Built to last!

The Shand Mason engine of 1873

In 1850 William Joshua Tilley, 66-year-old proprietor of Tilley and Co., retired from the business he had established where he had been designing and manufacturing fire engines since 1828.

Passion for firefighting appliances ran rich through Tilley's veins, but it was not his own three sons to who he turned to maintain the family business after his retirement. Of his five daughters two were married to like-minded men of engineering and business acumen - James Shand and Samuel Mason.

Unlike Londoner Tilley, James Shand was a 22-year-old Scotsman when Tilley appointed him as business manager in 1845. Born in Edinburgh in the year prior to James Braidwood's creation of the world's first municipal fire brigade in the city, he would no doubt have grown up seeing something of, and perhaps being inspired by, the vision of the expertly trained and organised firemen thundering through the city on horse-drawn manual fire engines. As a young man Shand acquired a varied knowledge at the dawn of developing mechanical engineering as a pupil of James Slight, engineer to the Highland and Agricultural Society of Scotland.

Shand would have been ten years old when Braidwood was lured to relocate to London and repeat what he had achieved in Edinburgh by creation of the London Fire Engine Establishment. Given Tilley's prominent place in the history of fire engine manufacturing and Braidwood's intimate involvement with technical developments throughout the period, there is every chance that the two Edinburgh men met in their professional capacities.

When Shand took the reins at Tilley's, he recruited his brother-in-law Samuel Mason of Newington to join the firm and together they established Shand Mason and Co., south of the River Thames at 75 Upper Ground Street, Blackfriars.

In 1829 John Braithwaite, a London based pioneer of steam locomotives, designed and manufactured the Novelty (left) one of the first, possibly even the very first, steam-powered fire engine. Soon after his arrival in London, Braidwood was keen to trial the new technology, but his firemen were resistant and the engine received little operational use before it was destroyed by an angry mob, including some of the firemen.

Twelve years later, without any apparent connection New York firefighters were equally unimpressed with their first steam-powered fire engine. Whilst it wasn't destroyed in frustration, it became a dust-laden relic.

But the nucleus of an idea was germinating.

Shand and Mason remained committed to improving the manual fire engine, but in 1852, at the behest of Braidwood, they designed and fitted a steam powered water pump to a London Fire Engine Establishment fireboat. Braidwood's intention was clear, his Thames based fire floats were a cumbersome design requiring deck space for 120 men to teeter in the swell while swinging the handles of a vast manual pump. The experiment was so successful that Shand put his design brain into overdrive and created a steam fire float not only capable of delivering jets of water far beyond the range achievable by 120 men, but could also propel the craft itself. For the progressive James Braidwood this offered a major advancement and naturally progressed to James Shand designing a land-based wheeled steam fire engine which met the approval of both Braidwood and his firemen.

The introduction of steam power was as epiphanic in firefighting as it was in all other areas of development during the industrial revolution. Despite the instant success of the land steam fire engine, the marketplace for the comparably expensive engines was modest, and Shand Mason and Co., didn't lose sight of the staple market of supplying manual fire engines to the hundreds of provincial brigades with frugal purses. Production and sales of the steam engines was ground-breaking and lucrative, but demand for cost effective basic appliances remained the backbone of the business.

France, like Britain, was enjoying a heyday of design and technology, and had staged national exhibitions for many years, culminating in the French Industry Exposition of 1844 in Paris. The rapidly changing world of industry and commerce encouraged others to follow suit, and in 1851 the Crystal Palace hosted the globe's first international event of its kind, largely driven by Prince Albert and held under the title of the Great Exhibition of Works of Industry of All Nations. Shand Mason and Co., took their place at the five and a half month event, and here learned the benefit and knack of selling to a browsing audience from many nations.

This was followed by the 1855 Exposition Universelle in Paris, 1862 International Exhibition in London, a return to Paris in 1867 before Austria announced its intention to host Weltausstellung 1873 Wien (Austrian International Exhibition) of 1873, more commonly referred to as Vienna's World Fair.

James Shand and Samuel Mason were keen to explore this new opening.

The Vienna Fair, which opened on 1 May and closed on 31 October, was a vast arrangement. So vast was it that the Reports on the Vienna Universal Exposition published by Her Majesty's Stationery Office, listing exhibits just from Great Britain and eleven of her colonies, amounted to over 800 pages of text.

On Page 27, under List of Firms who Lent Objects for Use, is listed a reference to Shand Mason and Co. - Patent equilibrium steam fire engine, capable of delivering 1,000 gallons per minute, throwing to a height of 200 feet through a jet of 1 7/8 inch diameter, fitted with patent inclined water tube boiler by which steam is raised to a pressure of 100lbs. to the square inch, in 6 1/2 to 7 minutes from the time of lighting the fire...

So continued the 31-line glowing reference to Shand Mason's most up to date cutting edge steam appliance, before closing the section with what appears in comparison to be little more than an afterthought...

A manual fire engine of the same construction as those in use by London Metropolitan Fire Brigade, and also by municipal and volunteer fire brigades in Great Britain, and all parts of the world.

What this perfunctory reflection fails to account for is the inordinate amount of time and effort James Shand and Samuel Mason invested to ensure their most basic of fire engine models was not only eye-catching but met with the approval of Austrian-Hungarian high society.

The brightly painted red flanks of the engine and frontal portions of the water case were adorned with brilliantly stencilled illuminated copies of the Austria-Hungary coat of arms.

The display received approval and may have led to orders, but the elaborately decorated appliance itself was returned to Blackfriars in early November.

Seven months later, at 13:30 in the afternoon of Sunday 5 July 1874, the Reverend W.F. Fisher discovered fire affecting the thatched roof of his home at Fernhill Lodge, Wootton.

In the following week a correspondent of the Isle of Wight Observer wrote - The roof was soon in a blaze from end to end, and most of the contents of the upper rooms were destroyed, whilst the furniture of the lower rooms was being rapidly removed by the neighbours. When Superintendent J. Reynolds, of the fire brigade came on the scene with the new fire engine, he found the place in ruins.

James Reynolds was the 49-year-old superintendent of Newport Fire Brigade - the new engine being the very one displayed at Vienna in the previous year. How much Newport paid for it and how and when it was transported to the Island isn't known, but it arrived bearing the Austrian-Hungarian coat of arms, was repainted to bear the words Borough of Newport on either side and was to bear witness to many of the Island's major conflagrations until the 1920's when it was replaced by a motor fire engine.

Notwithstanding the futility of the Shand Mason's first run out to Wootton, its pumping handles were swung in anger for the first time ten days before Christmas 1874 when fire ripped through the railway station of the Newport - Cowes line. Alas the fire was too developed for the efforts of Newport's firemen to make a difference and the wooden structure was left a mass of smouldering ash and embers.

It was a less than distinguished first two outings for the engine, but Reynolds, with 16-years of firefighting experience behind him, was determined to ensure his men were proficient and skilled in its use. His training methods had no quarter and often sweat laden firemen were seen manually heaving the weighty appliance through the streets of the Borough with Reynolds chasing behind throwing curses and encouragement in preparation for those occasions when a fire call was received and no horses to pull the engine could be found. No one could argue his practices when on one occasion a fire report was received from Parkhurst, no horses were available, and the men were required to manually haul the engine up Hunnyhill and immediately get to work on arrival at the scene.

Reynolds retired from the service in 1880 and proudly handed over his well maintained engine and disciplined men to his successor Charles Osborne.

Osborne was a 32-year-old local man with a pedigree in engineering, the perfect commander to lead the brigade in the late-Victorian era. Within months of his arrival Osborne's association with the Society for Preservation of Life from Fire ensured the brigade were supplied with a wheeled escape ladder, described in the IW Observer as a terrible looking implement - one which in harmony with the Shand Mason was to save much life and property over the next four decades.

Under Osborne's command the brigade maintained the standards set by Reynolds. In 1884, ten years before the founding of the IWFBF and the first island wide drill competitions, an ad-hoc competition was staged at Steephill Castle. Newport's firemen drilling with the Shand Mason, came away with four of the winners trophies up for grabs that day. It was as well that the men of the Borough and their equipment was of such quality, as the decade that followed was littered with a staggering number of serious fires in and around the district. The engine never failed to operate efficiently, and caused distress only to Fireman Fuller who, in a moment of poorly judged horseplay, toppled from the engine during the Illuminated Cycling Procession of October 1891, and fell beneath the wheels, surviving but not without considerable injury.

On the 28 May 1892 the Shand Mason's handles were furiously pumped for the most protracted of periods during a fire, so devastating and controversial that letters and comments regarding the events of that night swamped the pages of the IW County Press when the matter resurfaced over thirty years later.

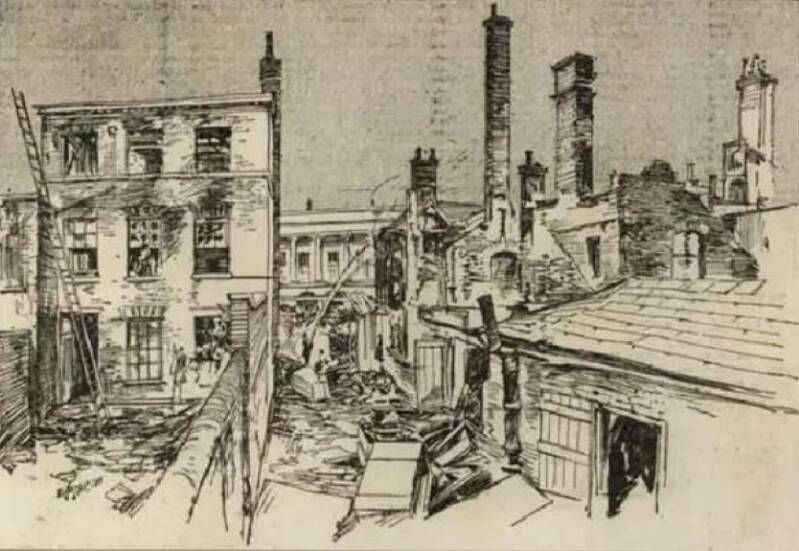

The fire that ripped through the ground floor of a High Street store belonging to Mr Wall (across the road from the Guildhall) was far beyond the capacity of the Borough brigade and its single Shand Mason engine, despite the furious sustained efforts of the volunteers who worked in teams to keep the handles lowering and rising in harmony. Soldiers of the Kings Royal Rifles, alerted by a sentry spotting the bright orange glow in the night sky, arrived from Parkhurst with the garrison equipment and committed as feverishly to the task as the firemen. By dawn the next morning the fire had carved such a swathe from the terraced structures that a sketcher submitted work to the Illustrated London News showing a side view of the Guildhall previously impossible from behind Wall's premises (below).

In the aftermath Newport's firemen fared poorly in the view of the public with several submissions to local newspapers calling into question the efficiency and fitness of men described as too corpulent to be of use, being unfavourably compared to the men of the KRR who won praise for their efforts under the command of a Pioneer Sergeant.

One wonders if, in part, it motivated the outcomes of the firemen's pay review conducted by the Borough authorities four months later. Charles Osborne, the committed and honourable captain, was granted a rise of an incomparable percentage to his men.

Jacob Peach was a diligent townsman and businessman, popular on many fronts and for none more so than his skill as engineer in charge of the operation of the Shand Mason engine.

He, in cahoots with firemen Obediah Jackman and John H. Stubbs, backed by their firefighting colleagues, but without reference to Captain Osborne, submitted a formal letter of protest to the Mayor and Corporation. Citing the firemen's raise of just five shillings in comparison to Osborne's £3 3s increase, the dissenting trio played a bold, and they considered a trump card - asking for an additional five shillings and sixpence for all firemen or their mass resignation would be effective on 23 February 1893.

The reaction in Newport's chambers of power was anything but acquiescent.

While the protesting firemen enjoyed a quiet Christmas in expectation of a New Year pay increase, the Corporation wheels went into overdrive to recruit and train a brigade of volunteer firemen to replace them. Public opinion was managed by a clever spin campaign with the connivance of the County Press who published the Corporation's statement on the 4 February that the firemen cannot be congratulated on the attitude they have assumed and their resignations are to be accepted.

As the volunteers continued their training under the tutelage of a former Metropolitan Fire Brigade officer, the Corporation chose to follow the policy operated successfully at Sandown Fire Brigade for many years, and allow the men to vote for their choice of captain, deputy and engineer. What the Corporation hadn't considered was the position of Captain Charles Osborne, who, through no fault on his part, was left out in the cold when the volunteers voted Percy Shepard to be their leader. Out of a belated sense of shame the Corporation advised Osborne that his services would not be required after 23 February and, several months later, offered him a substantial pay-off, which, to maintain his integrity, he told them where they could stick it.

The most awkward of situations developed on that evening of 23 February. The outgoing paid firemen of the brigade had been instructed to attend the station at the Guildhall, to surrender their equipment and effects to the volunteers. One can only imagine the atmosphere. As fate would have it, while these thorny transactions were being undertaken, a call was received regarding a fire in a Pyle Street property. A struggle ensued over the Shand Mason between the paid and volunteer firemen. When the still arguing mass arrived dishevelled at the scene of the fire, wrestling began over lengths of hose and branches. Both Captain's Charles Osborne and Percy Shepard, the former with over thirty years of firefighting experience and the latter on his first shout, were in attendance, and agreed the needs of the call were to be placed above all other matters. Settling on a compromised form of command, in which Shepard was probably a tad relieved to have the chance to study Osborne in action, the effect calmed the waters between the firemen who got on with the job in hand - only for it to flare up again after the flames died when the outgoing men began to bustle equipment from the volunteers, packed the hose cart, returned it to the station and tossed the remains of their soiled gear on the floor and departed for the last time.

The Shand Mason, battered by years of operational use and that evenings battle of possession, was returned by the volunteers, blooded by their first action.

Above - the Shand Mason, photographed in use during one of the IWFBF drill competitions hosted by Newport.

On 4 April the volunteers reported that the engine had been entirely overhauled and repainted to reflect the status of the new Newport Volunteer Fire Brigade. As not one of them had any firefighting experience other than the chaotic events in Pyle Street in February, they struggled to become experts. That changed before the end of the year when the brigade was joined by former Brighton fireman and expert engineer Ernest Hayles. Hayles moved to the Island and established a business in Newport with his wife and was initially appointed as Voluntary Second Engineer. Ernest was soon to become a local living legend in an era where the deeds of individual firemen were lavishly described in the pages of the local press. His committed, and at time reckless, endeavours in the uniform of the NVFB were to earn him much admiration from the public and scorn from some other firemen - twice he fell from the roofs of stricken properties during fires, adding to his reputation in both contexts.

Hayles cared for the Shand Mason far better than he cared for himself, the machine being remarked upon at shows and competitions for its excellence in appearance and operation. So admired was Hayles' work that the Corporation retained his services as caretaker of the station and equipment for £25 per year (at a time when his counterpart at Sandown was earning a fifth of that sum).

Hayles' judiciously greased Shand Mason axles thundered through Cowes in the spring of 1894 and ended with the driver, Kemp Mearman, being hauled before the County Petty Sessions on a charge of furious driving! The event almost certainly represents the first occasion when an Isle of Wight emergency worker was called to account for his actions on the highway. The matter was exacerbated by the fact that there was no fire. Mearman conjectured that the startling speed at which the engine, with a crew all-up gripping frantically to anything and everything to remain onboard, conducted the rip-roaring course from Newport to Cowes, through the town's principal streets and back to the Guildhall, was an essential training exercise. So aggressive was their pace through the seaside town that one woman fainted, others screamed in alarm and carts of produce were upset by startled barrow boys.

The Shand Mason remained the backbone of Newport's volunteer brigade until the Corporation decided that volunteer firemen were becoming uncontrollable, and elected to return to a system of part-time paid men in November 1908. By then the engine had outlived its caretaker, Ernest Hayles, who died suddenly in 1906. The fact that his family posted a notification in the classifieds requesting that none from the brigade were to attend the funeral adds mystery to his demise.

Conversion from voluntary to paid status was no less controversial than the debacle of the reverse decision fifteen years earlier. Several of the men who had freely given their time to the brigade for many years, found there was no position for them in the ranks of the paid brigade. The Corporation planned that the change in constitution of the Borough Brigade was to take place at midday on Tuesday 24 November 1908 - all outgoing volunteers were instructed to attend the Guildhall and submit their uniforms and equipment at that time. In an attempt to avoid a repeat of the Battle of Pyle Street of fifteen years earlier, the Corporation instructed the members of the paid brigade to not attend and reorganise the station, uniforms and equipment until the evening.

It was a wise decision as fate attempted to meddle once more. While the volunteers were in the fire station at midday a call was received to a fire at the rear of the Barley Mow public house in Shide. The volunteers willingly responded, in isolation, under the command of Captain Nicholas Henry Thomas Mursell who was to bridge the period and evolve from volunteer to paid officer. Mursell's attachment to the brigade had been extensive, having begun as a boy knocker-up in the 1870's. By the time of his captaincy he was the well known landlord of The Castle Inn.

The volunteers dealt with the Barley Mow incident, returned to station, and those for who there was no role in the paid brigade deposited their gear and departed. In the evening the paid men assembled at the station and were in the process of sorting the pile of uniforms when a call was received for a fire in a carpenters shop to the rear of Chapel Street. Captain Mursell and his men were on the scene rapidly and suppressed the flames with thrifty work, for which they were paid, the cost being recouped by the Corporation from the Phoenix Fire Insurance Office.

By the end of 1908, Sandown, Shanklin and Ryde brigades were each sporting the latest steam powered fire engines. Even when it took Shanklin's steamer to arrive and deal with a fire that the Shand Mason could not, at the Nodehill store operated as Jordan and Stanley's, Newport Corporation refused to budge on the issue of upgrading the brigades appliances on similar lines. Incredibly Newport entirely skipped the steam age and were still operating their, by then, fifty year old manual engine, while Ventnor were enjoying the throaty growl of a Leyland FE Braidwood motor fire engine in 1923 - the first such engine on the Island.

Eventually the Borough's authorities had to sit up and take notice, but despite borrowing and trialling a matching Leyland appliance, the Corporation opted to purchase a comparatively feeble Ford Stanley appliance, much to the dissatisfaction of the firemen for whom the appliance became a subject of much mirth when gathering with other brigades at IWFBF events.

Despite the diminutive stature of the Ford Stanley, its arrival heralded the end of the operational life of the Shand Mason - but not for long.

Throughout the development of brigades in central and east Wight, the west had remained entirely unprotected from fire. When change came it wasn't induced by the Rural District or Parish councils, it was an inspired decision by the short trouser-clad young men of the Freshwater Rover Scouts under the command of Scoutmaster Wilfred Jeffrey, who formed the districts first fire brigade.

The Freshwater Rover Scouts Fire Brigade were an instant success and achieved wonders more rapidly than an ad-hoc scheme could be expected to - a remarkable credit to the scouting organisation of which they were a part.

The Rover Scouts first serious conflagration involved Freshwater's Palace Theatre in May 1929. Newport, confident of making meaningful response times to the West Wight in their Ford Stanley, responded to the call. So impressed was Captain Percy Shields with the progress the Scouts had made to suppress and contain the fire, that he wrote of it in the local press, and from thereon endeavoured to assist the Scouts with acquisition of equipment - including the gift of the Shand Mason manual fire engine. Housed in the Black Hut at Freshwater, the engine was once again treated as an esteemed machine in the hands of the firefighting scouts and was to see almost another decade of operational use before the Freshwater and Totland parish authorities were awoken to their responsibilities by the impositions of the Fire Brigades Act 1938. Formation of the Freshwater and Totland Joint Fire Brigade followed, equipped with an impressive motor appliance. Many of the former boys of the Rover Scouts brigade were now men of the Joint FB, and the Shand Mason was finally, after 65 years of service, decommissioned.

Mayor of Newport, Mr A.E. King (left), commonly known as Mr Ting due to a speech impediment that prevented him from correctly pronouncing his own name, discovered the Shand Mason abandoned and neglected at an Island scrapyard.

The Mayor took possession of the engine and had it restored to its original condition before being transported to Newport Fire Station on the day that the Isle of Wight County Fire Brigade was formed, 2 April 1948.

Speaking at the ceremony at which the National Fire Service formally handed over its assets, personnel and functions to the County Brigade, King described how he was saddened that the Government had chosen to enforce the creation of county services and that there would be no return to the pre-war Borough Fire Brigade in which he had taken a great interest.

He then introduced the Shand Mason engine, with a potted history, and explained that he intended to loan it to the County Brigade for the purpose of exhibition at historical or humorous occasions. From there on the engine was kept at Newport Fire Station and did indeed appear in carnivals, processions and shows as he had decreed.

The image on the left shows the Shand Mason, looking perhaps less than glorious, in mock Hillbilly appearance poised in Town Lane in preparation to join a carnival procession in the 1950's.

On 15 September 1955, Mr King, then serving as Chairman of the County Fire Brigade Committee, was invited to Newport Fire Station to present Long Service and Good Conduct medals to a range of firemen from across the Island.

During the ceremony Mr King announced that his loan of the Shand Mason to the brigade was to end, and they were to keep it in perpetuity.

He had also arranged for nine veterans of the old brigade, attired in as much original uniform and brass helmets as they could muster, to attend and put on a display of old-time firefighting the manual way with the Shand Mason for the delight of those attending. Under the command of Newport's former Chief Officer Sydney Scott, by then aged 73, the ageing firemen displayed a range of drills rarely seen since the days of the pre-First World War IWFBF competitions.

The Shand Mason continued to appear for many years at public events on the Island, noted for its displays on St Helens Green in August 1968, and throughout the late 1960's on Sandown Esplanade as a feature of fundraising events for the Fire Services National Benevolent Fund (on the right, at Sandown Town Hall, 1967).

In May 1971 the County Press carried an advertisement that the Shand Mason had been loaned by the Brigade to Norman Ball, of Bullen Road, Ryde, as one of 21 vehicles at an exhibition of transport held at the IW Indoor Bowling Club.

The engine appeared alongside a First World War staff car used by George V, cars used in The Avengers and others that Ball and his family had acquired over a four year period touring the country for suitable exhibits.

The related press article described how Ball expressed the desire to establish an IW Transport Museum on the site of the former Ryde Airport.

In May 1973 Ball brought the engine for exhibition at the Ancient and Modern Machinery Rally held at the County Ground, where it was displayed alongside and somewhat dwarfed by the County Brigades recently acquired hydraulic lift platform.

After 1973 the whereabouts of the engine remains elusive. What is known is that in 1988 it was recovered in a tired and unhappy state by former Freshwater fireman Colin Piper. Together with his son Martin they laboured at personal expense and elbow grease to return the Shand Mason to the glory of its beginnings of 115 years before.

In 1994 when the Isle of Wight Fire and Rescue Service were planning the formal opening of the new Ryde Fire Station and Brigade Training Complex at Nicholson Road, Colin loaned the Shand Mason to the service to grace the entrance foyer of the training centre.

It remains there to this day, the first item of firefighting apparatus that the newest firefighter passes when arriving at the training centre for the first time - red, shining, in silent reverie of fires long since extinguished and firefighters long gone.

Below - former Freshwater fireman Colin Piper, appropriately attired and stood proudly alongside the Shand Mason that he and his son Martin lovingly restored. Photographed on the day of the opening of the new Ryde Fire Station and Brigade Training Complex, 10 May 1994.

If you enjoyed this article, you may also enjoy The Newsham Engine.

If you have enjoyed this page, why not make a small donation to the Firefighters Charity.