Fire at the Theatre Royal, Ryde

19 May 1961

Still Image extracted from footage provided by image.films.net.

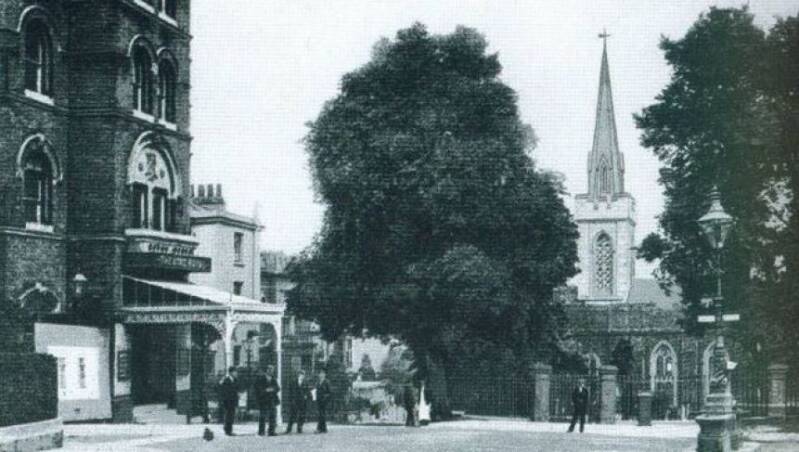

Since 1871 Ryde's Theatre Royal deservedly dominated the town's St Thomas' Square as an edifice of Victorian grandeur set in the main thoroughfare of the prospering seaside town.

Theatrics were embedded at the spot prior to construction of the Theatre Royal. From 1816 the site had been occupied by a market house erected by a joint stock company. In 1838 trading had reduced to such an extent to make the purpose of the building untenable. Considered an ugly functional construction, it was put to use as the towns theatre and proved to be a great attraction, motivating plans to pull it down in the late 1860's and replace it with the commanding structure that would become the Theatre Royal, opening in 1871.

Many years after its construction the IW County Press published an article describing it a little on the small side for a theatre, with a capacity for 1,000 patrons, yet with its pit, dress circle, upper circle and gallery, its row of ornate boxes and heavenly embellished ceiling, it was considered unique and regarded with warm affection by those who visited it.

Many stars of the era graced its boards, it even hosted a young Winston Churchill at a time when he was pleading the Liberal cause to potential voters. Decades of entertaining royalty, dignitaries, and the hoi polloi followed until the arrival of motion pictures compelled a rethink. Theatre management invested in the technology and alterations required to project movies. By the 1920's, other than occasional productions by Ryde's Amateur Operatic and Dramatic Society, the theatre was increasingly occupied by enthusiasts of the silver screen.

Over the course of the following decades, under the ownership of IW Theatres Limited, to oblige the needs of cinemagoers, down came the boxes and nostalgic trappings of the age of stage drama and the capacity was reduced to 600 seats, with the structure described in succinct technical terms by the Island's Chief Fire Officer Richard Sullivan.

Brick walls, all floors timber, traditional close-boarded timber, ridged slated roof with several dormer windows. The main auditorium curved ceiling match-boarded on timber joists, under drawn with fibre board and overlaid in roof space by 7/8" timber floorboards for 75% of area. The ceiling over stage area from proscenium arch to rear wall renewed in recent years with Asbestolux on timber joists. The ceilings in offices in front of building, lath and plaster.

On the evening of Friday 19 May 1961 the theatre paid host to a throng of Tony Hancock fans watching their comic hero progress through a chaotic romp concerning a disillusioned London clerk turned failed Parisian art fraudster in a way that only Hancock, with his deadpan expression and countenance, could deliver to such mirth.

At 22:22 the movie ended.

Patrons dribbled out of the building into a pleasantly mild Ryde evening disturbed only by an embracing south-westerly breeze. Some nipped to the Colonnades for a late pint at The Turks Head where a Whitsun extension was in place, others headed home chatting and giggling over Hancock's calamities.

The Commissionaire bade farewell to all at the exit, cleared the building and closed the doors. As was customary he isolated all lighting circuits excepting the Police light in the foyer, signed off the premises fire book with All satisfactory and left with the relief manager, locking the doors behind them. The pair lit cigarettes and chatted for ten minutes beneath the glazed awning before departing on their separate journeys home.

22:50 - a passer-by walking along Lind Street close to the rear of the theatre heard glass shattering. Looking up to the high window set above the stage of the theatre's back wall, he saw smoke followed by a whoosh and a tongue of flame that leapt skyward in harmony with a muffled explosion from within.

The first concern of that person was not the theatre, but the cars parked beneath the window in Lind Hill. He accessed each and moved them to safety. Such had been the reverberation caused by the explosion, that it attracted the attention of Jack Pugh, licensee of The Turks Head when it shocked his patrons revelry to silence. Equally stunned was Mr A.D. Wesson of St Thomas' Street. Both men peered from their respective windows, both dashed for their phones and spun the dials to call 999 with Wesson later stating 'I've seen some fires in my time but never one which went up like this!'

23:02 the Duty Officer at Ryde Police Station received notification of a fire at the Theatre Royal and activated the Fire Brigade call-out system.

Across the town, bells mounted to the walls of firemen's houses shocked occupants into wakefulness, including many of the men who had experienced firefighting in both war and peace. Collis, Williams, Cogger, Ballard, Perkis, surnames embedded in Ryde firefighting folklore dashed from front doors into the night alongside younger men yet to make their mark in the brigade, including Dave Corney and Reg Burgess, the latter of whom had once been a projectionist at the theatre. Both men had joined in the previous year, and as they sped towards the station that night they had no idea that this occasion was to be their first big one!

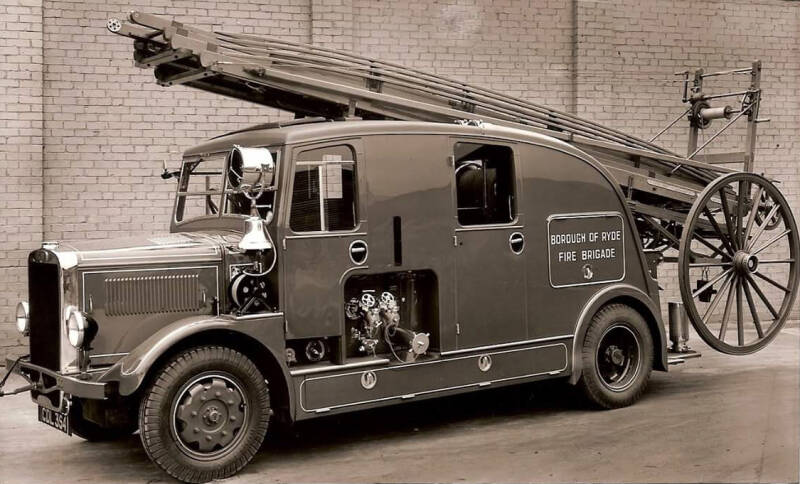

The first to arrive at the station piled aboard Ryde's 1939 registered 'Ethel', a mighty Leyland FK Pump Escape which had served the town throughout the war and continuously since then as the districts primary engine known simply as Station 4 Pump Escape, 4PE. For Corney and Burgess this was to be their first major conflagration, for Ethel it was to be her last.

Station Officer Len Williams had been firefighting in Ryde since the days of the pre-war Borough Brigade in 1935. He'd served through the war during which he experienced the worst that the Luftwaffe had inflicted on the Island.

After the war, when the National Fire Service was disbanded, Len (right) remained in service at Ryde and was a popular choice for promotion to Station Officer in the summer of 1958.

Len's rapid northbound journey along Swanmore Road from his home at Osborne Road, was headlined by a fierce throbbing orange glow in the sky to his front. His years of experience forewent any reluctance to doubt his instinct, his first action on arriving at the Fire Station was to order Fireman Long, watchroom orderly, to contact Brigade Headquarters to 'make pumps four, turntable ladder required'.

Brigade HQ recorded receipt of the make-up call at 23:03.

While BHQ were putting the wheels in place to obtain the resources Station Officer Williams requested from Sandown, Bembridge and Newport, he clambered into his boots and leggings, buttoned his blue tunic, and took his place in Ethel's front passenger seat. As the crew cab filled, the driver thundered Ethel out of the bi-fold doors, expertly guided the heavy machine into the High Street, and slewed to a halt at the front of the theatre amid a swarm of gasping onlookers at 23:06, being closely followed by Ryde's second appliance, commanded by Leading Fireman Collis.

23:08 - BHQ contacted Chief Fire Officer Richard Sullivan at his home address, alerting him to the fire and the scale of the operation being put into effect.

Like Station Officer Williams, CFO Sullivan was a veteran of war firefighting, having served as NFS Divisional Officer at Bournemouth before a transfer to Column Officer on the Island from 1946 until disbandment of the nationalised service. However, despite being colloquially known as the father of the IW fire brigade, he hadn't been the County Council's first choice for the job. Arthur Edward Bowles, fresh from wartime service including selection as Divisional Officer of No.5 Column of the NFS Overseas Contingent, had been the preferential candidate after interviews held in the late summer of 1947. However Bowles, in post on the Island by autumn 1947 as chief-elect of a brigade-in-waiting for NFS disbandment, argued vociferously against what he saw as a weakness in the Council's planned investment and proposed strength of the brigade. Finally, frustrated that his employers refused to acquiesce to his reason, Bowles quit the post on New Years Eve 1947. With just three months before launch of IW County Fire Brigade, the Council had no time to dwell. Sullivan was already on the Island and familiar with the terrain as senior officer of the NFS in swansong. He had been a strong applicant for the Island's CFO role, placed second behind Bowles following the interviews. The Council made the only logical move available to them and re-engaged in talks with Sullivan to secure his services. Winning himself concessions from a position of strength, the news broke on 24 January that he had accepted terms and would be the IW Fire Brigades first CFO, a role he maintained until retirement in June 1965. Bowles went on to serve in senior roles with several brigades including a stint as Commandant of the Fire Service College.

As CFO Sullivan prepared to leave his home and attend the fireground, he received an update by telephone from BHQ advising him that Station Officer Williams had upgraded the incident further - make pumps ten!

Station Officer Williams' initial size-up of the situation identified that the theatre was effectively lost. The roof was alight from end to end, soon followed by a large portion of it crashing down, flailing in shattered parts through the orange glow before crashing into the auditorium below, sending a vast cloud of dust and embers to billow from the openings and upwards into the night sky. The searing heat radiating from the building served only to assist Police in their attempts to keep the crowds at a safe distance. In accepting that the building was lost, Williams identified his primary concerns - radiated heat causing fire in other buildings located in close proximity, most notably The Crown Hotel, and the reality that with every piece of structural timber that succumbed to the fire, the integrity of the lofty external walls of the theatre were weakened and represented a substantial danger of partial or total collapse.

Among those standing agape at the havoc wreaked on the once proud structure was a 14-year-old boy who recalled 'I remember being woken up by all the noise and then walking to the fire and watching the flames as they bolted into the night sky. It was a very memorable night.

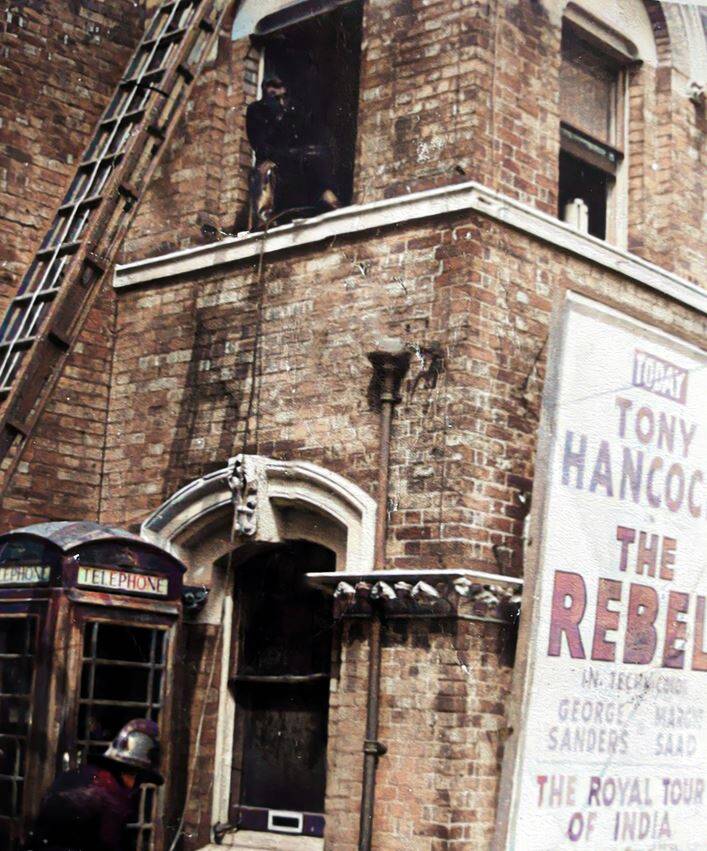

The boy may have seen images such as the scene on the left, a still image taken from footage captured during the event by persons unknown.

CFO Sullivan drove with urgency to Ryde and took command of the incident at 23:18.

By then Williams' plan to protect adjacent properties with cooling jets, combined with directing firefighting jets into the burning mass within, was well under way. Sullivan backed Williams plan as firemen worked in rotation to clamber up ladders positioned against the fragile walls, take a leg lock, and direct water jets through the glassless windows into an mesmeric apparition of volcanic properties.

Every available length of layflat hose was deployed around the fireground, attacking the fire, defending other buildings on all sides with eight main jets supplied by five pumps. Instantaneous couplings, that marvellously simple British design, were snapped into place on hydrants set in the older mains, but the majority were fed from the recently installed 8" main, allowing for a copious supply that passed through the multitude of hoses that writhed like monstrous pythons at fluctuations of pressure. Rivers of bubbling heated water ran from the foot of the structure, thick with debris and soot laden as black as tar, gathering to form a torrent of detritus that gushed down St Thomas' Street, passing the home of 82-year-old Maude Murray who watched in a melancholic stupor.

It had been 67-years since she had first stepped onto the boards of the Theatre Royal. Since then a forty year career in showbusiness had taken her across the world to France, Italy, Canada and the USA, including a role in the Edison Studios 1914 American movie 'Lost A Pair of Shoes', before she returned home to retire, within a stone's throw of the theatre where it all began and where her heart truly lay. As she watched fire destroying the centre of her youthful dreams she sobbed uncontrollably.

Above - Ordnance Survey 1:25,000 map of Ryde. This edition was published in late 1961 but still shows the theatre in place at the centre of this extract. The 'TH' indicates the Town Hall and is not an abbreviation for 'theatre'.

So terrific was the heat that despite the weighty application of cooling jets, windows of the fruiterers in the Colonnades cracked and the frames blistered. The Crown Hotel, imminently threatened by both fire and the potential for collapse, remained the focus of the CFO's continuing plan. Among those deployed for this objective was Harry Cogger, fireman of 18 Pellhurst Road, who ascended a ladder pitched to the south elevation in the narrow entrance to the garage located between the theatre and the hotel. In the darkness, clutching a hose and branch, he took a leg-lock just shy of the head of the ladder and directed his jet of water through the glassless window. Ten minutes after midnight, with little vision but for the blinding glow of the fire within, Harry had no awareness of the precarious situation overhead until suddenly, without warning, a loosened length of iron guttering tore from its weakened fixings and came clattering down upon him. Incredibly he maintained both his hand grip of the branch and his leg-lock of the ladder, but required assistance to be brought to the ground with what appeared to be a serious leg injury. He was despatched to the County Hospital with all haste. More incredible still is that after receiving a check for broken bones and a dressing for the wound, he was returned to the fireground, reported to the CFO, and carried on with his duties.

During Harry's brief spell at the hospital, the CFO was confident enough to submit a fire surrounded message to BHQ. Forty minutes later this was followed by the Stop message. In 1961 stop messages were still being used as intended when created by London's Superintendent James Braidwood one-hundred years earlier (see here) - indicating that no further resources were required to deal with the fire - rather than modern usage which tends to see the Stop used to indicate that the incident is closing. In the era concerned, firefighting operations would likely continue for many hours after submission of the Stop and indeed when CFO Sullivan did so, the fire at the Theatre Royal was far from over.

By that stage the original crews from Ryde (Station Officer Len Williams), Newport (Station Officer Harry Bradshaw), Sandown (Leading Fireman Charlie Woodford) and Bembridge (Station Officer Bill Barnett, pictured left during war service with the NFS) had been joined by further pumps from Newport and East Cowes, all of whom laboured in difficult and threatening conditions as a stiffening breeze spread airborne embers as far afield as the pier.

02:21 - CFO Sullivan was satisfied that the worst of the incident was behind them, radiated heat had reduced substantially and the fire threat to neighbouring properties with it. Sandown's crew were the first to be released from the fireground, and after a difficult scrabble to extricate sufficient lengths of hose from the interwoven mass to restock their appliance, they made their way back to Grafton Street.

As Ryde's firemen had been first on the scene and had taken much of the early heat punishment, the CFO stood them down to return to their homes. Station Officer Williams was the last to leave the station, signing off the watch log at 03:35. By a poor redistribution of relief resources, two hours later the Ryde men were turned out again and at 05:45 Station Officer Williams and his weary men remounted Ethel and returned to the scene thirty minutes after the first glimpse of sunlight on the horizon.

Above - the scene at the front of the stricken theatre on the morning of 20 May. 'Ethel' is positioned to the left.

As all firefighters have experienced, fatigue plays no part when the flames are high and adrenalin powers individual actions in response to the developing emergency. But as soon as the first rays of sun break the gloom, subtly reminding all that they substituted the safety and cosiness of their beds for a night of physical exertion, heat, cold, and damp, the weariness creeps into the mind. It is then, statistically, that firefighters are most prone to injury through accident. This is the time when a friendly member of the public armed with a tray of teas is most popular.

The correspondent of the County Press who arrived to observe the scene at first daylight described it thus - On Saturday morning the interior of the cinema was a smoking mass of rubble and blackened, twisted girders. Poised high up above the entrance - the last and least affected part of the building - could be seen the ruined film projectors, still pointing down to where the screen had once stood. At the front posters still advertised 'The Rebel' starring Tony Hancock, and on the Lind Street wall was a poster announcing a forthcoming film at the Scala entitled 'Too Hot to Handle'.

Firemen were busy salvaging the few pitiable objects not consumed by the flames. The numerous offices in the four-storey front of the building were used as an administrative centre for IW Theatres, and scorched chairs and tables were removed from an upstairs window. Barriers were erected and patrolled by Police and crowds of sightseers gathered.

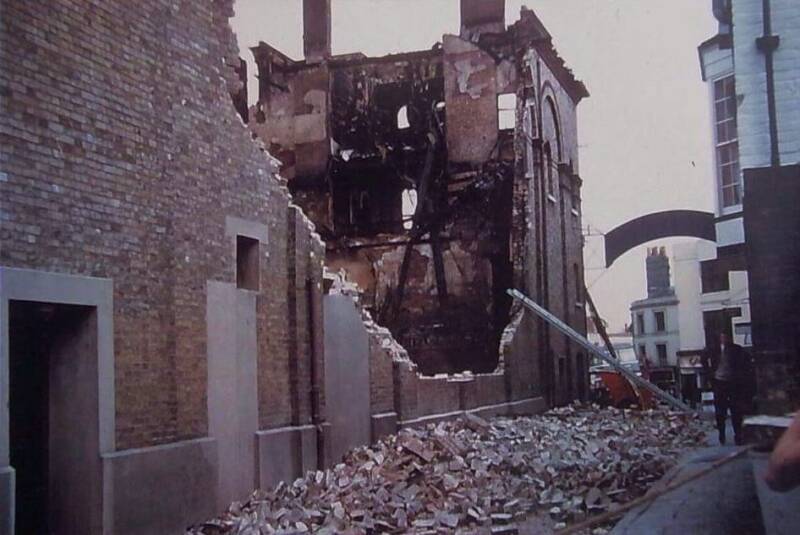

Above - the debris strewn Crown Street between the Theatre Royal and The Crown Hotel.

Fireman Arthur Cogger perched in a window space at the front of the theatre during the salvage phase.

By 14:00 that afternoon the remains of the building had been formally condemned and demolition was urgent, considering the danger the remains represented. Borough Surveyor Mr W. Rowbotham arranged for Shorwell Plant Hire to conduct the task, assisted by men of Ryde and Newport fire stations.

A turntable ladder was pitched to the rear and a lone fireman was projected skywards to connect a steel hawser to the structure close to where the first eyewitness had seen flames shooting just before eleven o'clock the previous night.

With the other end secured to a tractor, a modest tug of the hawser resulted in many tons of brick crashing into Lind Hill throwing up a dense cloud of dust. Next the north-west corner came down as the Lind Street side was seen to sway perilously as constables ushered back sightseers tempted to stray too close for their own safety.

Above - the view from the Town Hall the morning after the fire. Lind Street is below with The Turks Head public house to the left.

Above - an image captured from Lind Hill showing one of the firemen attaching a steel hawser to the remains of the west elevation.

After making up their soiled gear and assisting with demolition to ensure the safety of the area and to allow Lind Street to reopen, Ryde's firemen returned to the station and were dismissed at 21:55 that Saturday night after a tiring days work. Ryde's grandest place of public entertainment for ninety-years had disgorged its last patrons and crashed into debris and dust in a little under twenty-four hours.

On the Sunday the tricky task of removing the salvageable projectors was taken, before the remaining elements of structure were toppled to the ground. With the site a mass of steaming debris, CFO Sullivan concluded his fire report - From eyewitness's accounts of the fire in the early stages, it does appear that the fire started from behind the screen or screen area and while every investigation has been made as the actual cause, the total destruction of the building and contents prevents any cause being established.

For the town of Ryde, the loss of such stunning architecture of historical importance was emphasised by the subsequent installation of the soulless carbuncle that for many years accommodated the National Westminster Bank until they vacated the site with the closing of the branch in 2023. Since then Ryde Town Council have expressed an interest in acquiring the building.

The details above are drawn from original documents including CFO Sullivan's report to the Isle of Wight County Council Fire Brigade Committee, various station watch logs, first-hand eyewitness accounts and editorial from the IW County Press.

If you have enjoyed this page, why not make a small donation to the Firefighters Charity.