In 1996 my research into the history of the fire service, and by default the wartime civil defence service, was compelled by the discovery of an unpublished diary written by a teenaged fireman who served in the same town as the one to which I had been recruited more than fifty years later.

Discovering that the reason for his diary ending so suddenly was due to his death in a sustained aerial attack on the northerly point of the Isle of Wight in May 1942, I was compelled to understand what he was doing, how he died, and who killed him.

For many years my research took a sideways trajectory, discovering more destruction, tragedy and death wrought from the air. It was the chance discovery of another unpublished diary, and its meticulous translation from German to English (Enemy of the People), that offered a step forward in understanding the originators of the Luftwaffe attacks on parts of this island home that I have been fortunate enough to enjoy in more peaceful times.

In pursuit of more detail, and by a lengthy path, researching the contents of the National Archives in the hope of finding a document relating to the death of twelve members of the National Fire Service by a single bomb barely seven miles from my home, I stumbled across document RE/B/16/21/2 - Air Raid Damage – No.6 Region – Shanklin I.O.W. – 3.1.43 – Bomb No.4 at Gloster Hotel.

RE was abbreviation for the Research and Experiments Department of the Ministry of Home Security. Over the course of the following four years, I extracted more R&E files of a similar matter.

Each file, differed in content, but evidenced a similar pattern, and these I have used to substantiate with facts the matters concerning several raids located elsewhere on this website.

The reports were submitted by investigators, who appeared to have been in the employ of the constabulary, after they had been dispatched to the site of a raid to record details of the effect, always accompanied by facts, figures and explanative text, and sometimes including photography, sketches, maps, and plans.

Particular emphasis was placed on facilities provided for civil protection – Morrison table shelters, Anderson shelters, surface shelters, trench shelters. I was therefore convinced that R&E’s role was to report on the efficacy of protective measures.

I wasn’t incorrect, but their entire role was so much more. I discovered a reference to Mr A.R. Astbury and his written work The History of the Research and Experiments Department, Ministry of Home Security, 1939 – 1945. I typed the title into a Google search bar and expected to instantly find a copy – if I had, I may have dwelled on it and revisited it later. The fact that it seemed impossible to find motivated me to find out why.

Faithfully returning to the National Archives, I wasn’t to be disappointed. There it was, over 170 dog-eared typescript pages in a buff folder marked for closure until 1972.

A.R. Astbury, CSI, CIE, M.Inst CE, was a Technical Adviser at R&E. He had lived and worked through the departments evolution and decided to produce its fascinating history for publication. Evidently it was ready for final pre-publication editing around 1947 when it was decreed too sensitive in nature and locked away until my first school year in the early 1970’s.

I wondered, given the journey I had taken to find it, and its evident lack of exposure in a world of high-speed digitised access to virtually anything, if I was the first to open the folder in earnest since it was officially unlocked at a time my shorts-clad legs were dashing about West Street schoolyard to the cry of British Bulldog.

Due to the book not being published, no biography of A.R. Astbury is included. By means of online genealogical research I discovered a few notables by that name and from these I am confident I have identified the correct man.

Born on 5 June 1880 and baptised at St. Mark’s Chapel, London, Arthur Ralph Astbury studied at St. Peter’s College, Westminster from 1894-1897 and undertook scientific training at the Royal Indian Engineering College at Coopers Hill, Egham, 1897-1900, before being proposed for membership of the Institution of Civil Engineers on 28 July 1906 while resident in Lahore. Five months later he relocated to Torrentium Cottage, Shimla. He married Friede Hildegard Vonschonberg at Bengal, in 1908. They were to have to two children, John and Elinor.

On 2 January 1933, he was appointed as a Companion to the chivalric Order of the Star of India, proclaimed by Queen Victoria in 1861 as follows - The Queen, being desirous of affording to the Princes, Chiefs and People of the Indian Empire, a public and signal testimony of Her regard, by the Institution of an Order of knighthood, whereby Her resolution to take upon Herself the Government of the Territories in India may be commemorated, and by which Her Majesty may be enabled to reward conspicuous merit and loyalty, has been graciously pleased, by Letters Patent under the Great Seal of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, to institute, erect, constitute, and create, an Order of Knighthood, to be known by, and have for ever hereafter, the name, style, and designation, of "The Most Exalted Order of the Star of India".

In 1938 he returned to England. When the 1939 Register was taken in the following September he and Friede were located at a property named Amesbury in Wycombe, just seven miles from Princes Risborough, the relevance of which will be revealed below. Among the four others sharing the address at the time of the enumerators visit, one was a Technical Assistant to Research Laboratory, and Mr. Astbury himself, by then 59 years of age, was working as a Civil Engineer. In Column 11 of the record, further detail is provided, which, with a little difficulty, appears to read – Tech. Admin. ARP Dept. Home Office.

Given that the discovery of his post-nominals and the matching appointment to the Order came from two distinct sources, coupled to the content of Column 11 of the Register and his residence close to Princes Risborough, I’d bet my house that he is the author of the R&E history.

The contents of Mr. Astbury's manuscript opened my eyes to an organisation that did much more than accumulate post air-raid statistics. There doesn’t seem to be any aspect of protecting British society in wartime that R&E didn’t touch in a positive manner. They were the reasoning behind Civil Defence, aka Air Raid Precautions. Lives are saved by heroes, so they say, Astbury’s manuscript, without any deliberate attempt to do so, truly supports the counter that not all heroes wear capes, some wear laboratory coats.

What follows is a condensed appraisal of the salient points of R&E's history as recorded and written by Arthur Ralph Astbury.

Air Raid Precautions (Civil Defence) and the creation of R&E

T.H. O’Brien’s 700+ page authoritative account ‘Civil Defence’ reveals that the need for organised methods of protecting the civil population from enemy aerial bombardment was formally considered as a national effort by the Committee of Imperial Defence in 1924.

During the First World War over 50 attacks by airships in addition to those by Gotha bombers and the Zeppelin-Staaken R.VI four-engine biplane bomber known as the Giant, proved to be British society’s first experience of war on home soil since the failed French invasion of 1797 (Battle of Fishguard). Despite the best efforts of the Committee of Imperial Defence, little of a formal nature was concluded until the government issued its first official circular on the matter on 9 July 1935; advising local authorities that Government would issue general instructions on civil defence based on expert study of the associated matters – but little had actually been analysed to substantiate the intent.

Aviation development went into overdrive after the war to end all wars. As much as flight appealed to the affluent in terms of travel and sport, inevitably it was harnessed for military purposes. Theories abounded of what military aviation could accomplish, none of which prepared people of the free world for the news that emerged from the Spanish Civil War (1936-39) and in particular the ferocious bombing of the undefended people of Guernica by a combined air force of German and Italian fascists.

Guernica was all but destroyed on 26 April 1937. In the same month 800,000 volunteers were sought to create the UK’s Air Raid Wardens Service. In December the same year Royal Assent was granted for the Air Raid Precautions Act which became effective on New Years Day 1938. By the middle of the year just a quarter of the required number of wardens had signed up. In the wake of the Munich Crisis in September, a sudden influx boosted the figure by an additional 500,000 volunteers.

Despite the issuing of guidance to the public (the first handbook was published in 1935) based largely on the theoretical considerations of the Bombing Tests sub-committee of the Committee of Imperial Defence and the Home Office Structural Precautions Committee, it wasn’t until February 1939 that the need for greater depth of knowledge through tests and trials culminated in the formation of the Research and Experiments Department of the Home Office, and shortly after being relocated beneath the wing of the Ministry of Home Security.

Within his 700 pages, O’Brien, without citing R&E, alluded to the scope of their influence when he wrote – The reader may be surprised, for instance, at the relatively small proportion of the volume devoted to description of air attacks. The reason is that much more time and effort were spent on preparations for large-scale bombardment than on dealing with the consequences of the bombs themselves.

A substantial chunk of that time and effort was the work undertaken by R&E.

Sir (Dr.) R.E. Stradling, Head of Research and Experiments

Working under the direct oversight of the Civil Defence Research Committee, Research and Experiments brought together some of the nation’s most brilliant minds from a diverse range of professional fields and melded them into the most effective and influential force for change that the nation has ever known. The work they undertook amid the haste with which the outcomes were desired, is unparalleled.

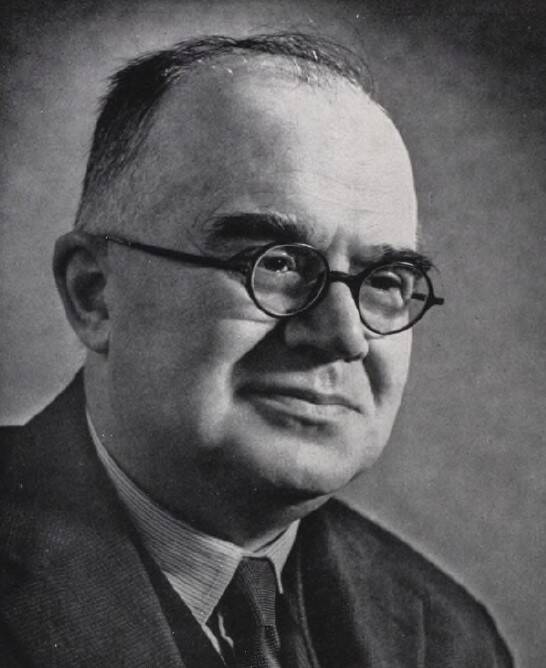

The man placed at the head of such a vital department was Dr. Reginald Edward Stradling (later ‘Sir’).

Born in Bedminster, 1891, Census records of the late Victorian period evidence that Reginald’s father was a baker, and later a corn and forage merchant. This suggests an unostentatious upbringing. Nevertheless, Reginald aspired to be a physician, an ambition thwarted only by extreme short-sightedness. Instead, he won a scholarship to Bristol University and graduated with a BSc in Civil Engineering. At the outbreak of war Reginald was commissioned into the Royal Engineers and served with distinction, mentioned in dispatches twice and awarded the Military Cross.

Post-war he obtained a post as lecturer in Civil Engineering at the University of Birmingham, before moving to fulfil the role of Head of Civil Engineering at Bradford Technical College in 1922. Two years later he took up the post of Director of Building Research, experimenting on building and road construction. There he remained until 1939 when he was appointed as the head of R&E. His knighthood was received in 1945 in respect of his wartime endeavours – being one of many honours granted both at home and from institutions in America.

Reginald passed away in January 1952, his friend and colleague at R&E, A.J.S. Pippard, summarised an obituary in a civil engineering journal – Stradling’s life was marked by devotion to his work and to his family, and those who were fortunate enough to be able to claim his friendship will ever be grateful for that privilege.

Beginnings, Structure and Evolution of R&E

Before the R&E Department was established, decisions based on theoretical findings by the Bombing Tests and Structural Precautions committees, had compelled some decisions to be made in areas that R&E would imminently inherit. The stirrup-pump, Anderson shelter, trench, basement and surface shelters, and the concept of refuge rooms in dwellinghouses were well advanced, but above all else it was investment in time and materials for protection from war gases that took precedence.

As the scope of the requirement widened, so too did the committees, sub-committees and disparate institutions that emerged in response. The disadvantage of the system of separate agencies was that the ARP Department had priorities, but little control over the focus of the myriad of agencies upon which the work depended, each of which had their own primary interests to attend to. Coupled to this it was suspected that some protective measures being manufactured and marketed commercially, were not fit for purpose, and in the event of aerial attack would not materially reduce loss of life and instead create general panic amid the environment into which emergency elements of the ARP and fire services would respond. A method of standardising and approving commercially available items was required.

Dr. Stradling, serving as the Director of Building Research, was consulted by the Home Office in late 1938 to survey the position and advise on suitable measures. His report led to the establishment of the Research and Experiments Department on 13 February 1939, accommodated at Westminster’s Horseferry House.

Three weeks earlier, Dr. Stradling was appointed as Chief Scientific Adviser of the fledgling department. Reporting directly to the Deputy Under-Secretary of State, Dr. Stradling’s responsibilities were supervision and coordination of all work carried by, or on behalf of R&E, across a wide, and continually evolving range of civil defence matters.

Even with a modest initial staff of 24, it was immediately apparent that R&E’s ability to function was restricted by lack of capacity at Horseferry. By the end of March 1939, they relocated round the corner to Cleland House in John Islip Street, close to the Lambeth Bridge.

Government was considering the option to evacuate elements of the administration to low-risk areas outside of London. Departments and offices that were able to function to full capacity outside the city were prioritised. In addition to meeting the criteria for priority evacuation, R&E were already straining at the seams at Cleland. In April 1939 arrangements were made to relocate to the site of the Forest Products Research Laboratory at Princes Risborough, Buckinghamshire – about 30 road miles west of Watford.

Work began on the relocation in earnest, including billeting for staff, but R&E didn’t fully encamp at Princes Risborough until August, when, on the 25th, with war considered imminent, all leave was cancelled. The Cleland House offices were formally closed on 1 September while on the continent Germany was invading Poland. R&E, with an increase of permanent staff to 110, was placed on a war footing.

Dr. Stradling’s earliest appointments were his senior team, including Arthur Ralph Astbury, drawn from the Chief Engineering Adviser’s Branch to serve as R&E Technical Adviser. Stradling and Astbury were joined by five additional appointees to form the R&E headquarters staff.

HQ staff oversaw the work of the full-time advisers, grouped by subject, fielding many of the nation’s most eminent doctors, professors, and professionals across the range. The full list of sections, sub-sections, committees, sub-committees, and panels forms an incomprehensible list of brilliant minds. Dr. Stradling’s task was to create a workable structure.

By early summer 1940, the work of the department had expanded exponentially, compelling not only a strategic move from the Home Office to the Ministry of Home Security, but the redistribution of resources across a range of twelve definitive Sections. Each Section possessed its own accountabilities and responsibilities, but in many experiments overlapped and worked alongside other Sections to achieve the desired outcome.

R.E.1 – General Administration

Staff appointments, billeting, supplies, processing leave and travel claims, staff cars and petrol coupons, telephones, and all matters connected to expenditure.

R.E.2 – Control of Research

With the exception of matters connected to chemical and camouflage, R.E.2 was responsible for oversight and supervision of every research programme. Any other Section requiring tests or investigations be carried out were to first seek sanction from R.E.2.

R.E.3 – Chemical Research

Chemical research was wide and varied but concentrated principally on matters connected to war gases – detection, protective clothing, respirators and materials, decontamination, protection of foodstuffs from war gases, air filtration for shelters, anti-gas ointments – in addition to sandbag preservation, paints for road marking, firefighting foams, and associated Home Office certification and mark schemes.

R.E.4 – Technical Development (other than chemical)

R.E.4 focussed on window protection, structural alterations in vital factories, protection of plant, ventilation of shelters, advice on materials and shelter schemes, and drafting of handbooks and memoranda for publication.

R.E.5 – Electrical

Security of electricity supply, protection of electrical plant, distribution, and use of electricity.

R.E. 6 – Technical Intelligence and Liaison

R.E.6 was responsible for the network of officers that conducted post-raid fieldwork, Regional Technical Investigating Officers and subordinate TIO’s, those being the individuals that attended the sites of air raid attacks to produce reports (as featured in the relevant pages of this website). In addition, R.E.6 worked with foreign intelligence, Passive Air Defence (PAD) sections of other government offices, and in the production and filing of publications and records.

The above six Sections of R&E were augmented in 1941-42 by the addition of the following.

R.E.7 – Fire Research

R.E.7, also known as ‘F’ Division, dealt with all matters relating to fires, fire protection and firefighting, most notably in response to the German use of mass incendiary devices dropped from the air.

R.E.8 – Appreciation (from November 1941)

R.E.8 was formed in November 1941 to study the general effect of air attack on structures. Eight months after formation, its role was amended to that below.

R.E.8 – Operational Research (from July 1942)

The main thrust for a shift in focus of R.E.8’s role, was the benefit to the fighting forces of knowledge gained concerning the effect on structures of various bombs and bombing techniques. Turning conclusions of defensive investigation into useful data for offensive purposes brought R.E.8 into the fore and compelled liaison with Air Staff, the Admiralty, and the War Office.

R.E.9 – Armaments (from March 1942)

R.E.9’s responsibilities were many, centred on the theme of identifying enemy armaments, operational and feasible use, and assimilating understanding for offensive interests. Additionally, R.E.9, having been granted use of an outbuilding at Princes Risborough, accumulated bomb fragments, many of which were rebuilt in full, and displayed in what was effectively a museum of great operational interest to many parties. As a consequence of this, and the Section’s expanding technical knowledge of the subject, lectures were delivered to Ministry of Home Security schools and civil defence establishments. The Section also generated and distributed Enemy Aircraft Armament Notices to field staff and other interested departments.

R.E.10 – Lighting

The Air Raid Precautions Act 1937, made it incumbent on the nation to restrict lighting, reinforced with greater detail in the Lighting (Restrictions) Order 1939. R.E.10 worked to formalise this need and with the British Standard Institution established a number of specifications within the BS/ARP series. This involved the provision of lighting for large industrial complexes vital to the war effort, through the range of commercial and dwellinghouse needs, through to handheld torches and bicycle lights – plus responding to public queries connected to lighting, in particular ventilation of homes during the blackout.

R.E.11 – Publications and Records

R.E.11 were effectively the librarians of all documents generated by, or required by the department.

R.E.12 – Statistics

Enumeration of bomb explosions and casualties. Evidencing the relationship between bombing, casualty numbers and dispersal of persons to inform future evacuation and shelter planning.

R&E Sections at Work

Mr. Astbury’s reflection of the work of the R&E Department was represented across 20 chapters, beginning with several dedicated to its roots, formation, and responsibilities, before revealing the work and outcomes achieved across the various subjects. What follows is a precis of the salient points.

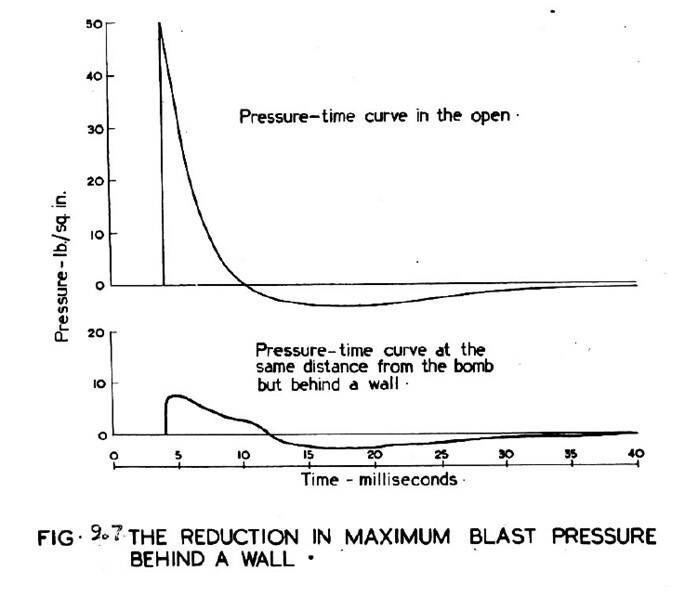

Chapter 9 of the history of R&E, ‘Physics of Explosions’ provides a substantial explanation of the factors of exploding bombs and how they were studied in both theory and practice. Acknowledging that an ounce of TNT contains roughly the same energy as the same mass of coal, and that the only difference is the rate at which the energy is released, Astbury describes the practical and theoretical analysis undertaken to understand the effect of blast, shock-wave (positive and negative), and earth-shock.

Most of the initial practical testing was conducted using the British 500 lb. G.P. bomb. For this purpose, the department co-ordinated works undertaken on its behalf involving the Building Research Station at the Bucknalls estate near Watford, the Road Research Laboratory (a branch of the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research where a ‘blast tunnel’ was constructed) – both of which accommodated Barnes Wallis while testing his bouncing bomb theory – and the Research Department at Woolwich.

Small-scale practical experiments were conducted in the open at BRS and RSL. These were undertaken to study the effect of blast on structures including within confined spaces to determine the integrity of partition walls in basement shelters. R&E developed the theory behind the need to provide screening of surface shelters, most commonly seen in the ‘L’ shaped entry points into both civil and military sheltering. Advice was also issued to owners of Anderson shelters to erect similar. Most assumed this to be a method of preventing flying debris from direct entry, in fact it was more closely related to preventing the introduction of blast wave and a rise in pressure capable of throwing persons about and lifting the roof from the shelter.

British 500 lb. General Purpose bomb

It was noted during trials that use of the G.P. bomb was in itself producing varying results due to variation in bomb casing, detail of fusing, and the manner in which the explosive charge occurred. From there on the use of bare charges of measurable mass and dimension were used. This had the added benefit of reducing the risk represented by bomb fragments. The use of constructed bombs restricted tests to the Ministry of Supply Experimental Establishment at Shoeburyness on the Essex coast, where the limited capacity was in great demand. Bare charges allowed the use of facilities at Stewartby in Bedfordshire, the home of the London Brick Company, and Richmond Park. Live explosion testing was maximised by cross-Section collaboration and in this way the primary effect of testing the effect of an explosion on a structure was often accompanied by tests on protective measures, such as helmets, ear defenders, and armoured components.

Under stringent procedures, of recovery, transportation and execution, unexploded German bombs were tested and compared with British ordnance.

Naturally, adaptation of shelter design was influenced by the results of the explosive trials. One exception was the Anderson shelter, designed and distributed before the launch of R&E, the department found little fault with its application, both in tests and from field investigations of post-raid sites. R&E were equally favourable of the Morrison table shelter, and field investigations, including some on the Isle of Wight, evidenced the incredible robustness of these tiny shelters in dire conditions (see the incredible survival of Elsie Thorpe of Ventnor, 1 April 1943, in the associated R&E report and photographs HERE).

The study of the effect of earthshock on the integrity of basements and other below ground shelters was another example of cross-Section collaboration, in addition to which was added the skills of the Building Research Station.

In the last day of September 1941, the Martin family of Sunderland had a miraculous escape thanks to the integrity of their Anderson shelter, placed just a few yards from the rear wall of the family home that took a direct hit and collapsed upon them. The most remarkable thing is that this event is rare for being photographed soon after it occurred, but reports of this kind involving Andersons was not uncommon.

In Astbury’s words – As the effect of earthshock was known to be influenced by the nature of the soil between the bomb and the shelter, it was necessary to carry out full-scale experiments at selected places where typical soils existed. The principal tests were conducted on the chalk soil of Larkhill on Salisbury Plain, and the sandy loam of Blackbank near Carlisle. Piezo-electric gauges with oscillograph units were used to record measurements.

Unsurprisingly it was discovered that the rate of earth movement in sub-surface explosions was considerably less than that of air displacement when exploding on or above the surface. However, the force of mass earth movement rendered existing pre-cast sub-surface shelters vulnerable to collapse through inward movement of a wall, leaving roof members unsupported, or the roof members being lifted, leaving the walls unsupported and pushed inside the shelter by the earth. Even lengthy trench systems of a similar build, which were thought to afford added integrity by the provision of compartmentalisation, were shown to collapse throughout when subjected to the same reaction.

By chance of testing, R&E discovered that surface shelters which were nominally afforded a damp course, suffered a particular vulnerability in that a blast insufficient to destruct the walls, would literally slide the structure off the damp course. In response R&E designed a pre-formed concrete box-form of shelter that was designed to slide as a whole, thus absorbing the energy of the blast without catastrophic effect. They also proved that existing surface shelters could be modified with a course of hessian impregnated with bitumen emulsion that greatly reduced the potential for sliding.

Glass, as a secondary effect of blast, was an evil capable of inflicting vicious wounds on those nearby. Prior to the launch of R&E the Structural Precautions Committee issued a public advisory booklet ‘The protection of your home against air raids’, in which they implied the barricading of windows with sandbags, in addition to the method of taping panes – collectively such measures were known as anti-scatter.

R&E utilised the blast tunnel at the Road Research Laboratory to test these and their own theories. Windows, frames, and similar structures were subject to blast created by the explosion of a small balloon filled with an electrolytic mixture of hydrogen and oxygen. Tests of this nature were also carried out on commercially available products.

Many householders were reluctant to follow some of the official guidance which required the whole, or partial, covering of their windows and the consequent reduction in daylight, and were attracted by, in particular, a simple application of a lacquer, sold in bottles. These were found to pass the test when freshly applied.

However, R&E’s diligence proved that after just a few weeks of exposure to the elements, the lacquer failed catastrophically. Accordingly, no such treatments were approved unless they had passed a minimum period of four-months effectiveness and that commercial advertising highlighted this fact.

The Building Research Station regularly updated and published a list of approved methods and treatments for providing anti-scatter solutions. As access to suitable materials to manufacture treatments on the approved list became difficult, unapproved commercial treatments were prohibited from production.

The problems of anti-scatter in a domestic environment were multiplied when addressing glazing in the commercial world, and that of vital industries that operated in factory buildings with roof lights. Various bracings and reinforced framing were trialled and tested, but resulted in the unsatisfactory result that improving the integrity of glass in the frame only increased the likelihood of the frame and glass as a whole being ejected at speed from the aperture. Such adaptations were substantial and costly in terms of material and manpower, leaving Mr. Astbury to conclude – such systems have no practical value.

What is especially interesting concerning R&E’s operations, is that they were as willing to engage directly with public opinion as much as with concerns emanating from authority. The effect of glass in the early bombing campaigns was a profound example, as casualty numbers were greatly increased by the number of those injured by high-speed fragments of glass. Mr. Astbury reflects that it was queries from the public concerning the potential for replacement of glass with a less brittle alternative that compelled a new line of inquiry. If everyone had consistently re-glazed at once, window glass might have become scarce… ingenuity was shown in pressing into service such makeshift materials as galvanised steel sheet, linoleum, tarred felt, cardboard, varnished cotton fabrics, plasterboard, and even oiled paper. If some of these kept out daylight, at least they made the blackout easier.

However the commercial world was quick to seize on an opportunity, and a variety of alternatives swamped the market. In September 1940, R&E collected a total of 360 samples from the marketplace and began trials. From the perspective of manufacturers, many of whom willingly sent samples of their product for testing, R&E in undertaking its wartime remit, were providing a free testing and approval service. The hundreds of samples were grouped into five categories, (i) Plastic film with metal reinforcement; (ii) Plastic film with textile netting reinforcement; (iii) Plastic film without reinforcement; (iv) Impregnated fabrics; (v) Waterproofed papers.

All samples were first tested to exposure of natural conditions before moving on to the blast stage – which some did not achieve through process of delamination. The outcomes, which would have been of great interest to the inquiring public, were rightly subjected to a comparative cost/performance factor. Eventually 130 of the original 360 samples received departmental certification.

Lighting was another subject that took up a substantial amount of time and resources. The ARP Act 1937 made it incumbent on the Home Office to issue regulations regarding lighting restrictions – the Lighting (Restrictions) Order 1098/1939 was the result.

The Order required complete screening of all interior light and reduction of exterior lighting to the absolute minimum necessary for the continuance of work of national importance. In addition, Section 43 of the Civil Defence Act placed the responsibility on the occupiers of factory premises and owners of mines, to obscure internal lighting and extinguish external lighting except where proven to be of vital need.

R&E found that attempts to experiment with lighting by aerial surveillance was fraught with several disadvantages, both technically and practically. With specialist assistance provided by the Research Laboratories of the General Electric Co., a laboratory method was designed using dual projection lanterns. The National Physical Laboratory also contributed with ideas and tests of their own. In all, 14 standards were issued in the BS/ARP series related to lighting. As with other pro-active measures, the needs of the nation’s safety were finely balanced with the desire for as much of normal life to continue. This ethos runs like a vein through all of R&E’s considerations, proving by test and technical analysis that contrary to the opinions of some, Government wasn’t locking down society unnecessarily.

The Street Fire Party's evolved into the Fire Guard Service which became a vital element of fire protection arrangements.

The study of fires advanced into previously unknown territory, as summarised by Mr. Astbury – In peace-time fires are not expected to break out simultaneously in many places in a town, but an incendiary attack from the air may aim at starting so many fires at once that the fire services will lose control.

Hence the focus of fire research was not regular firefighting, but rapid prevention of the growth and spread of incalculable numbers of small fires on a broad front. It’s notable that this work began prior to the August 1941 launch of the National Fire Service. There is no question that officers and men of the disparate local brigades and units of the Auxiliary Fire Service committed themselves heroically during the attacks of the pre-NFS era, but in tactical and strategic terms the nature of the hastily assembled conglomerate was part of the problem. That’s not to suggest that creating the NFS solved the problem overnight, it didn’t, but it did provide the foundation upon which the wider solution was laid – the Fire Guard Service and its forerunner the supplementary (or ‘street) fire parties (SFP).

In addition to testing, trialling, and advising on the issue of equipment and firefighting medias most effective to fire services and SFP/FGS units, R&E became the authority on the subject of German incendiaries, most notably the 1kg cylinder type. As R&E and the civil defence services developed effective and surprisingly unfussy methods of dealing with incendiary bombs at the incipient stage, the enemy introduced new elements – the Incendiary Bomb Exploding Nose (I.B.E.N.) and Incendiary Bomb Separating Explosive Nose (I.B.S.E.N.). Understanding of these bombs, their construction and distribution, was aided by troops in the Middle East seizing a German technical instruction dated 9 July 1942 (although I.B.S.E.N was not dropped on the UK in any quantity until 1944).

Astbury’s book revealed the voluntary recruitment of a Corps of Honorary Fire Observers. At ‘F’ Divisions request, the Corps of HFOs were an assembly of scientific and technically qualified men, mostly occupying senior posts at universities and in industry, who were willing to attend and study the behaviour of fires as they developed. Lines of study were not prescribed, deliberately allowing the learned professionals to make their own approach and study lines of interest they discovered.

The National Fire Service College, Saltdean, with the NFS standard flying above the requisitioned Grand Ocean Hotel.

Arrangements were made for NFS control rooms to advise the HFO of developing situations. Contact between Churchill’s Heroes with Grimy Faces and the professional academics of HFO was reported to be good and of mutual benefit. The willingness and capability of these highly qualified men to communicate with the grass roots of the fire service was evidenced in their ability to engage freely with officers and firemen during and post-incident. They realised it was the men at the front, the branch operators and those supporting them, that could best describe the development of the fire and the effect of their firefighting efforts.

Some members of the Corps extended their voluntary activities to deliver lectures and demonstrations to NFS units across the nation. When the Fire Service College was established in the requisitioned Grand Ocean Hotel at Saltdean, HFO conferences were held in conjunction with senior NFS staff.

In the first twelve months of HFO activity, July 1942 to July 1943, an average of two major fires were attended by an HFO (or multiple HFOs) each week. Alongside K.433 fire reports completed by officers of the NFS, HFO reports furnished R&E with analytical scientific studies of raid fires involving food stores, flour mills, magnesium grinding factories, film stores, ships’ holds, paper mills, packing-case factories, gas works, theatres, garages, churches, ordnance stores and a tin box factory. The depth and scope of the HFOs work was to prove of inestimable value during, and after the war, and for many years beyond.

It is interesting to note that whilst the threat of high explosive bombs remained of primary interest in terms of protecting the civil population, all involved in fire research appreciated that the greatest loss of the built environment, including vital manufacturing, was affected by the proliferation of incendiary devices, with or without exploding noses. Such was the volume that the Luftwaffe were capable of dropping simultaneously that only the vaguest estimate could be made of the numbers. R&E’s ‘B’ Division (Intelligence Branch) selected defined small areas for study during raids, in which every single incendiary bomb dropped was logged, with its timing, position, distance from its neighbouring device, and effect recorded and analysed.

Camouflage, Smoke and Decoy

Although undertaken as three distinct matters, camouflage, smoke, and decoy on the home front were intrinsically connected and collaboration was mutually beneficial. In addition, the outcomes of the research were to prove of interest and benefit to the military.

Full-scale experimental work concerning camouflage of large industrial premises was largely conducted with the assistance of the Lockheed Hydraulic Brake Co., who made available their site at Leamington Spa.

Trials conducted included the use of paint on building surfaces involving the application of chippings. Others used netting in much the same manner as the military did on static positions or vehicles. In some cases, a combination of the two was trialled. When it was apparent that paint supplies in the anticipated quantity would not be available, tar and waste fuel sludge was used and far from being unpopular was found to be an improvement for camouflage purposes. Many considerations had to be overcome, not least of all the priming of non-porous surfaces such as those represented by asbestos sheeting.

The roof of the Rolls Royce factory in Derby as designed by artist Ernest Townsend to look from the air like rows of terraced housing.

Smoke-screening, which was used in an ad-hoc fashion by crews of the ORP Blyskawica during the infamous Cowes blitz of May 1942, was developed in industrial fashion under the trials and studies conducted by R&E.

The first task was to promote industrial units to increase their own smoke output for which abatement initiatives were relaxed to enable compliance. Householders were supplied with pitch and advised to burn it in their grates during raids. Seventeen householders in south-east London were temporarily recruited into the R&E testing programme, being supplied with pitch-candles they burned simultaneously to allow studies to be made. In June 1940 selected local authorities were requested by R&E to encourage all industrial works in their area to produce as much smoke as possible within the context of their normal operations, for the same study.

The true development of mass screening by smoke involved the use of chemical generators and the Haslar smoke generator – a large trailer-mounted device that featured oil burning driven by a small water-cooled petrol engine. Trials were also made at Stewartby involving the use of 1,000 modified orchard heaters. In Middlesbrough at the works of Messrs. Dorman Long and Co., a pitch-trough method was trialled. Its success after further modification to conceal emitted light was applied on a substantial scale at Derby and Crewe but didn’t come into general use elsewhere.

Through many trials and retrials, it was decided that neither the Haslar or modified orchard heaters were achieving the desired effect for civil defence purposes (although the former found use with the military). By proof of scientific analysis of the decomposition of heated or burning materials, coupled to hard earned aerial observation, at a time when both actual raids and lack of aircraft made this almost impossible, R&E settled on the recommendation that a newer development, the Greenwich mobile pitch smoke generator was the favourable option. However, so far, I have located no evidence concerning where and when this was used for real.

Modified orchard heaters being prepared and lined up ready for use in Carlton Road, Derby, 1940.

Decoy research was undertaken in relation to screening, but in such a way that not only distracted enemy bombers from real targets but tempted them to release their payloads on elaborate hoaxes.

In this endeavour R&E, having no direct authority for aviation support vital to conduct aerial observations of trials, found progress was repeatedly thwarted by the Air Ministry. For their part the Ministry had already conducted research for their own purposes, and by July 1940 were working on dummy day and dummy night aerodromes. In the same month an interdepartmental meeting between the Home Office and three service departments the Air Ministry conceded to set up a Directorate under the supervision of Colonel Sir J.F. Turner, C.B., D.S.O, for the purposes of assisting in the development of decoy (and smoke screening) for civil defence purposes).

Hand drawn map of an elaborate RAF aerodrome decoy near the village of Clearbrook, Devon.

It's intent was to distract the Luftwaffe from the actual location of RAF Harrowbeer.

The Ministry’s involvement was key, given that by August 1940 they had established 56 ‘Q’ sites (night dummy aerodromes) and 36 ‘K’ sites (day dummy aerodromes). Under co-ordination of the new Directorate the Air Ministry requested that all further experimental work on decoys, required by any of the services, was undertaken by the Ministry of Home Security; i.e. R&E.

The Ministry of Home Security was required to identify a priority list of vital points for civil decoy requirements. One of the earliest experiments of this need was the use of lights to create, by night, a reproduction of certain features of Sheffield and Chesterfield extending over a length of three miles on hills to the south-west of the former. Left in place to measure the effect, R&E recorded that it collected a number of high explosive hits (no figure provided). This provided some assurance that the cleverly poised lighting, arranged to represent dummy blast furnaces, marshalling yards, and factory lighting, had duped at least some pilots and bomb aimers.

Fire was used to simulate dummy oil tank fires. Studies of actual raids showed how pilots were prone to home in on fires on the assumption they were caused by bombs dropped by formation leaders earlier in an attack. Concrete lined circles in excavated rural ground, filled with flaming oil, proved tempting targets. Much of what was undertaken fell under the codename Starfish, and today the remains of sites are identified as Starfish sites.

In 1941, ambiguously, R&E’s involvement in this aspect of civil defence ceased. In his historical reflection Mr. Astbury states – The Mabane Committee recommended that research, experiment, and development on decoys should be carried out by the Air Ministry. With the adoption of this recommendation in September 1941, the activities of the department in this field ended.

Astbury’s explanation appears clear, until reading a contradictory copy of Ministry of Home Security minutes from the same month (held at the National Archives) that stated - In September 1941 the Camouflage Committee and the Technical Sub-Committee were disbanded following a recommendation of the Mabane Committee on Concealment and Deception that a new Camouflage Committee should be established under the control of the new Directorate of Camouflage of the Ministry of Home Security.

Whatever the fact, R&E appears to have not undertaken any further part in the deployment of decoys for civil defence.

Summary

On 28 March 1945 the air raid warning sounded in London for the last time and a day later the final flying bomb fell, 2,109 days since the first ordnance was dropped on Hoy, Orkney Islands, on 17 October 1939.

Perhaps Mr. Astbury’s manuscript was unfinished when locked away until a year before his death and received little or no attention since 1972. There is no concluding chapter, no summary of R&E’s achievements and no reference to its demise.

In May 1945, in the immediate aftermath of Victory in Europe, the Ministry of Home Security, R&E’s parent organisation, was dissolved. In a timeline of key events detailed at the beginning of his book, the last entry merely states – 1 September (1945) The Ministry of Works assumes responsibility for the work of the department.

Barely had the VE Day and VJ Day, revelry and relief subsided and an opportunity for normalcy embraced, when the world was thrown into the uncertainty of the Cold War. This unwelcome turn of events no doubt heightened rather than lessened the need for the continued work of an organisation responsible for research and experiments into civil defence. I clearly recall around the time I became a teenager, distribution of the Protect and Survive pamphlets that contained suggestions for families to create refuges in their homes, some of which differed little to the advice given to households of the 1940’s – but most of all the threat of nuclear war spread not hope and practicality, but doom and fear.

If the R&E, 1939-1945, was responsible for producing public information pamphlets during that conflict, there must have been (and in all likelihood still be) a descendant organisation. But it is hard to imagine in this modern world, with our apparent increased liberties and access to information, that any comparable organisation would so genuinely place the needs of the nation and its populace so firmly to the fore to the extent that R&E were contactable and attentive to fears expressed by the mass or the individual.

Having read Mr. Astbury’s manuscript, absorbed the complexity and scope of the work they undertook, and compared this with records and anecdotes of the effect their work had during the nations toughest trial, I have nothing but admiration for them.

Further reading

For those who wish to read Mr. Astbury's manuscript in full, there is no need to visit the National Archives. I have transcribed and represented the entire work, including all diagrams and photographs within the IWFBF range of publications available at Blurb HERE. As usual all profits are forwarded to the Firefighters Charity.

A rewarding post-script to this article is that in early June 2024 I was contacted by the grandson of Mr. A.R. Astbury who stated that he was amazed and delighted to have discovered that the book had been transcribed and made available. I gain great satisfaction from undertaking the research that contributes to this website and associated books, but there is little that pleases me more than connecting families with the activities of their forefathers.

If you have enjoyed this page, please consider making a small donation to the Firefighters Charity.