In late 1892 the men of Newport Fire Brigade were incensed that their captain had received a pay rise that in terms of percentage substantially dwarfed their own and launched into a pay dispute with the Corporation.

Led by Deputy Captain and brigade Engineer Jacob Peach supported by long-standing firemen Obediah Jackman and John Stubbs, the firemen stood together. After having their demand snubbed by the councillors the leaders of the dispute pledged that if the council didn’t listen and act on their demands the entire membership would resign on 23 February 1893. The councillors rejected the plea totally and called their bluff.

Corporation wheels went into overdrive to recruit a batch of replacement firemen ready to take over on the fateful date. The situation inspired the councillors to have a rethink, and the decision was taken that paying firemen wrought trouble – the new brigade would be known as the Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade, and its volunteers wouldn’t be paid a penny.

By arrangement with the Metropolitan Fire Brigade an experienced instructor was hired. John Shaw was a favourite of the Metropolitan service, a fireman of 30-years’ experience, twice commended and medalled with clasps with a record of 17 lives saved from fires and one from drowning. Shaw hastened to the Island to deliver ten days training to the twenty-one rapidly assembled volunteers of the brigade in waiting.

Among the volunteers was Nicholas Henry Thomas Mursell. The volunteers, following the pattern successfully adopted at Sandown, were permitted to elect a Captain from within. They selected Percy Shepard. For reasons unrecorded Shepard submitted his resignation effective 28 December 1894. By the time of Shepard’s departure only seven of the original 21 remained, including Nicholas Mursell. In preparation for Shepard’s resignation Mursell, who had taken the lead in 20 of the 30 drill sessions completed over the previous year, was appointed pro tem captain until the next brigade annual meeting.

In August of the same year his men expressed their appreciation of his efforts by collectively subscribing to present him with a plated cross-belt and pouch. Nicholas’s permanence was assured by his cool leadership at fire incidents over the course of the year and was formally confirmed by the Mayor, Alderman Francis Pittis, at the brigade meeting of 30 September (the mayor was also the superintendent of the brigade but in an honorary capacity only). The Mayor also spoke favourably of Mursell and the Brigade at the AGM of Newport Town Council on 9 November – Their popular captain Mr Mursell is doing everything he can to improve the brigade. This included not only some notable wins at IWFBF drill competitions, but also the despatching of a team to perform in a regional event at Brighton.

In the December, as promised by the Corporation, the halls of the old marketplace beneath the Guildhall were cleared out and Nicholas was handed the keys. He and his firemen spent their own time, without pay, carrying out alterations to accommodate the engines and equipment, and the town’s new fire station was soon in operation. No doubt the Castle Inn on the High Street became a fixture of the firemen’s social life as Nicholas was the licensee. In the 1890’s his tenure at the Castle was in its early days but was to extend to more than fifty years.

In the following June, after the brigade had faced some challenging fires since the New Year, Nicholas and his men organised a day of sports and drill competitions to be held in a field to the rear of Polars, Staplers Road. Although other seasonal attractions were cited as the cause for a lower attendance than anticipated, approximately 500 persons passed through the gates to participate in the festivities. The Band of the Rifle Volunteers provided a musical accompaniment to seven competitions, comprising several heats, in addition to lighter entertainments such as the tilt-the-bucket competition and Fireman John Ambrose Garraway’s clowning around in suitable attire.

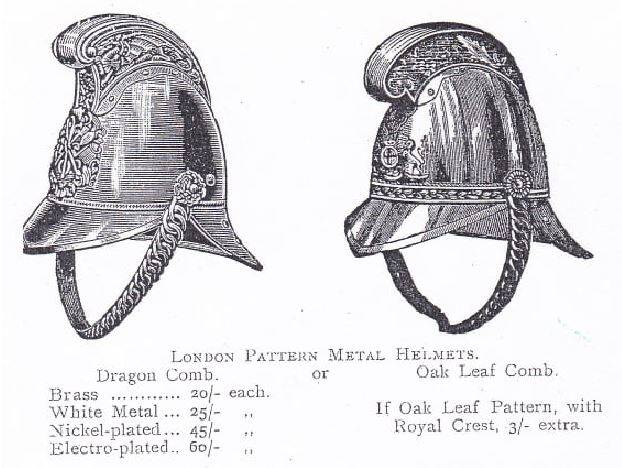

Throughout the remainder of the 1890’s and into the early years of the next century Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade were to attend a wide variety of quite challenging fires at a rate above any other single district of the Island. Despite continually performing striving to do their best and saving a multitude of stock and property from destruction, it became apparent that the Corporations’ enthusiasm for its brigade was waning. By 1903, Newport’s firemen were the sole brigade still wearing black leather helmets – all others sported the iconic brass type. On 26 April 1903, during the middle of three-days of the NFBU/IWFBF combined camp and drill competitions in Ryde, the massed brigades formed up at Holy Trinity Church in Dover Street for church parade.

Re-emerging into the street after the service, master of ceremonies Captain James Dore of Sandown Fire Brigade was organising each brigade into its allotted place in the procession and hollered – Black helmets to the rear – a slight on the Newport firemen’s headgear. This caused a ripple of titters throughout the ranks of brass helmets from within which Newport’s firemen had also been labelled the black rooks. In the end the Newport firemen had the last laugh by winning the Battenburg Cup the next day, but the Dover Street event compelled an anonymous Newport fireman, who signed his letter One of the Rooks, to submit his displeasure for publication in the following weeks IW County Press. Although the writer used some mirth to emphasise his point, he, and his colleagues, were clearly dissatisfied at being left behind in this context.

Two weeks later the matter was raised in Council. The men of the chamber satisfied themselves that there was no need to afford such luxuries on the justification that black helmets made it easier to identify the men from the officers at fires.

On 4 August the General Purposes Committee allocated £45 expenditure in respect of a new wheeled escape ladder, after 18-months of Mursell telling them the old escape ladder was dangerously decrepit.

By October nothing had been done about the ladder. In frustration Captain Mursell by-passed council, in which he was an elected member of a ward and made direct contact with Merryweather’s. Armed with the quote for the ladder he approached council. Such was the general rejection of his doing so that he expressed how frustrated both he and his firemen were that no improvements were ever concluded. The General Purposes Committee backtracked, talking of obtaining further quotes before being harangued into deciding. Whilst Alderman Cheverton spoke strongly in favour of accepting the captain’s professional judgement, the Mayor made light of the firemen’s lot by reference to the pay dispute debacle of 1893, suggesting sarcastically to Mursell ‘so we must, or you’ll resign?’ How Captain Mursell walked away from the meeting without losing his rag, and his position, is a remarkable display of self-control.

Nicholas wouldn’t give up for his firemen. It’s arguable he abused his council position as representative of a ward in arguing for the brigade, but without that level of access progress would have been nigh on impossible. By his available means he was finally able to secure his men their much longed for brass helmets in April 1904. It was one small victory in an era where no legislative imposition existed to compel local authorities to provide for firefighting at all – victories, where they existed, were wholly down to the tenacity of officers in charge of brigades.

Four years later a fire of substantial proportion emphasised the inadequacy of the brigade’s equipment. Jordan and Stanley’s Nodehill store was all but levelled by an early morning blaze estimated to have caused £7,000 worth of damage – an incredible sum of loss for the time. Chief Officer Mursell (use of ‘captain’ being superseded) quickly identified that the fire was beyond the capability of his manual engine and hose cart. Matters worsened when partial collapse of the store frontage buried the latter. Mursell despatched an early message to Shanklin, one of two brigades that had acquired the island’s first steam fire engines in the previous year. To their credit the Shanklin brigade deployed its steamer, with full crew all up, and arrived at Nodehill in 35 minutes – according to the IW County Press. The incomparable water flow thrown from the Merryweather Gem enabled the men of Newport and Shanklin to prevent fire spread beyond the building of origin – but the Jordan and Stanley’s store was lost.

In the aftermath messages of appreciation and admiration for the steamer and the firemen’s skills in the use of it were sent to Chief Officer Rayner at Shanklin from the owners of the store, plus the Clerk of Newport Town Council, and the Mayor. But the latter pair never stopped to consider that their own Borough might benefit from an improved firefighting capability of their own. However, the Corporation made one substantial strategic change to the brigade later the same year. The move was not one of brigade improvement but driven by a desire to shut Mursell and his firemen up.

A report appeared in the IW County Press following a Council meeting, including the statement – To reconstitute the Volunteer Fire Brigade as a paid Brigade is a step in the right direction, as whilst such recognition is due to the firemen, it will ensure that full public control which is practically universal in this important branch of the public service. The town will forever be indebted to the Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade for stepping into the breach at a time of emergency and evidencing truest patriotism in the interests of the old borough and its inhabitants.

The truth behind the public flannel was that the Corporation wanted paid men because they perceived that paid men can be controlled, ordered, and silenced. It wasn’t lost on the firemen of Newport that in the same week the Council made the announcement, the fledgling brigade at East Cowes was already ahead of the game, ordering a Merryweather Gem steam fire-engine. Chief Officer Mursell emphasised this during his speech at the Brigade’s annual outing two days later – the fire at Messrs. Jordan and Stanley’s showed the need of a steamer. I am pleased to see that our past services have been recognised in the County Press, but I had hoped to have seen it in the form of a vote of thanks at the meeting of the Town Council. I ask you to drink to the success of the new brigade.

The Corporation issued a full set of new brigade rules, an original copy of which is held at Carisbrooke Castle Museum. In it the Corporation removed the Chief Officer’s right to autonomously appoint new firemen or promote existing members without agreement from the Corporation. By then many of the volunteer firemen had already submitted their resignations, effective on 24 November.

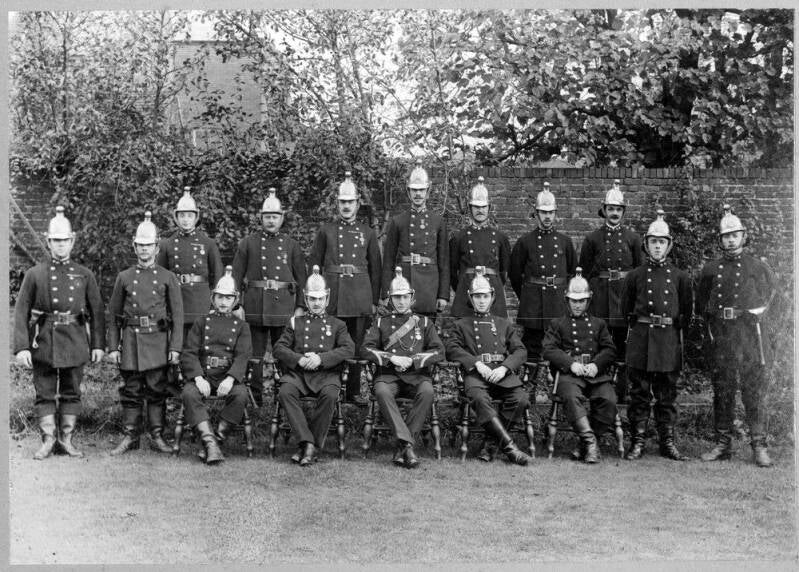

Chief Officer Mursell, far right, his firemen and the Newport manual engine, which is today on display at the fire service training centre in Ryde (read it's story HERE).

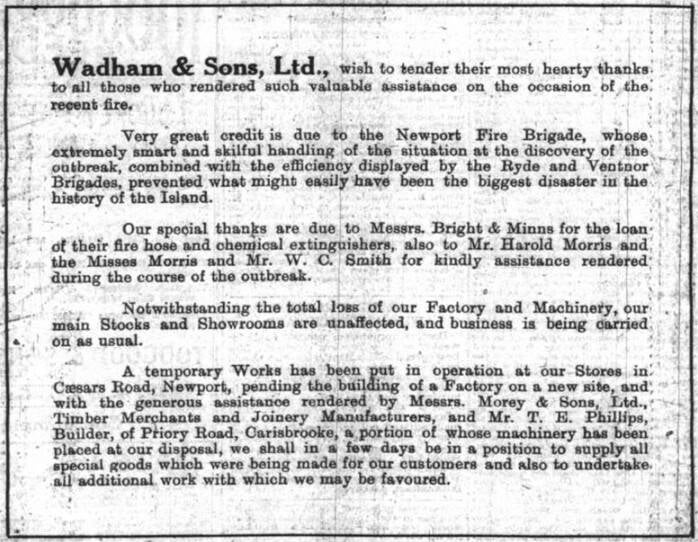

Advertisement for firemen to fill the remodelled 'paid brigade'.

Feelings must have cut deep for men to leave as the rules also detailed the rates of pay – three shillings for the first hour and one shilling sixpence for ever hour thereafter, plus paid cleaning time, out of pocket expenses and the creation of a contingency fund to assist firemen and or their families in the event of hardship. In order to replace those unwilling to remain, some of whom the Corporation didn’t want anyway, an advertisement was placed in the County Press. When news spread of the associated pay arrangements, a significant number of applications arrived on the Town Clerks desk.

In the next edition of the County Press an article was afforded to the feelings of volunteer fireman G. Scott, who had evidently applied for one of the paid roles – the great injustice inflicted on myself and some of the members of the Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade in being refused admission to the newly-constituted Fire Brigade. I feel sure that some undue influence has been brought to bear…

No doubt Nicholas would have fought the decisions with his noted mettle were it not for the fact that his priority was his wife Kate’s declining health, leading to her premature death aged 47 in the following July. It may have been of some solace that later in 1909 the Chief’s 21-year-old son Leonard joined him in the ranks of the paid fire brigade. Twelve months after Kate’s death Nicholas remarried, to Edith Maud Ireland in Richmond, Surrey. After honeymooning in Paris, the couple returned to the Isle of Wight and Nicholas remained the landlord of the Castle Inn.

In his brigade duties Nicholas was ably assisted by a newly appointed Second Officer Alfred James Whittington. Although the Corporation repeatedly resisted efforts from the officers to force change in the shape of a steam fire-engine, the brigade did expand by adding a second manual engine capability. This allowed portions of the brigade to respond to a far wider area, where fire insurance policy was agreed, provided that a contingent and engine remained in the town for local fires. With the capable Whittington at his side, the two men managed the divisions capably to meet the requirement. This not only added to the Newport brigade’s reputation, but it also vastly increased the earning opportunities for the firemen.

Everything seemed settled and working well for the future of the paid Newport Fire Brigade, until the opening of the First World War. Immediately Whittington departed to extend his concurrent role as Lance Corporal of the Isle of Wight Rifles – he was dead within a year, one of 89 killed amid the dust of Suvla Bay, his last resting place remains unknown. The needs of the war drew so many from the ranks of the brigade that by February 1915 the Borough’s General Purposes Committee requested, and were granted, permission to recruit a Voluntary Honorary Fire Brigade to act as an auxiliary to the remnants of the regular brigade. The Corporation decided that those recruited were not in need of firefighting uniforms or helmets. Among the unclad were several elder members of the 1908 volunteer brigade who had been refused, or had not wished to join the paid brigade.

In May 1915 Nicholas was awarded his 20-year silver NFBU long service medal in a ceremony alongside several others with lesser awards, but the mood of the moment allowed for little celebration. The IW County Press article concerning the event lists several of those receiving their 10-year medals as preparing to mobilise for the front and that six were already gone.

Chief Officer Mursell could do little to help his mobilised firemen directly. He did however ensure the safety and security of their families. Additionally, he enthused his remaining firemen to contribute to simple gifts of tobacco and sundries of great value and luxury on the front line, that were despatched to their absent friends in foreign fields. Among the appreciative who wrote back was Lance Corporal H. Perkins, whose story of wounding and survival is worthy of a feature in its own right. Writing from hospital in Manchester he thanked the brigade for the tobacco and shaving materials before revealing – I am sorry to tell you that my Fire Brigade work is finished, as, after all the care, kindness, and the best of treatment, there is only one thing to save my life, and that is to have my leg off. I stood for my country in her hour of need, and I hope and trust, if I recover from my illness, that my country will stand by me. Perkins, formerly a renowned footballer of Newport FC, survived the operation and was returned home in February 1916.

The war took its toll on all, Newport Fire Brigade were to lose several, but were later rejoined by some – men shattered by their experiences who somehow maintained the wherewithal to return to the Borough and their roles protecting its persons and property from danger of a domestic nature.

During the war years the IWFBF went into virtual abeyance. More of its membership were serving overseas than remained at home. Post-war there seemed little appetite until March 1920 when Nicholas was voted to return to the chair. But progress was slow in the post-war aftermath, a time of tough economy. Newport’s Corporation had rarely invested significantly in the brigade and the time wasn’t conducive to change.

The era of the motor fire engine was gathering pace on the mainland, even so it was perhaps with hope more than belief that Nicholas invited a delegation from Leyland to come to the Island in April 1923 and demonstrate their latest appliance which attracted an approximate £1,500 price tag. By this stage it was incredible that the County town brigade were still responding to fires with a manual engine – all other major brigades on the Island had been equipped with a steam fire engine since before the war. In the aftermath it was the visitors from Ventnor that were sufficiently impressed and funded to invest in the new machine, becoming the first IW brigade to evolve into motorised firefighting later the same year.

Nicholas plugged away at his council but without result. His work as chairman of the IWFBF resulted in more positive outcomes. A major resurrection of the Federation occurred in March 1924 under his direction and led to a drill competition in combination with the Southern District of the National Fire Brigades Association in June. Although the event was hosted by Sandown, and largely organised by their Chief Officer Billups, it proved a resurgence of interest in the IWFBF that hadn’t held its own event since before the war. Although there wasn’t another IWFBF competition for two years, it was the start of a pattern that remained a fixture in IW firefighting until compelled to cease due to the demands of the Second World War.

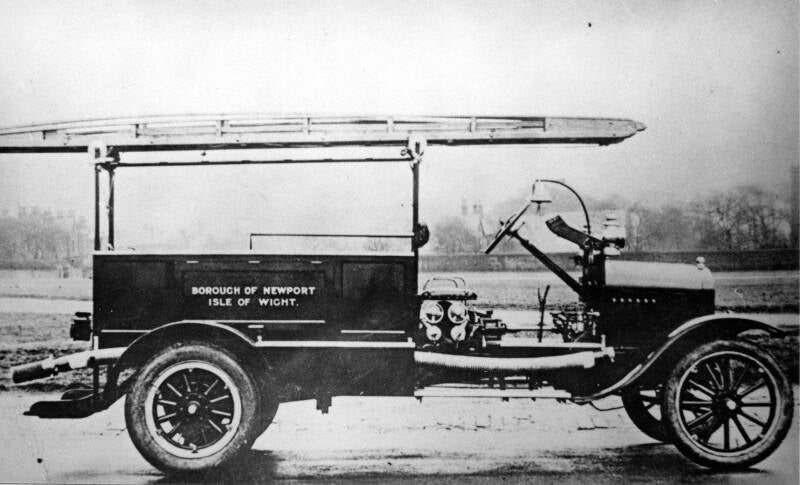

Newport Fire Brigade's Ford Stanley motor fire engine.

When Nicholas finally convinced the Corporation that the town required a motor fire engine, they opted for a comparatively feeble Ford Stanley adaptation. Placed against the range of more powerful and robust engines sported by Ryde, Sandown and Ventnor, the Ford Stanley became a source of humiliation for the firemen in a manner not dissimilar to that experienced during the period of the black rooks helmet issue. Nevertheless, the brigade finally had powered wheels. Oddly Newport completely missed the steam period going straight from manual power to motor. In July 1927 Nicholas’ next battle was against the Corporation’s intent to reduce his manpower. Justification was based on a council assumption that a motor engine required less firefighters, but the argument they offered listed only the cost benefit of a lesser workforce.

Chief Officer Mursell’s case against the reduction was prescient when considering the needs of a notable fire in the town centre three months later, 4 October 1927. This incident, more than any other, evidenced the Chief’s command prowess in a manner, and at a speed, never seen before on the Isle of Wight, and represents the primary reason for my inclusion of him in this series of Leaders articles.

The incident inspired the IW County Press to fill a lengthy article, beginning with the following – The fire which broke out on Tuesday night at Messrs. Wadham and Sons’ furniture workshop, behind their premises in the market at Newport, might easily have resulted in the destruction of the greater part of the whole central block of business premises in the heart of the town bounded by St James’s and St Thomas’s squares, High Street, and Pyle Street.

Two views of the Wadhams store frontage from either end of St James's Square.

This was to prove the most threatening fire since the Great Fire of Newport of 13 November 1785, when seventeen buildings were destroyed, and two lives lost. That occurrence was engaged by a gathering of willing townsfolk under the direction of the overseers of the poor armed with the most basic of manual fire engines and no mains water system. In 1927 Chief Officer Mursell was experienced, leading well drilled firemen equipped with a modest but efficient motor fire engine drawing water from a plentiful main.

The building of origin was described as the old tannery located within the square space between the buildings that fronted the block on all sides, several of which were structurally abutted. One building not joined was Unity Hall, a six-foot passageway separating the two structures to the rear. Inside a committee meeting of the Victoria Sports Club was taking place. The attention of the committee members was distracted from sport by the sound of crackling, rapidly followed by an orange glare in the rear windows.

Newport Fire Brigade, circa 1925.

Coincidentally the members of the fire brigade were just leaving St Thomas’s having participated in a procession following a service of hallowing. As the committee members burst from the front of Unity Hall in an excitable state the firemen received the news and ploughed in, with the appliance driver dashing the short distance to the Guildhall to bring the Ford Stanley to the front of the Hall.

Chief Officer Mursell’s first impression of the situation was met by a view described in the County Press – the huge mass of flame proceeding from every portion of the building shot quite 50ft., into the air, showers of sparks flew in all directions threatening to ignite surrounding buildings, and the glare of the conflagration lit up the whole town and could be seen from distant parts of the Island.

It was distant parts of the Island to which the Chiefs first thoughts were directed. He tasked a policeman with making calls requesting assistance to the brigades of Ryde, Sandown, Shanklin and Ventnor. As Mursell’s men pressed into the torrid smoke-logged passageway, armed with a charged hose in an attempt to separate the flames from the rear of Unity Hall where the glazing was already cracking, the wheels of motor engines to the east were already thundering to the Island’s centre. Inside Unity Hall an army of helpers began removing furniture and valuables to St Thomas’s Square where a large crowd had gathered.

With conditions in the passageway deteriorating the firemen, some of them insufficiently protected with basic respirators and others with no protection at all, rotated to the branch for as long as they could withstand the punishment. Concerned for their safety Mursell deployed a second hose to run in through the doors of Unity Hall to the back of the building where a shattered window allowed his men to jet water directly into the burning mass with a substantial improvement in their own safety. The passageway attack was abandoned.

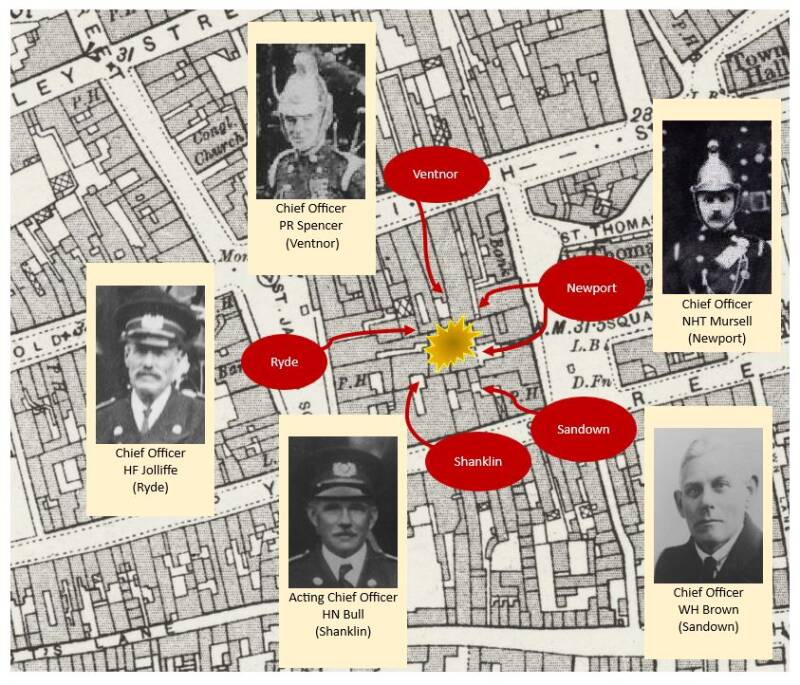

In the time it took for the initial firefighting to be undertaken, withdrawn from and the revised plan put in place, Chief Officer Mursell was suddenly, and much quicker than he estimated, besieged with appliances, officers and men from the stations that responded to his call for assistance.

The age of the motor fire engine had come – assistance was forthcoming, rapid, and allowed a far greater weight of fire attack to be undertaken. Never before had this happened on the Isle of Wight, or to Chief Officer Mursell who was suddenly faced with his contemporaries from East Wight all looking to him for his guidance and a combined plan of attack. Among the faces were Chief Officer’s Henry Frederick Jolliffe of Ryde, Wilfred Harry Brown of Sandown, Percy Robert Spencer of Ventnor, and Acting Chief Officer Harry Newton Bull of Shanklin. There was no procedural manual, no precedent had been set, and none of those present had the experience of it in an incredible 162-years of combined service.

Being a windless night, the fire wasn’t driven in any definable direction, but the heat output, fed by the many oils kept in the workshop, was great enough for it to spread in all. Chief Officer Mursell, blessed with five appliances and crews, made the logical and achievable suggestion – surround and drown. Entry had to be made from every direction to check any potential growth and spread.

Mursell’s men of Newport continued pushing inwards from St Thomas’s Square. To the west in St James’s Square, Chief Officer Jolliffe tasked his Ryde men with hauling multiple hoses in through the Wadhams frontage to seek a route to the workshop. They discovered that iron doors separated the workshop from the retail area, preventing fire spread in that direction. Easing open the warped ingress to attack the flames the heat was tremendous but working in stifling conditions at ground level allowed Ryde’s firemen to hit the seat of the fire. At the same time in the High Street having forced entry to International Stores, Ventnor’s men dragged charged hose in and up the stairwell, heading to the rear of the property from where they threw open the windows and began their work. On all sides ladders were pitched and firemen clambered across the roofs with charged hoses to direct more water down into the blaze.

Every vantage point was identified and used where feasible. The premises of one Arthur Wood was opened to allow hose to be dragged through to the rear yard. It was most likely the men of Sandown and/or Shanklin that utilised this access to haul hose through and mount the roof an iron store to direct water into the rapidly disintegrating building of origin – this checked the advance of flames on the south side – according to the County Press. The men from the Bay also made an entry into the south-east corner of the block, through the Wheatsheaf Hotel, hauling more hose with them.

Sandown Fire Brigade with Chief Officer Brown on the running board of their 1926 35hp Dennis turbine fire appliance.

A thank you placed in the County Press by Wadham & Sons. Why they chose not to include Sandown and Shanklin fire brigades is a mystery.

From Unity Hall progress had been made from the rear windows, encouraging the firemen to redeploy a firefighting branch to the passageway they’d withdrawn from earlier. Shortly after reengaging from this position a large tank of oil, unseen behind the rear wall of the store, suddenly exploded. Three Newport firemen were thrown off their feet as a vast sheet of flame swept overhead – after it had passed all three scuttled to safety with minor injuries.

The effect of the combined operation of the firemen was quickly apparent – stated the County Press – and by 11 p.m. only the smouldering mass of woodwork inside the bare walls remained and this was deluged with water.

The splendid manner in which the Newport firemen tackled an apparently hopeless task during the early stages of the outbreak brought forth expressions of admiration and appreciation from everyone. In view of the fierceness of the conflagration and the difficulties of reaching it they could hardly have had a more severe test, but they came through it with great credit.

Praise was lavished on the Borough brigade, its Chief Officer, and those that attended to assist, at the council meeting of eight days later. Alderman Steel remarked that a visitor from London mentioned that he had seen no finer display of coordinated firefighting in his many years observing the Metropolitan Fire Brigade.

When Chief Officer Wilfred Harry Brown penned Sandown Fire Brigade’s Annual Report for publication on 1 October 1928, he listed three incidents attended by his brigade in the previous twelve months, the Newport incident being uppermost – The first of these fires was one of the largest the Island has seen for some years and the fact that five Brigades were present shows what can be done now that most of the Island Brigades have adopted motor fire engines.

It proved a fitting swansong to Nicholas Mursell’s 34-year service in the Brigade. He retired a few months later in January 1928, amid surprisingly little pomp and ceremony. The IWFBF that Nicholas had worked so hard to resurrect after the First World War, retained his services as a committee member for some time after.

His son Leonard was also to resign from the brigade and relocate to Bournemouth. In February 1941 when Nicholas was 79, failing health compelled him to rescind the licence of The Castle Inn where he had been landlord for 56 years. He departed the Island to spend the remainder of his days with Leonard and family.

It was at his son’s home that he passed away the following year, 10 April 1942. Nicholas was laid to rest at Branksome Cemetery, Parkstone, Dorset.

A Lucky Find

On Saturday 5 April 2025, my wife and I were perusing shops in Yarmouth when I spotted two rank epaulettes in the display area. On closer inspection I thought I could see the Borough of Newport crest. Borrowing my wife's glasses confirmed what my blurred vision suggested and I couldn't believe I held Captain Mursell's items in my hands. The proprietor had purchased them at auction in Oxford around a year earlier without knowing anything of their IW connection. The items were very fairly priced and worth every penny I spent to bring them home.