photo taken when the IWFBF drill competitions returned to Simeon Street, Ryde, in 1903. The quality of the original print, owned by Charles's great grandson David, is so great that an electronic scan allows for clear identification of individual faces when zooming in (resolution reduced for website upload).

The list of attending dignitaries was long and included Alderman Dashwood. Among the substantial list of benefactors that donated trophies and prizes were Mr Ratcliffe, local agent for the Norwich insurance office - both matters suggesting that Charles’ affable nature was capable of reforming good relations with former adversaries.

In the immediate aftermath the Carnival Committee were so enthused by the event and its fascinating new edge to the town’s big day, that on finalising the accounts the outstanding balance was forwarded to the IWFBA on condition that another competition was held the following year.

Although not listed in attendance, news of the event must have reached Prince Henry of Battenburg, husband of Queen Victoria’s youngest child Beatrice, and Governor of the Isle of Wight since 1889. Similar to many notables among nobility of the time, the Prince was fascinated by the concept of firefighting being delivered as a sporting event. On 17 August 1895 the IW Observer revealed that the Prince had donated a trophy, to be known formally as the IWFBA Challenge Cup, but became known colloquially as the Battenburg Cup. Given the noble status of its benefactor, the cup, though modest in appearance, was immediately promoted to the fore to be awarded to the winners of the annual Officer-and-four-men drill competition – the finale event.

Despite the 1894 agreement to again coincide with Ryde Carnival, the 1895 event held on 28 August, with the Battenburg Cup taking pride of place on the trophy table, was competed for at Shanklin’s County Ground for reasons not known. It was another major success, administered by Charles, with the finale drill evidencing a keen edge as each brigade vied to be the first holders of the distinguished new trophy. Cowes Fire Brigade, commanded by Captain Ernest Willsteed, who had won the same event in 1894, managed to repeat the effort with the same team, Foreman Thomas Richardson with firemen Harvey, Ford, Varney, and Moore, and claim the new award. Notable in the IW County Press report, is that Ryde Fire Brigade attended under the captaincy of Herbert Vale Carter.

Charles had resigned from the fire brigade by letter dated 20 June. The content of the letter is not known, but the content of its acceptance, in the form of a letter dated 6 July, written by the Town Clerk, is – I am instructed to say (by the Public Works Committee) that while accepting your resignation they regret you should feel obliged to take this step and further to say how much indebted the Town is to you for all the time and attendance you have bestowed on the Brigade and for the valuable services rendered by you as superintendent during your term of Office.

In Council three days later the matter of Charles’s resignation was briefly raised. Alderman Marvin revealed that Charles had approached the Public Works Committee for expenditure for a few new lengths of hose – and he was refused, and he could not do less than send in his resignation. It showed want of confidence in the captain of the Fire Brigade. Mr Ellery was of similar mind – He had got beaten on the vote of supply and did what other gentlemen had done… Mr Groves retorted that a letter had come before the Committee requesting two or three more lengths of hose, but not the reason why.

For the sake of positive communication from the committee and a nominal cost of two or three lengths of hose, Charles felt undermined and compelled to resign. I am tended to think there was more to the stance of the committee than the simple matter of a need for hose and that Charles’s ultimate abdication was engineered.

Despite playing no further active role in the brigade Charles remained at the forefront of the Isle of Wight Fire Brigades Federation until 1899. When rescinding his IWFBF role, Charles was to remain at the forefront of life in the town and remained so throughout his life, making countless contributions both in his profession and public office.

Tragically Charles and his wife Annie were to learn of the death of their 30-year-old son, Lieut. Arthur Charles Langdon, 7th Hampshire Regiment, which occurred less than three weeks before Armistice Day 1918. In a letter received from Major George F. Schwerdt in early November, were the words – It is with the greatest sorrow that I write to tell you of your son’s death. He rushed a German post in a farm, got wounded and surrounded and was hidden by the civilians. There he was for three hours before the battalion captured the farm and found him. His action was splendid, and he was put in for the Military Cross. You have the sympathy of all the battalion and his many friends. Lieut. Langdon was buried and remembered at the Moorseele Military Cemetery in West Vlaanderen, Belgium.

The IWFBF went into decline prior to and during the terrible years of the First World War, and didn’t fully revive with any purposeful intent until the mid-1920’s. In 1929 Charles donated his own cup to the Federation competition committee. Engraved for the Escape Competition, it was also used in the 1930’s as the prize for the winning team of the motor turnout drill. In 1935, at the invite of the IWFBF committee that he had created over 40-years earlier, Charles accepted the role of President of the Federation.

Incredibly, in his 80’s, Charles volunteered for a role with the Air Raid Precautions (Civil Defence) service of the Second World War. It is believed that it was in this capacity that he was harmed during one of the aerial attacks on the town, from which he never recovered.

Charles passed away on 25 January 1944 at his home, 13 Melville Street.

In eulogy the IW County Press published the following – A son of the late Mr John Langdon, he succeeded his father and grandfather in the business of builders and undertakers, one of the best known in the Island. He also succeeded both as steward of the Brigstocke estate and all his activities were characterised by quiet efficiency and unfailing business acumen. He was a man of outstanding activity, which even advancing years failed to diminish and his sprightly figure was a very familiar one in the Borough. He took a very prominent part in the governing and social life of the town… As a member of the old IW Volunteers he became a good marksman and won many cups and spoons. He served a period on the Town Council until his defeat at the election after the last war. Under his direction many well known residencies have been built… He was director of the Ryde Gaslight Company. His social activities were of a varied nature.

Charles's Second World War Chillington ARPAX.

His passing leaves the town poorer, for he was always jealous for its welfare and contributed in no small measure to its wellbeing during a long and useful career.

Discovering the story of Charles Langdon, and particularly his substantial contribution to the development of IW firefighting by creation of the IWFBF, was a key factor that altered the course of my research – from that of Ryde Fire Brigade in isolation, to that of all Isle of Wight firefighters. This was not so much a conscious decision, but a natural evolution influenced, over one-hundred years later, by what Charles had achieved in the 1890’s. Such was his leadership quality that the influence of his legacy led me down many fascinating paths of research and discovery that might otherwise have been missed.

Charles Langdon was without a doubt, both within and without IW firefighting, a leader.