The Newsham Engine

The first two fire engines known to have served on the Isle of Wight were installed at Newport in the late seventeenth century, and at Cowes in the following century. Little more is known of the Newport machine, but a discovery in summer 2023 opened the door to a far greater depth of understanding of the Cowes engine (above), which I can now state to have been a model of the Newsham type.

In the wake of the Great Fire of London of 1666 the nation awoke to the need for organised protection from fire, an undertaking abandoned in any formal manner since the Romans departed these shores, circa 400AD. Whilst the need was recognised, Government was slow to act. I have discovered references to the Parish Pumpers Act of 1707, although no mention of it appears in any of the three publications I possess which proclaim to record the history of British fire service law.

When Bonhams, the London based auctioneer, sold a Newsham engine in 2003, the lot was accompanied by a description that referred to the Act, including a citation that stated - every parish was to have and keep in good repair a large engine – and that the churchwardens were to be encumbered with responsibility, one for which they could be fined if found wanting.

Despite repeated attempts and avenues explored to access a full transcription of the Act, I have been unsuccessful – even the London Metropolitan Archive produced no result. However, a reference to it was found on the Triskel Arts Centre website in a page dedicated to the Christchurch Parish Pump of Cork, stating - Under Queen Anne in 1707, the English Parliament passed a law requiring all parishes in London to have and maintain a large engine and a hand engine, along with a leather pipe to convey the water into the engine without the need for a bucket. However, this law only extended to London and not any other cities under British rule. Bonhams expanded their description with the claim that - The increase in production of manual fire engines in the 18th Century was mainly due to the introduction of the Parish Pumpers act of 1707. When the City of London was formed into a single civil parish by Act of 1907 (abolished 1965) it enforced the merger of over 100-parishes - a substantial market for fire engine manufacturers to embrace, as suggested by Bonhams.

Journalist, trader, and spy, Daniel Defoe (Fig.1) wrote of firefighting in London (1724) - Fires are extinguished by the great number of admirable Engines, of which every Parish has one … so that no sooner does a fire break out but the house is surrounded with Engines, and a flood of water poured upon it, ’till the fire is, as it were, not extinguished only, but drowned – suggesting that parish firefighting wasn’t an isolated undertaking and that cross-boundary support could be relied upon from neighbouring parishes.

From the above it can be estimated that the legislative application of the Act was most likely restricted to the City. However, it may have had an effect, albeit unenforceable, beyond the old Roman city boundary. Every reference I have found to Isle of Wight town engines of the pre-1800 era, refer to their stowage in places of worship under the care of those associated with the church, that being churchwardens, or in Newport’s case, the engine kept at St Thomas’s was in the care of the overseers of the poor.

Assuming that the 1707 Act placed no accountability on Isle of Wight parishes, it seems that for the lion’s share of the period following the Great Fire of London, and the establishment of formal non-insurance fire brigades in the nineteenth century, it was the rise of many fire insurance offices that filled the void. Fire insurance offices formed their own private fire brigades, serving many of the principal cities and towns across the nation. There is no evidence that the Isle of Wight ever fielded a fire insurance brigade, and the likelihood based on numbers of high value properties protected by fire insurance policies suggests it wasn’t commercially justifiable. But fire insurance offices did have some significant customers on the Island, and therefore a vested interest in protecting those properties to an extent commensurate with the financial risk to the company. For that reason, fire insurance offices made occasional financial inducements to parish authorities to promote a reaction similar to that enforced by the 1707 Act in London. We shall return to this aspect further on.

Bonhams’ suggestion that the Act promoted the need for the development, manufacture, and sale of fire engines appears logical. But who invented and built the first manual fire engine is subject to the opinion of several learned experts, with little agreement between them. What is less contestable is that one Richard Newsham of London either invented, or adapted existing fire engine design, by incorporating an engineering solution that revolutionised firefighting in the early eighteenth century.

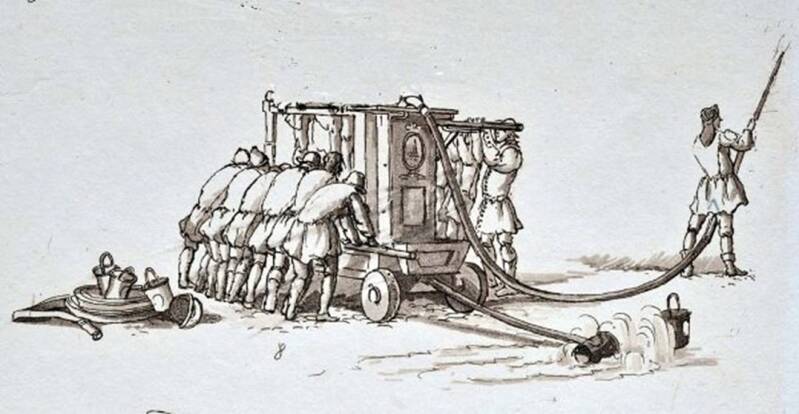

Fire engines of the era were cumbersome wheeled appliances normally transported by men rather than horse drawn. Described by a contemporary observer as a wheeled coffin, they were peculiarly narrow, not only for the streamlined negotiation of busy streets and lanes, but to allow the engine itself to be pushed through doorways.

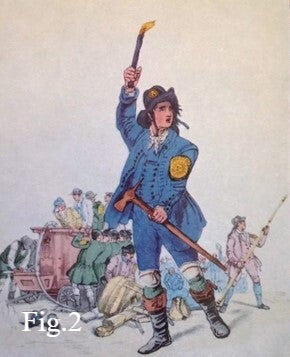

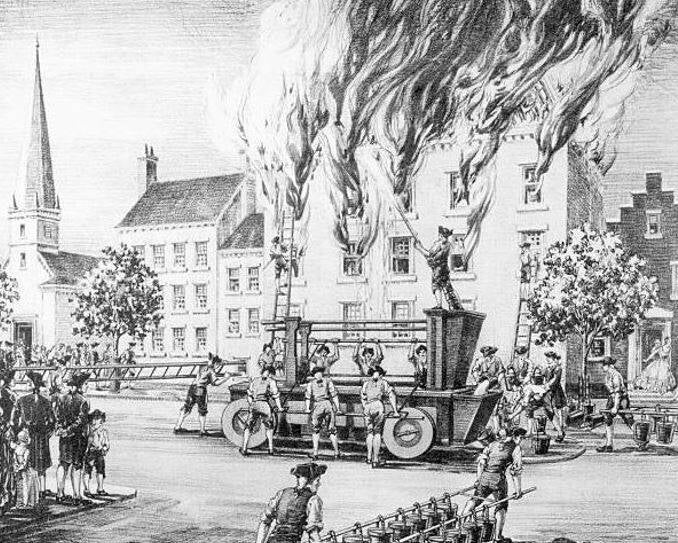

The image (Fig.2) shows a uniformed fireman of the Sun Fire Office, torch and axe in hand, leading the way while behind him a number of men operate a manual fire engine. These men are non-uniformed because they were not insurance firemen, and in fact would not have been employed by the insurers at all. Throughout the era of the manual engines successful deployment depended on the willingness of local persons to volunteer as manual pumpers. This particular image shows a row of men on either side, swinging the handles up and down in harmony, and above them a string of men standing in the middle of the engine itself, shifting their bodyweight left and right in sync with the handles, with their feet on treadles to assist the process. By all accounts this was an arduous and exhausting task that required frequent change arounds involving more volunteers.

This, coupled to the need for other volunteers to form a bucket chain to keep the body of the engine topped up with water from wherever the nearest source may be, suggests that many dozens of volunteers were required to deploy a single branch. It became commonplace for the volunteers to be recompensed after the event with a wet. In typically British fashion, in the knowledge that free beer was on offer there never seemed to have been any lack of volunteers. Over the course of time these handle swingers, effectively the power in the engine, created jovial songs to keep them in steady rhythm, some of which were allegedly of a crude and bawdy nature.

With the organisation of pumpers and bucket chains becoming a matter of local pride there was little issue with engine power, the problem came from the basic design of the engine itself. As the handle on one side was depressed, down went the piston and water would spurt from the branch, when it reached its maximum depth, water flow stopped. As the opposite handle was depressed, water would spurt from the branch once again, and so on in stop-start fashion. In some cases, where manual engines were equipped with a spout permanently attached to the top of the engine, and it was able to reach the flames, the effect would be negligible on the operators, if not deleterious to efficient firefighting.

Where it was pumped through hose, such as the leather studded example (Fig.3), anyone with a background in the fire service will be familiar with the recoil effect at the point that pressurised water first emerges from the branch. This is a key moment which can either be conducted with cool expertise or total failure, humiliation, and potential physical injury. For branch operators of the late seventeenth century the delivery of spurts of pressurised water must have been extremely difficult to manage, and probably not with great accuracy.

This would have proved tricky enough with a steady posture on a flat surface, it would have been much tougher for those clinging to a ladder or staggering upon a pitched roof. One of Newport’s earliest firemen, Ernest Hayles, was twice thrown from the roof of a building while operating a branch – and incredibly recovered from his injuries on both occasions.

Richard Newsham created the solution.

How a pearl button maker of Cloth Fair, Smithfield, London, became involved with fire engines remains an unanswered question, but he did, and in 1721, and 1725, Newsham submitted patents for engines to quench accidental fires. Although the patents themselves (Nos. 439 and 479) are meagre in detail, Newsham’s design was afforded substantial text supported by copper plate images in John Theophilus Desaguliers’ 700-page A Course of Experimental Philosophy (1744). John, born as Jean, was a disenfranchised Frenchman from a family expelled by the French government due to his father’s Huguenot leanings. Jean, or John (Fig.4), was a brilliant thinker who applied his philosophies to all manner of societies problems in addition to serving as chaplain to His Royal Highness Frederick the Prince of Wales.

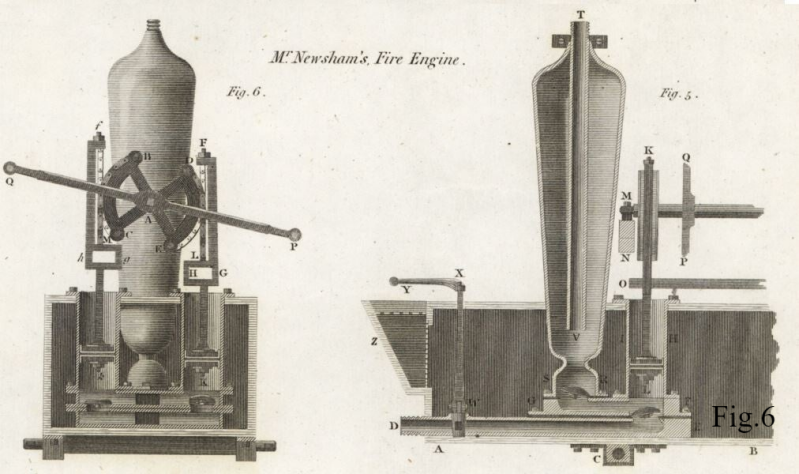

Desagulier clearly admired Newsham’s work, not because he was especially interested in fire engines or firefighting, but because Newsham had created the first engine that provided a continuous uninterrupted flow of water. Newsham’s design was as simple as it was ingenious.

The technical genius of Newsham’s design, shown in the extracts above from the original copper plate image, is more easily understandable by reference to the modern line drawing below (Fig.7).

In pre-Newsham manual engines, the downstroke of either handle of a manual engine forced water directly from the cylinder only when being compressed by the corresponding downstroke of the piston. Without piston pressure no water was expelled. Newsham introduced the air chamber into the equation to bridge the effect of loss of flow. The simple principle is that water cannot be compressed but air can, and air under compression creates pressure that can be utilised to maintain the flow of water at the points when the pumping handles are unable to. Piston A goes up with the handles, creating a vacuum which opens Valve B, through which water is drawn from the cistern of the engine, which required continual topping up by the volunteers of the bucket chain. The same action seals the cylinder by closing Valve C. As the piston returns down the cylinder, Valve B is closed, Valve C is forced open, the air chamber fills with water at a rate carefully calculated to be too great for it all to be expelled from Pipe E, thus creating compressed air at Point D, the expansion of which continues to dispel the remaining water from Pipe E even when Valve C closes and no more water is entering the chamber from that cylinder. Meanwhile the opposing cylinder is already on its way down and the process is repeated. This required greater exertion on the part of the volunteer pumpers, as they were required not only to apply pressure to water, but also compress the air in the chamber. The result was a smooth and continuous delivery of water to the sharp end of the operation – the branch. The branch operator was able to focus his attention on the task of fighting the fire with little fear of being thrown off his feet.

The crucial and simple success of this method compelled Desagulier to write – I cannot conclude this chapter of machines without giving the description of an engine for quenching fires, as they are now made in a very strong, well contrived, and workman-like manner, by Mr Richard Newsham, Engine-maker, living in Cloth Fair near Smithfield, London.

Desagulier continued with a description of the engine being seven feet high, and six feet from end to end. The cistern he described as constructed of well-seasoned English oaken planks near two inches in thickness and lined with sheet copper. Newsham’s engine sported a short length of leather sucking pipe for use on the rare occasion when the engine could be positioned close to an adequate water supply. It was at this point when reading Desagulier’s text that I was initially astonished, until realising that in the seventeenth century the letter ‘f’ was used to represent ‘s’, making a critical difference in the context of Desagulier’s use of suck, sucking, sucking-piece and sucking-valves.

With that awkward misunderstanding overcome, the text continues with the description that for use with bucket chains, water would be poured into a small trough, complete with copper grate to filter stones, which can be seen to the far left of the engine in Figure 4 of Newsham’s patent. Being placed at the end of the engine ensured that the exponent of the ultimate bucket remained clear of those furiously sweating over the handles.

Desagulier’s description goes into incredible detail, summarised by the line – it is my humble opinion that nothing can be altered in them for the better.

Common practice for the time was for manual fire engines to be manufactured to meet one of six standard capacities, as shown in the extract from Experimental Philosophy above. Desagulier states that for the six sizes, the following numbers of men are required to operate the pump – 8, 14, 16, 18, 22, or 24.

The Cowes Newsham model has been identified as in the upper-middle range, probably of the 4th type, delivering 150 gallons per minute, at a range of up to 48 yards from the spout, achieved by 18 volunteers.

Richard Newsham passed away in April 1743 a matter of months before publication of Desagulier’s glowing account of his work. His legacy improved fire brigades and their ability to fight fire for most of the next two centuries.

Like all historical researchers, I have made mistakes. One includes my assumptions concerning the provision of the Cowes Newsham fire engine. Many years ago, I discovered an article in the Isle of Wight County Press edition of 20 October 1962, which opened with – A picturesque study of St Mary’s Church, Cowes, which celebrates its tercentenary at the end of this month. The fifth paragraph of the article states – The chapel wardens added another important task to their usual duties in 1787 when they took charge of the care of the clumsy iron-wheeled fire engine, which was trundled along and operated by hand. This was presented to the town by the Sun Fire Office insurance company.

I assumed this to indicate that in 1787 the Sun Fire Office donated a fire engine to Cowes which was placed in the care of the St Mary’s chapel wardens. In summer 2023 I shared this assumption with the members of the UK Fire Brigade History group on Facebook. I received a comment by reply from a lady named Maureen Shettle. Maureen, as I was to discover, is the daughter of a late fire officer of Surrey who towards the later stages of his 30-year career served at the Fire Service Staff College at Wotton, followed by a move to Moreton in the Marsh.

Throughout his service and retirement, he was a keen fire service researcher who edited and produced most of the articles in the Surrey Fire History Trust magazine Vigiles. Maureen became involved in assisting him with sourcing historical references and found herself enthralled in particular by those involving the period of the fire insurance brigades.

Over a protracted period, Maureen attended the London Metropolitan Archives and transcribed original documents of the Sun Fire Office. She was able to inform me that there was no record of the Sun Fire Office having donated a fire engine to the town of Cowes in 1787. It was also her learned opinion that the Office did donate some fire engines, but these tended to be to the authorities of large towns or cities where a high value of insured property was present. Late eighteenth-century Cowes fell short of the criteria. However, Maureen identified several occasions when the Sun Fire Office made cash donations to Isle of Wight authorities to assist in the purchase of engines and equipment.

Most notable was a reference from 1765 in the Sun Committee of Management (Ms 11932/7). Dated 2 May, the minute stated - To the Town of West Cowes in the Isle of Wight £5.5s when they have purchas'd a Fire Engine pursuant to their Request. Two months earlier the Salisbury and Winchester Journal carried an advertisement for an auction to take place on the 26 March. Ordered by the Assignees, suggesting a case of insolvency, the household goods and stock in trade of East Cowes shipbuilder Isaac Mitchell was to be sold under the hammer. The advertisement listed many items in the inventory, including – a very good Fire Engine and Buckets.

I can’t imagine that in the late eighteenth century there were a plethora of second-hand fire engines on the market. It can’t be proven, yet, but it is feasible that West Cowes heard of Mitchell’s lot at East Cowes, and, possessing a significant number of properties insured by the Sun Fire Office, appealed to them for assistance to provide the town with a contribution towards its first fire engine. At present it is just a theory, supported by the suggestion of the engine being very good, as Newsham’s pumps were the cutting edge of fire service technology during the era in question.

It was far from unusual during the era of the fire insurance offices for them to make contributions to fire protection. In areas where an insurance office provided policy cover to some valuable property, but insufficient to justify the expense of establishing an insurance brigade, it was wise for the insurance office to support and at times motivate the local authority into action, with an occasional financial incentive. In 1784 Cowes received 20 guineas towards more equipment, and in November 1821 purchased and despatched a length of hose needed for the engine.

In July 1760 the Sun Fire Office minutes record that - an Engine of the third size with a proportionable length of Pipe and two dozen of Buckets be sent to the Agent in the Isle of Wight to remain under the care of the Agent for this office for the time being.

It remains a mystery as to where this engine served, if anywhere. Similarly unexplained is the record of the following June - To Richard Ragg £49.15s for a third size Engine with Suction Pipe & three dozen of Buckets sent to Mr John Jacob, Agent in Newport in the Isle of Wight.

What is known is that the Newsham engine belonging to the early Cowes Fire Brigade was accommodated in a small structure near the park gates on Park Road. Writing in 1968 a contributor to an article that appeared in the IW County Press stated that the building, featuring a circular fanlight above the doors, was still present and used as garage by the occupiers of Windsor Cottage, Inside, the hooks formerly used to suspend the firemen's kit, remained in place. Sadly the building appears to have been demolished since 1968.

The following reference from August 1804 is self-explanatory - Town of Newport, Isle of Wight, towards an Engine £40. Followed by a record of the Globe Insurance Co., in September 1905 that stated - Resolved that the following contributions towards purchasing Engines for Country Towns and Donations of Buckets to Agents be given. Newport - Towards Engine £10 or two dozen Buckets but the contribution for the Engine not to be given unless an Engine is to be provided. The final Isle of Wight reference by the Sun Fire Office Committee of Management made a record of a contribution in 1829 that ties in perfectly with the date of the establishment of Ryde Fire Brigade, the first organised brigade on the Island - Resolved that £10 be subscribed towards the purchase of an Engine at Ryde provided arrangements are made by the Town for keeping it in repair at their expense.

Newsham’s engines were so successful that they received interest from across the world. In December 1731, the Beaver arrived at New York from its Atlantic voyage, where two Newsham engines were unloaded. Being of the fourth and sixth sizes, these were at the larger end of the scale, as ordered by the New York Common Council. The engine was named the Hayseeds by the men of Engine Company No.1, New York’s first engine department. Later in the service of the engine, the men that operated Hayseeds, were known collectively as The Old Guard, as they also served in a home guard capacity under the command of General George Washington, although he delegated command at fires to a chief of the fire department. However, Philadelphia claim to be the first American city to field a Newsham, of the 4th type, in 1730, followed by Salem, Massachusetts in the 1740’s plus Williamsburg in Virginia.

The latter model was entirely deconstructed for analysis, documentation, cleaning, and structural stabilisation in 2008. During this process nine coats of paint were carefully peeled away, revealing the original ‘Newsham & Ragg’ lettering on the side, dating the engines manufacture between 1744-1765. It also revealed that the air chamber had been replaced by one installed by Hadley, Simpkin & Lott in 1830. As with the same model in Cowes, it appears that this engine served for well over one hundred years. One of the earliest purchases of a Newsham engine, kept at St Michael’s Church in Bray, Berskhire, was maintained and actively used for firefighting purposes across the parish for over 200-years.

The last remaining original New York Newsham engine, displayed at the Firefighters Association of the State of New York, Museum of Firefighting, Hudson, County Colombia.

By the time Cowes acquired their model, Newsham had been dead for over twenty years. His will bequeathed the business to his son Laurence, who also died in the following year. In turn, Laurence willed the business to his wife and his cousin George Ragg. The pair were married and business retitled Newsham and Ragg. Around the time of Cowes’ acquisition, the business was taken over by John Bristow of Church Lane, Whitechapel. He built and sold engines under his own name, but the design and technical advantages created by Newsham remained the core appeal of Bristow’s engines.

Evidently the Cowes Newsham engine enjoyed a long service in the town but the first press report of the Newsham engine in action was recorded by the IW Observer in 1853. Reflecting on a devastating fire at Debourne Lodge on 13 December, the Observer remarked that the engine was operated by a number of by-passers and a detachment of soldiers, this being prior to Cowes forming an organised fire brigade. In the following September the engine, being run down Market Hill by volunteers keen to get to grips with a fire at a coach house, overran the exponents, crushing two of them beneath its wheels with serious injuries sustained. In the aftermath of this fire the injured men were compensated, but William Floyd, who had taken charge of the engine once safely at the scene, was later fined for his actions after the event. Dissatisfied that he hadn’t received a penny for his efforts he entered a shop near Carvel Lane and threatened the man he believed was dealing with payments, waving a knife under his nose and stating, ‘you b-----d, I should like to dig your grave for you’. His threatening demand for a shilling cost him almost double that amount at the adjudication of the magistrates.

On 5 April 1856 the Newsham engine was present at a major fire at John and Robert White’s shipbuilding yard that is marked in history as the first occasion that an Isle of Wight fire was attended by crews from Hampshire. The threatening conflagration attracted the attentions of the Newsham of Cowes, White’s own company engine and that of Newport. The sight of the flames from across the Solent was sufficient for Portsmouth to despatch five of its engines to Cowes to assist. The IW Observer estimated that between 500-600 local men voluntarily served at the fire.

Over the course of the next forty years the engine attended a steady stream of fire incidents, becoming more proficiently operated following the formal organisation of Cowes Fire Brigade, circa 1880. By 1896 the question of the engines suitability and maintenance was being questioned at Council, the machine by then having served for over 130 years. One scheme suggested selling both it, and the hose-reel cart, to fund the purchase of a new machine, but money for the new machine was found without the loss of the former. In January 1898 the Newsham engine, appeared diminutive behind the new engine when the brigade put on a display at Victoria Parade (Fig.8).

After the turn of the century, the decision was made to retire the Newsham as it reached its 140th year in service. The initial plan was to scrap the engine, for which purpose a photographer captured its image for posterity (shown at the top of this page). However, parties with an interest in the town’s heritage managed to save the engine as an antiquity and it was placed in the Town Hall basement for safe keeping.

Sadly, despite research for information to the contrary, the only logical conclusion, alluded to by a County Press article of 1968, is that it was destroyed by enemy bombing during the infamous Cowes blitz of 4/5 May 1942.